Twelve Contemporary Black and White Landscape Photography Books

This third and last of my selection of black-and-white landscape photography books focuses on contemporary work by living photographers with a strong presence in the art world, ending with artists younger than me. The books engage with the land as a dynamic space shaped by history, time, and elemental forces. They are all part of my collection and personal favorites. Not only have I thematically paired them like in the previous selection, but I have grouped the pairs to illustrate recurring motifs in contemporary landscape photography. The land may be viewed through the lens of human intervention, revealing the traces of civilization through subtle or overt marks. Some turn to the raw, elemental, untamed aspects of nature, capturing its turbulence and ephemerality, while others reduce the landscape to near abstraction, stripping away reference points to evoke a more visceral, psychological experience. This selection is quite representative of contemporary landscape photography, and even if those approaches are alien to you, there is much to be learned from studying the visual strategies at play.

What makes these works distinctly contemporary is their departure from traditional landscape photography’s conventions of clarity and beauty, which was a common thread in the previous list. Instead, they embrace fragmentation, process-based experimentation, repetition, and an awareness of photography’s role in shaping our perception of place. Whether through sequences that challenge linear storytelling, alternative photographic techniques that embed time within the image, or unusual compositions that blur the boundary between representation and abstraction, in the work of those photographers the landscape is both a physical reality and a conceptual space. They invite reconsidering how we see, inhabit, and interpret the land today.

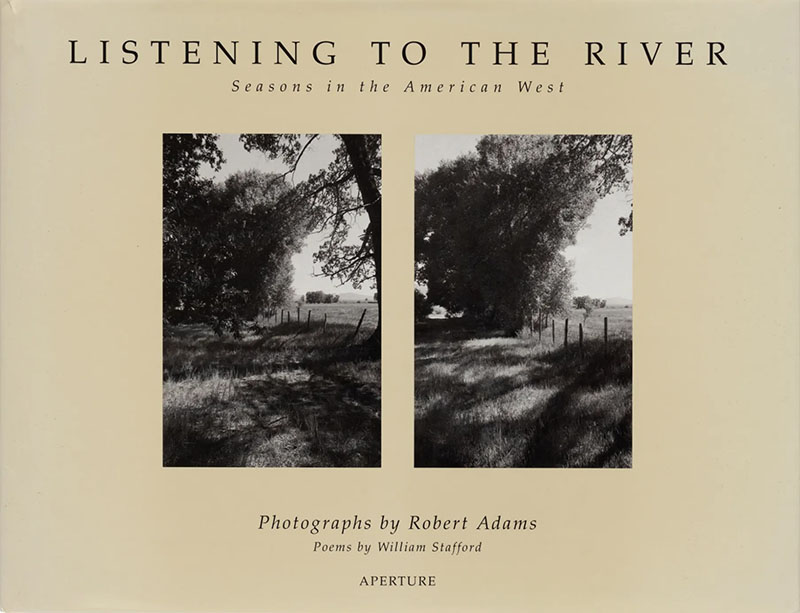

Robert Adams: Listening to the River (1994)

Robert Adams (born 1937), is influential for his unflinching and stark depictions of the evolving landscape of the American West, revealing both its beauty and the impact of human encroachment. Of the ten photographers in the “New Topographics” exhibit which could be argued to be the starting point of contemporary landscape photography, he is the most sensitive to the natural world. Some of his most influential books such as The New West depict developments, but Listening to the River takes place in the anonymous, workday landscapes of the American West, conveying a sense of place through straightforward and unembellished images of rural environments. The book is distinguished by its innovative use of sequences from two to seven images on each spread following multiple strategies. They create a sense of being around and moving in the landscape through a contemplative journey that explores with a poetic sensibility the fragile balance between nature and human presence.

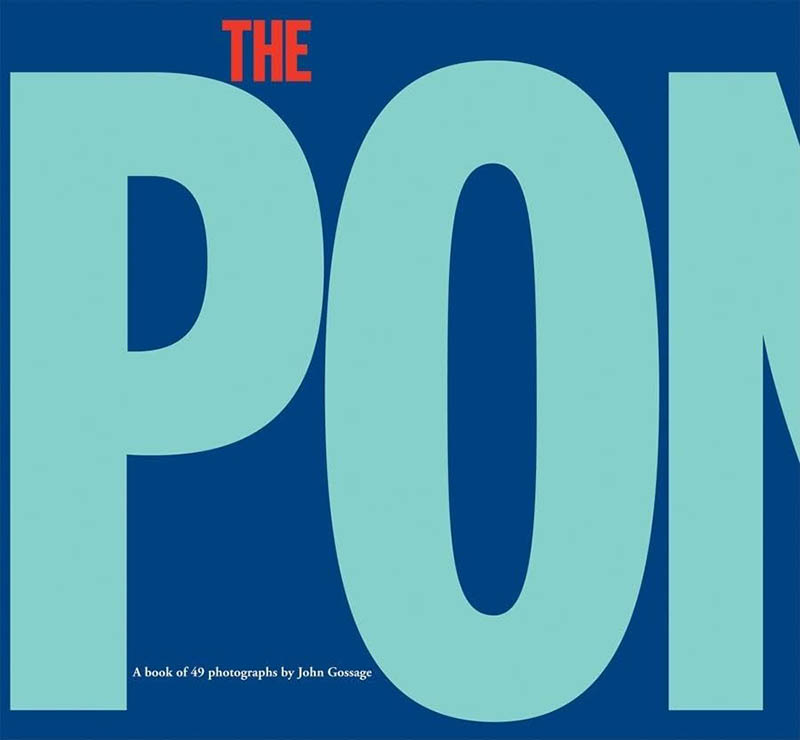

John Gossage: The Pond (2010 reprint)

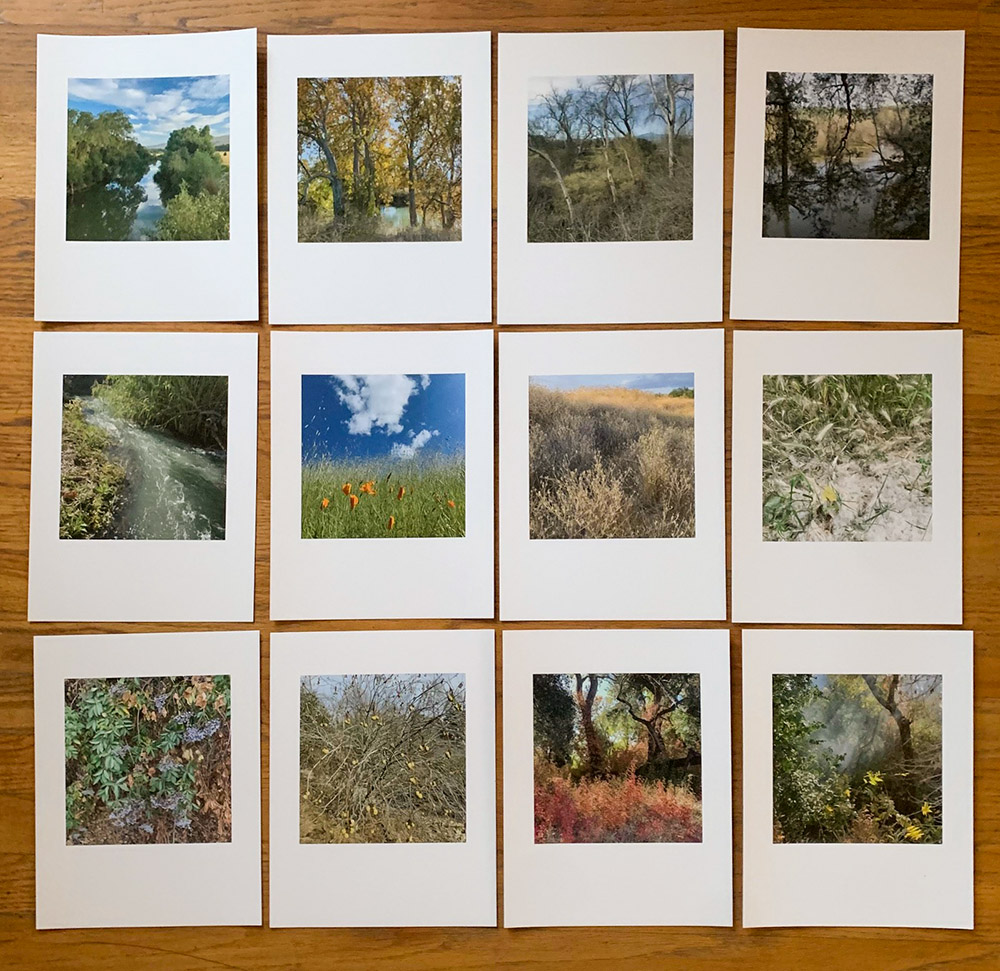

John Gossage (born 1946) explores the urban and suburban landscape in subtle and psychologically charged photographs that reveal their overlooked and ambiguous aspects. Although a prolific bookmaker with over thirty publications, it is his second monograph that became one of the most seminal and groundbreaking books in photographic literature, even though Gossage stated that in 1985, they couldn’t give the book away. Nowadays it is trendy for photobooks not to have a photograph on their cover, that was groundbreaking then – the reprint reverses the colors. The Pond chronicles a walk to and away from a pond in an unremarkable stretch of land at the interface of the city and the country, a then-new territory many have explored since – and has become my most recent focus. There is a fondness for the natural world as a place of redemption or loss. Yet, the images stay away from celebrating beauty. Instead, they experiment with photographic seeing, maintaining an ambiguous tone that leaves interpretation to the viewer, yet another hallmark of contemporary photography.

Mark Klett: Revealing Territory (1992)

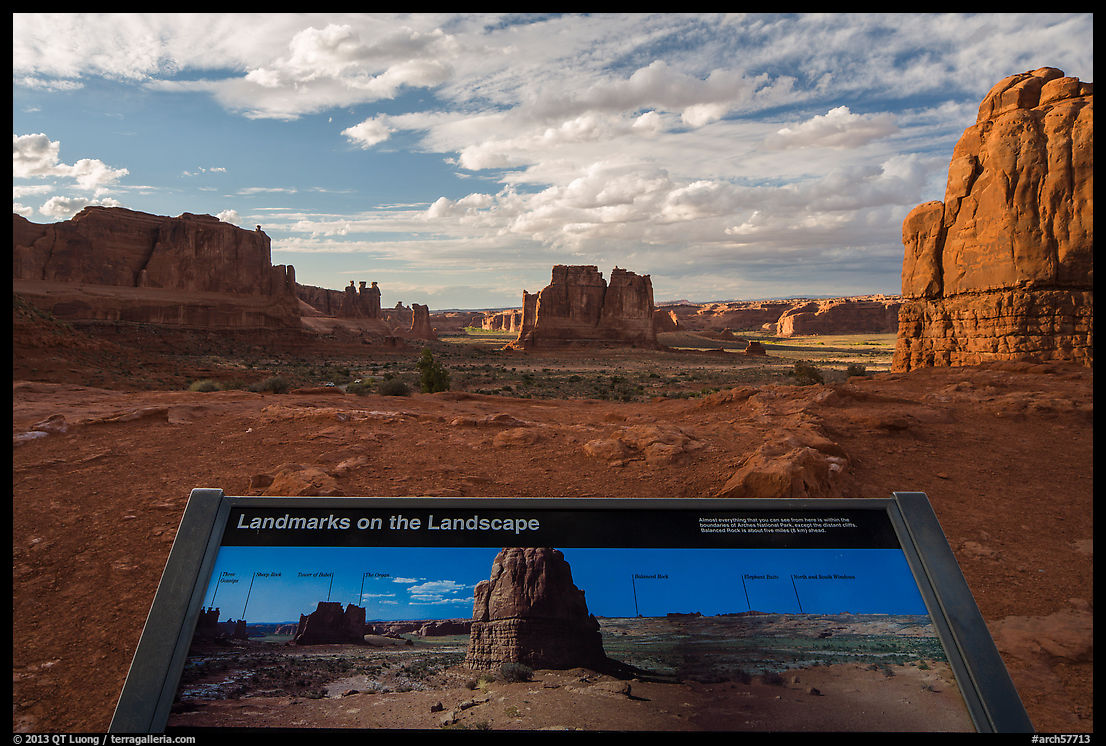

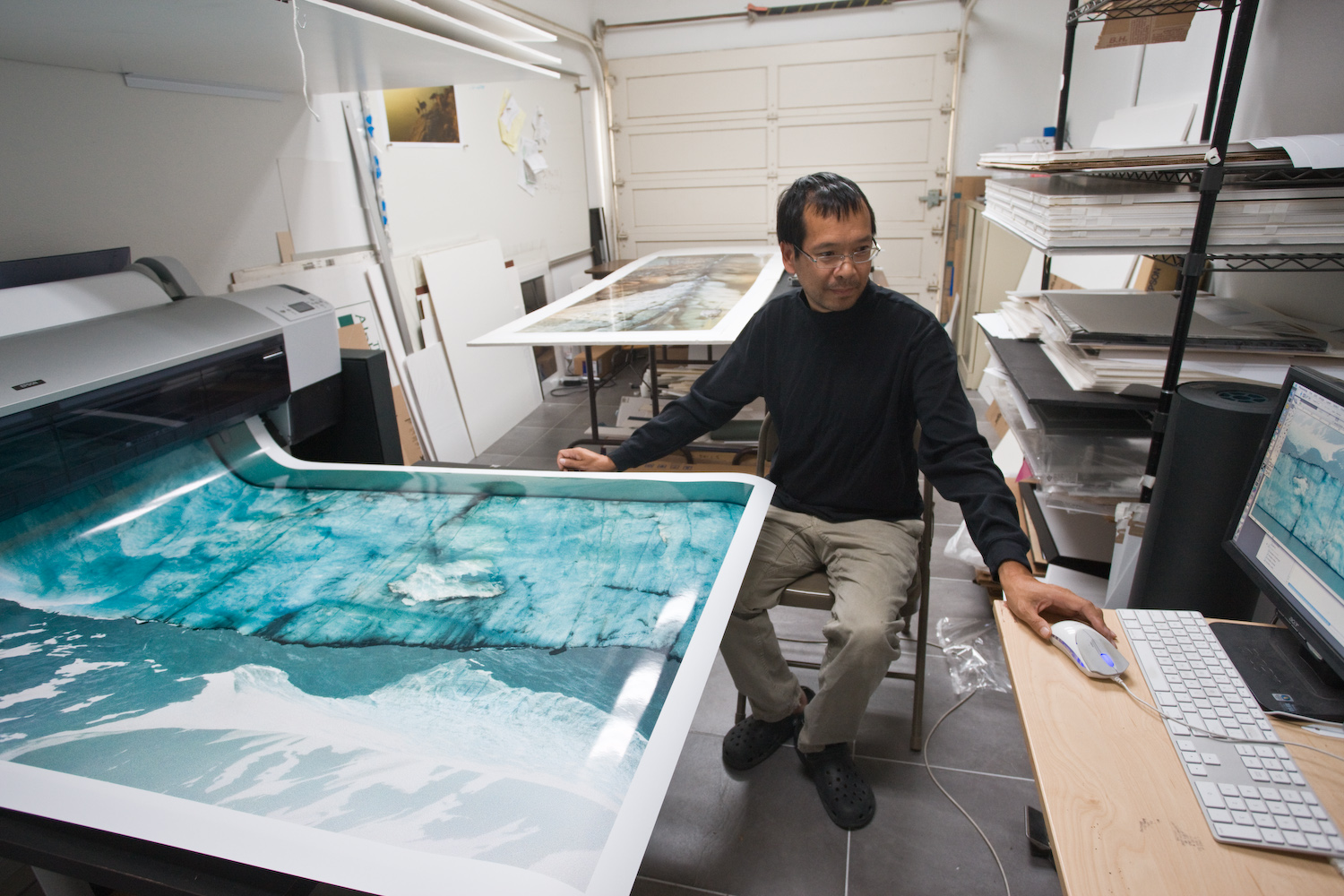

Mark Klett (born 1952) explores time and history through conceptual landscape photographs of the American West. He is mostly known for his pioneering contributions to rephotography – the practice of creating a contemporary image that perfectly aligns with a historical image – and for extensions to the methodology. My favorite of his several rephotography books is Yosemite in Time (2005). Besides the dialog with significant images from past photographic giants and the connection established between them, the rigorous technique yields insights into environmental changes. However, the book does not fit this list because some photographs use color. Instead, in the more personal Revealing Territory, Klett uses 4×5 Polaroid Type 55 film (also one of my favorites until it was discontinued in the early 2000s) and embraces the materiality of that process through its edge markings and the addition of handwritten captions to the prints. This approach lends the images a sense of immediacy and direct engagement with the landscape, blurring the line between photography as documentation and as an artifact of experience. The book presents a multifaceted portrait of the Western landscape, incorporating images that range from expansive desert vistas to human interventions, underscoring Klett’s interest in the evidence people have left of their experience of the land.

Mark Ruwedel – Westward the Course of Empire (2008)

Mark Ruwedel (born 1954) blends historical inquiry with contemporary concerns about land use in America. Based on extensive research, Westward the Course of Empire traces the remnants of abandoned railroad lines that once symbolized the expansionist ambitions of the 19th century. The book is a typology of these forgotten paths through the land, revealing the scars left by human industry and the slow reclamation of the land. Ruwedel’s restrained, methodical compositions and rich black-and-white tonality underscore the transience of human endeavor, making this a powerful meditation on history, landscape, and the passage of time.

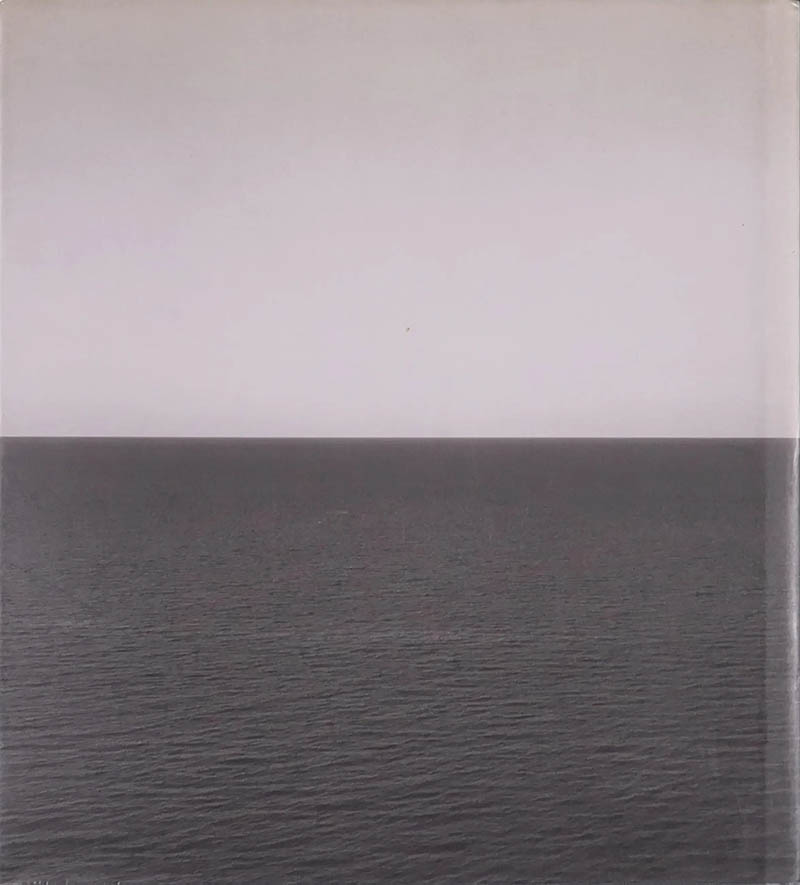

Hiroshi Sugimoto – Seascapes (2015) (*)

Hiroshi Sugimoto (born 1948) is one of the most important conceptual photographers of our time. Photographed on an 8×10 camera like his other projects, Seascapes may be his most radical project, as it presents an austere and profound vision of the ocean that pushes minimalism to its extreme. Each image follows the same compositional structure, dividing the frame equally between sea and sky. The world is reduced to a simple horizon, excluding other elements such as clouds or rocks, and long exposures dissolve surface detail, transforming waves into ethereal, time-suspended expanses. The repetition and subtle variation in atmospheric conditions and light evoke a sense of eternity and stillness, as the scenes could have been witnessed by the earliest humans. (*) Photographed over several decades at locations around the world, Seascapes comprises over 200 photographs. When the book was published, I thought it was too many and passed. The book sold out and became prohibitively expensive, so I had to content myself with a catalog presenting a representative sample of the series among others, the 400-page Hiroshi Sugimoto (2010). The cover is pictured above, and it differs only slightly from the cover of Seascapes. That book is itself out of print, but the recent and shorter Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine (2023) by the same publisher is readily available.

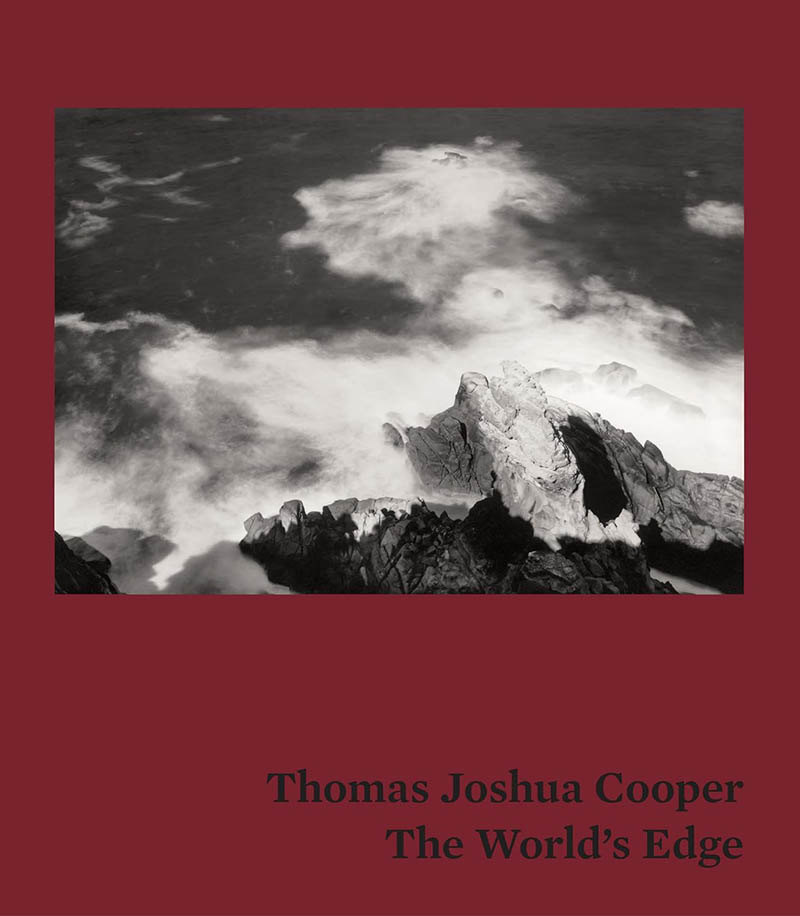

Thomas Joshua Cooper: The World’s Edge (2019)

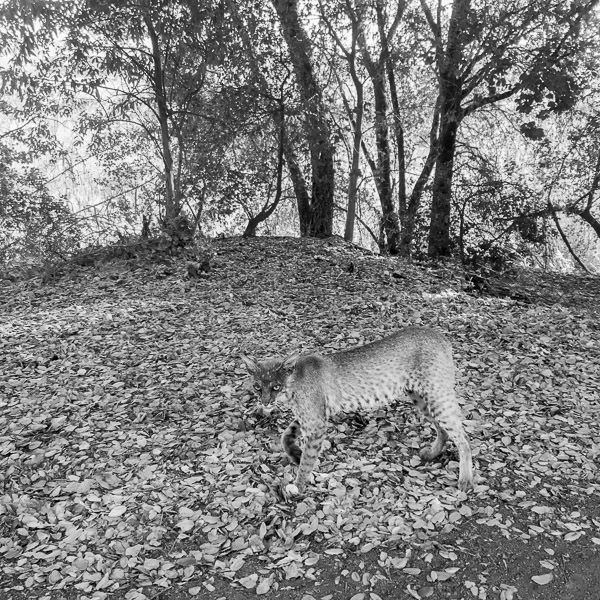

Thomas Joshua Cooper (born 1946) opus magnum project maps the limits of human exploration through images photographed on six continents over a quarter-century. Using exclusively a 5×7 Agfa Ansco camera made in 1898, Cooper makes only one exposure per place. His work, often created under extreme conditions and through extended expeditions to remote places, captures coastal edges and historical waypoints. Although they are about human exploration, mythology, and history, they are devoid of any human traces. Long exposures and abstract compositions generally excluding the horizon transform seascapes and landscapes into mythical spaces of emptiness. A pitch-black photograph taken at the South Pole on winter solstice contrasts with a whiteout near the North Pole. The sequencing follows a journey, leading the viewer through an atlas of seascapes that act as timeless, metaphysical places.

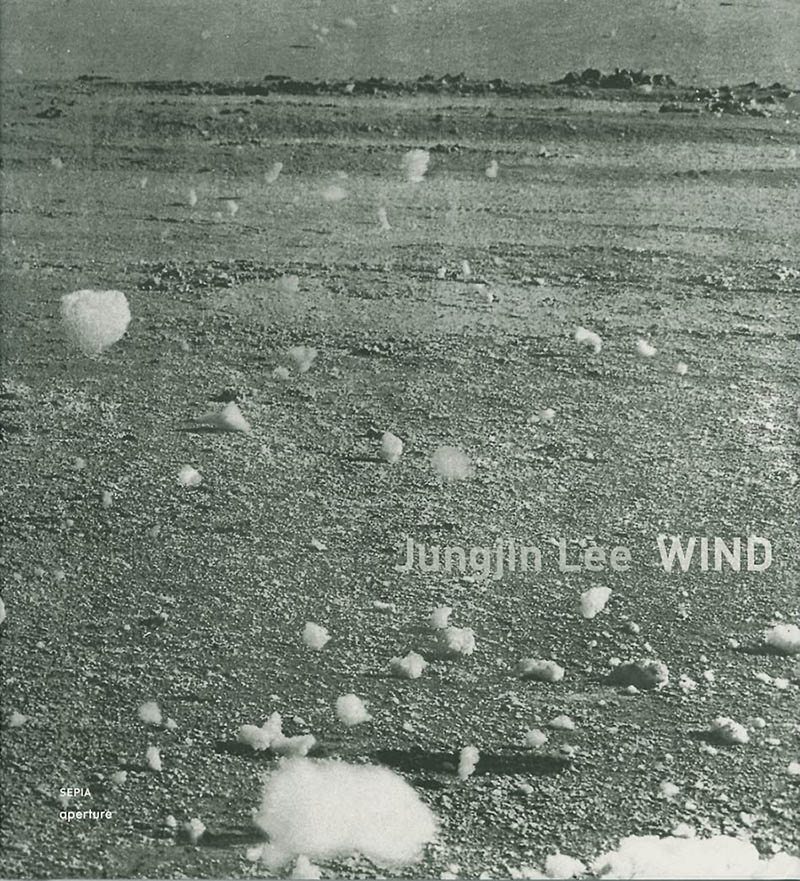

Jungjin Lee: Wind (2009)

Jungjin Lee (born 1961) fuses Eastern aesthetics and Western landscape traditions, creating textural and graphic images that transcend documentary representation, even when made in well-trodden nature locations. Wind, maybe her best-known book, studies one of the elemental forces that shape the land, capturing the movement of air, sand, and light in vast, open spaces. Printed on handmade and hand-coated paper, the images take on a textured, tactile, painterly quality, reinforcing their ephemeral yet grounded presence. The book’s sequence flows like shifting currents, immersing the viewer in an environment that feels both ancient and impermanent, emphasizing the dreamlike dimensions of the landscape.

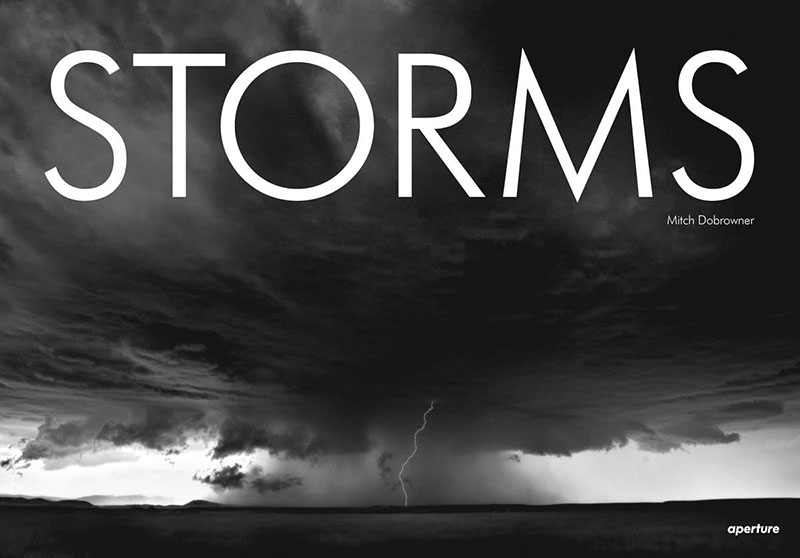

Mitch Dobrowner – Storms (2013)

Mitch Dobrowner (born 1956) pushes Ansel Adams’s esthetics further, creating eloquently dramatic black-and-white landscape images using digital photography. Storms is about the skies, capturing the raw power and sublime beauty of nature’s most volatile moments. Bringing fine-art photography esthetic to storm chasing, the book presents a series of monumental, highly detailed photographs of supercells, tornadoes, and other severe weather phenomena, emphasizing their sculptural, almost supernatural presence. The sequencing builds tension, moving from distant formations to explosive moments of energy and destruction. Dobrowner’s precise compositions and deep tonal contrasts highlight the delicate balance between chaos and order, offering a cinematic portrayal of nature’s elemental forces.

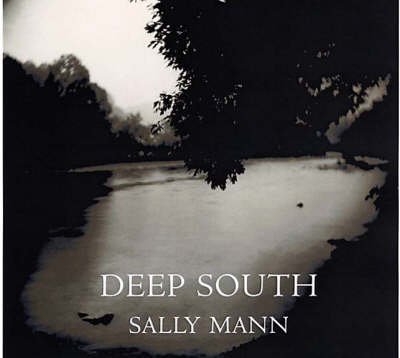

Sally Mann – Deep South (2008)

Sally Mann (born 1951) has photographed in the American South since the 1970s with large-format cameras, exploring themes of memory and the deep resonance of place. Although she came to prominence with her silver-gelatin intimate portraits of her family, she subsequently turned to evocative and romantic landscape work using antique processes. Deep South is a poetic and atmospheric meditation on the landscapes of the American South, infused with a sense of loss and historical weight. Using a wet-plate collodion process that introduces imperfections and a quality that almost seems like a hybrid of photography, painting, and sculpture, Mann renders the landscape as tangible and spectral. The book’s elegiac tone invites viewers to experience the landscape as a site of memory, where past and present remain inextricably intertwined.

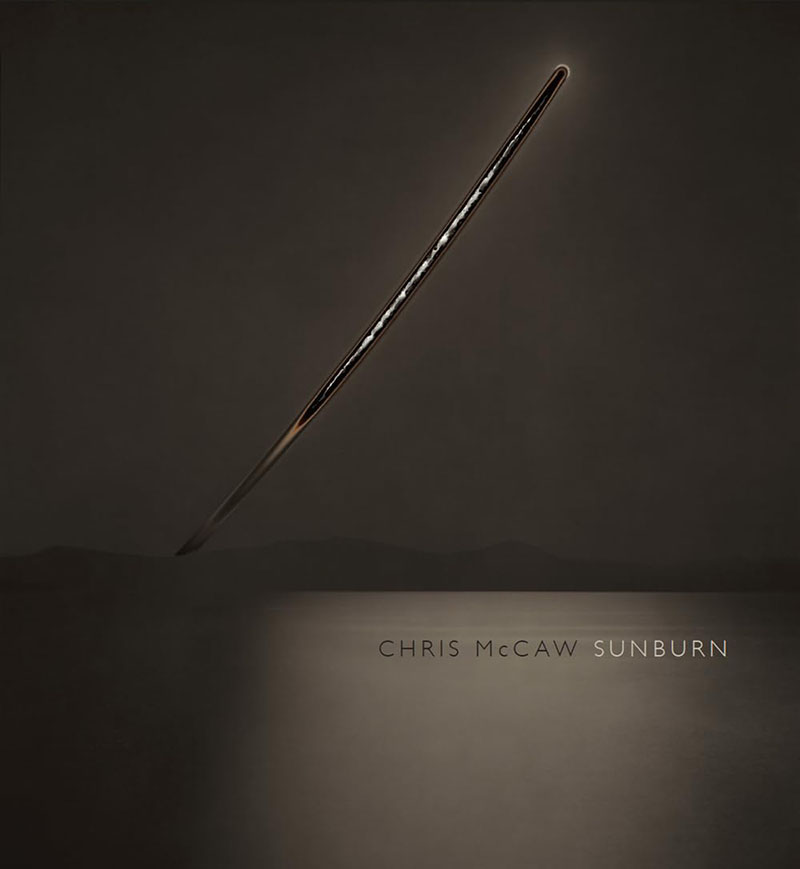

Chris McCaw – Sunburn (2012)

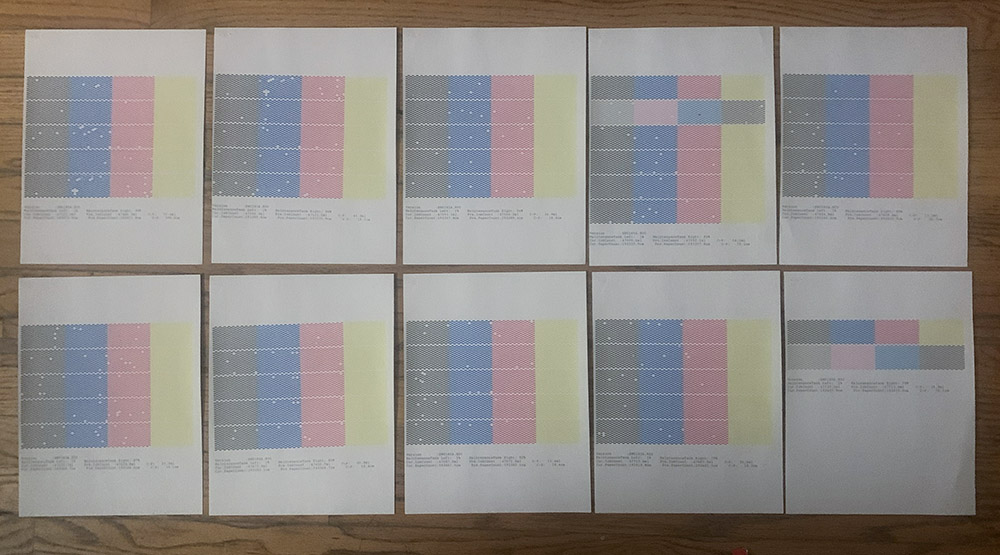

Chris McCaw (born 1971) is known for his unique process refined over time, in which he directly exposes photographic paper to the sun in hand-built ultra-large format cameras. The intense exposures, often taking hours or even days, result in an inversion of tonalities aptly called solarization, giving the images a unique, almost abstract quality. Sunburn, which represents the foundation of his imaginative subsequent work with the sun, captures the passage of time in a literal sense: the sun’s rays etch themselves into the emulsion while smoke comes out of the camera with a faint smell of roasted marshmallows as the gelatin of the paper is burned. The charred, sculptural, one-of-a-kind prints emphasize the raw interaction between photography and nature.

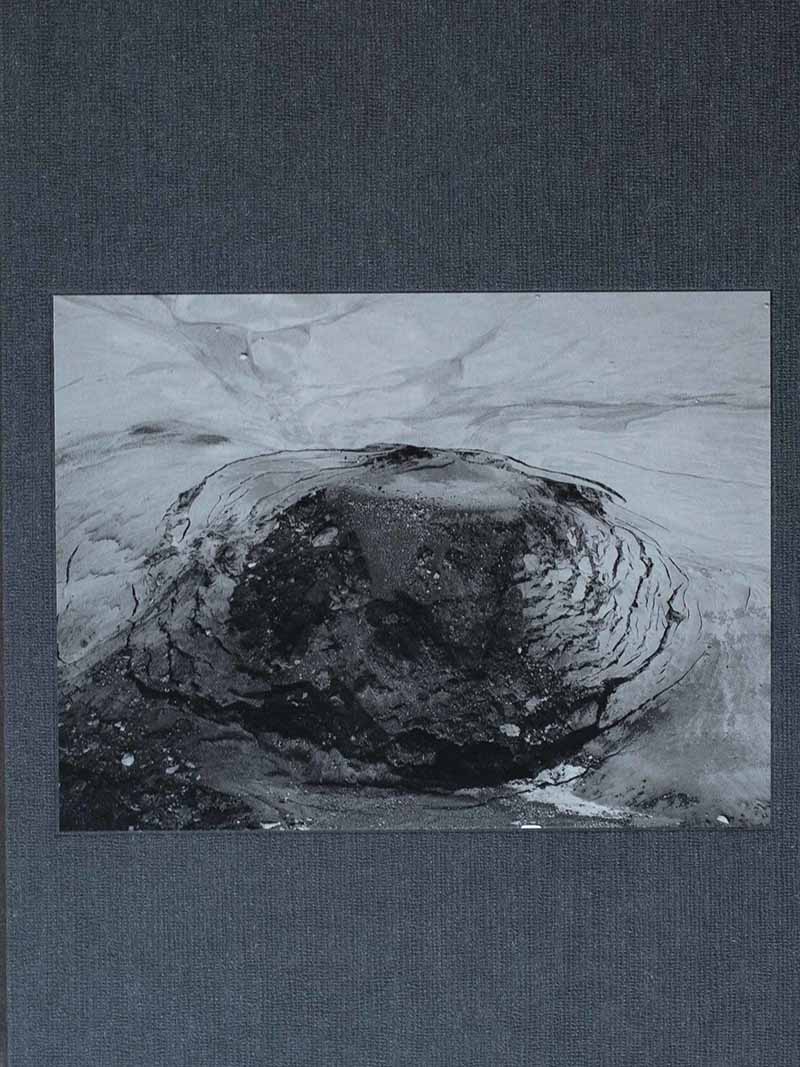

Ron Jude – 12 Hz (2020)

Ron Jude (born 1965) explores themes of memory, identity, and place through understated, conceptual photographs. 12 Hz departs from his previous color work where the landscape is a storytelling component, and also from the West Coast landscape photography tradition. Presenting a dark, primordial vision of the Earth, Jude digitally captures highly detailed and often claustrophobic, abstract images of rock formations, turbulent waters, and geological remnants that exist beyond human time scales. Those images almost entirely devoid of life are contrasted with equally claustrophobic chaotic forest floors printed on thiner paper. The book’s title references ultra-low frequency vibrations associated with seismic activity, reinforcing its focus on landscapes shaped by forces beyond perception, where human presence is insignificant.

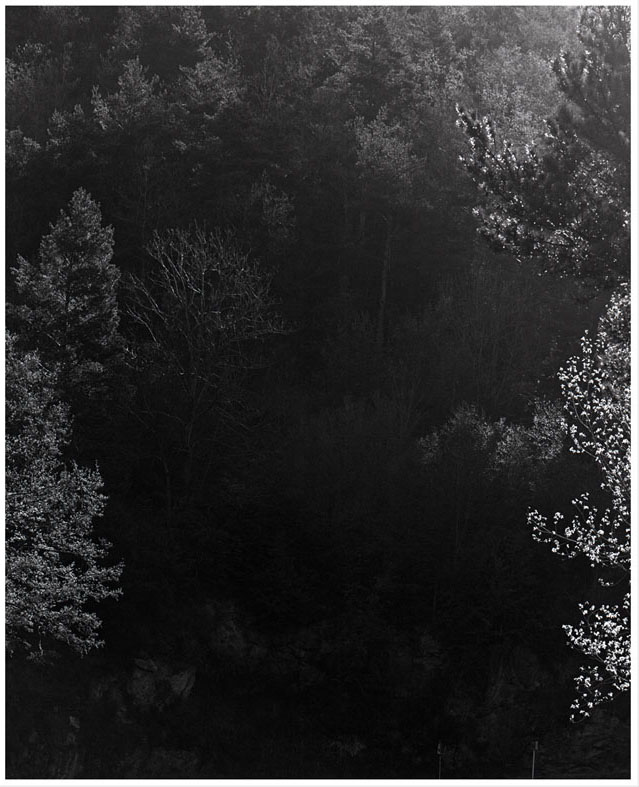

Awoiska van der Molen – Sequester (2014)

Awoiska van der Molen (born 1972) is a rare contemporary photographer whose practice until recently was only in the natural world. Her monumental and often dark and abstract silver-gelatin landscape prints are intensely psychological, conveying solitude, silence, and an emotional connection to the land. Although photographed entirely in the Canary Islands during solitary sessions, Sequester is not about place. The image titles, consisting of only numbers, have no place names in them. The book is about mood and being there. Composition is less important than the alternance of light and shade. The images, made with long exposures in low light, presented one of the greatest challenges to reproduce in a book. They are black-and-white photographs with varying degrees of abstraction, often erasing any sense of the physical scale in front of the camera. Many feature a limited tonal range, from the deepest blacks to dark grays. The designer, Hans Gremmen, has done a brilliant job in translating the work within the constraints of a book, alternating regular pages printed on white paper with black pages onto which sections of the images are printed in full bleed with silver ink. This creates a striking, immersive experience faithful to a work defined by introspection that goes beyond mere representation to emphasize emotions and feelings.