Autumn in New England

No Comments

https://www.terragalleria.com/blog/autumn-in-new-england

The first time I had flown somewhere just for the purpose of photography was when I traveled to New England in the fall of 1996. Beyond the pastoral scenes, the revelation of the fall foliage there turned out to be the starting point for my updated approaches to time and scale.

Back then, since arriving in California three years earlier, my photography had been limited to wilderness areas like national parks, and occasionally cities like San Francisco. The rural landscape in the Golden State is often dominated by industrial agriculture. Even family farms lack harmony with the land which I remember from the French countryside. Small towns are usually just scaled-down versions of larger modern towns. Before my 1996 autumn trip, I had been in Boston to visit MIT. Although I had noted its similarities with European cities, I had not set foot in the countryside of New England. Unlike in the West, many of the structures in rural Vermont date back to the 17th century. The countryside offered that cozy feeling of a long lived-in landscape. Villages nestled in valleys surrounded immaculate white steepled churches. Centuries-old farms and red barns dotted rolling hills and meadows. It was a perfectly picturesque pastoral landscape.

The locations I visited offered perfect compositions of rural New England scenes because I relied on a photography guidebook that listed 23 iconic “photo scenics” selected for that reason. Yet, I seldom encountered other photographers at those well-known locations, except for one early morning at the Jenne Farm. Seeing a dozen tripods was unusual enough to compel me to take several pictures of their lineup. As far as I can tell, the photographers were respectful, staying at a distance from the farm and close to the road. In recent years, social media has brought so many unruly visitors to Jenne Farm – some of them breaking into buildings to use restrooms – that the entire area had to be closed to non-residents during October. Authored by local photographer Arnold Kaplan, the modest self-published, 72-page stapled booklet did not include any photographs. Instead, it featured hand-drawn maps of each site with recommended tripod locations marked. Some may shun such an approach, but at that time it felt right for me, as I viewed myself as a travel photographer. For many years I continued to use guidebooks in new locations when looking for travel images. I found value in having a pre-selected list of places that have proved productive for others, knowing that once I am there, I am free to look for my compositions before comparing them with a reference, an instructive exercise.

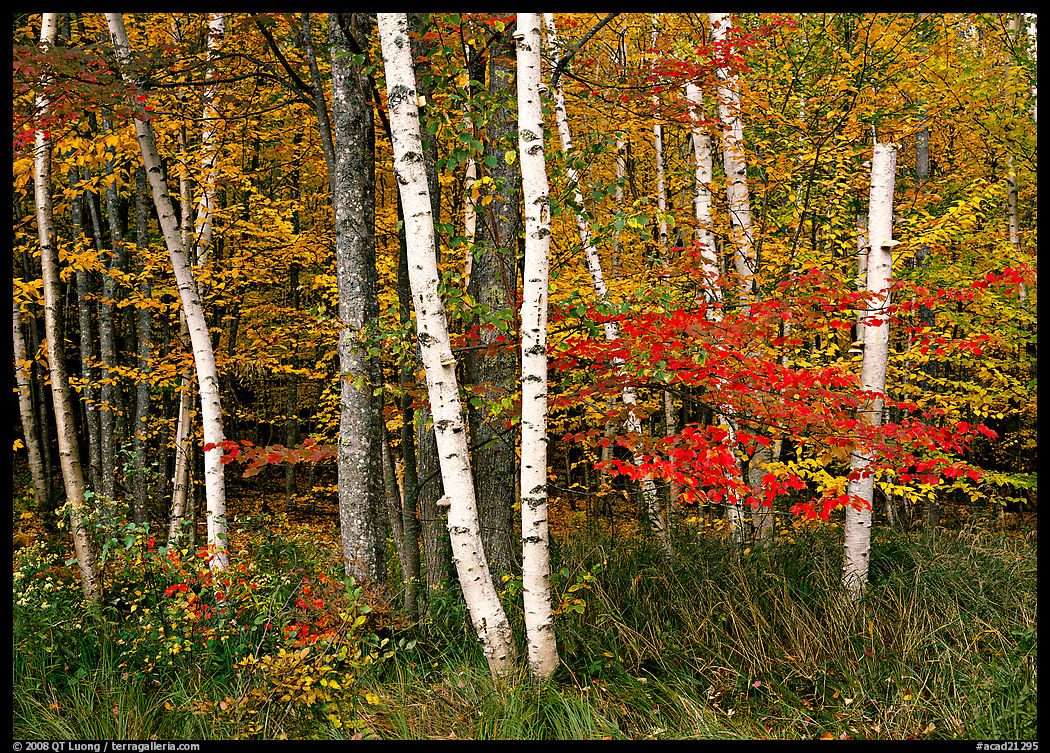

The main motivation for my trip was to check out the renowned New England fall foliage. In most places in the U.S. West, the main contributors to fall color are aspens, cottonwoods, or oak trees. When autumn arrives, the color turns to various shades of yellow. The East’s plentiful maple trees add brilliant hues of oranges and reds, transforming the landscape into a vibrant palette of color if you are there at the right time. Nowadays, many websites track the progression of fall color. Still, finding the perfect window is not easy since conditions can vary from valley to valley and changes can occur overnight. For instance, between the two mornings I visited Jenne Farm, the change in foliage had progressed noticeably. With my usual luck, the best light and foliage did not coincide. The peak of fall color in Vermont can occur anytime between late September and mid-October, depending on the year. However, before the peak the abundance of greens provides some additional color contrast, whereas after the peak clusters of colored leaves no longer obscure the arboreal structures of the trunks and branches, enlivening their stark beauty.

I was astonished by the New England fall foliage. It was unlike anything I had seen before. Combine that with the attraction of fewer visitors, cooler temperatures, more dynamic weather, and reasonable daylight lengths, and you can see how I became so fond of autumn. I made a goal to visit each of the national parks during that season (see guide to fall foliage in the national parks). The power of the fall foliage displays in New England is such that it forced me to feel wonderment about the changes in nature. Since then, even when standing in places where that change is much more subtle, I have learned to experience some of that wonder by looking carefully. This appreciation of change is why I planned my national park travels the way I did, with several shorter visits rather than one extended stay. One single long visit is more relaxing, logistically easier, and reduces the environmental impact. However, multiple visits make it possible to see the parks in different seasons and with more variation in weather. In hindsight, the richer observations and experiences made the compromise worth it.

I had long admired the photography of Eliot Porter (see my survey of his books). In 1991, Nature’s Chaos was the first nature photography book I bought. Porter coined the expression “intimate landscapes” and his artistic practice is almost entirely focused on them. However, it is the awe-inspiring power of mountains that inspired me to start photography. In the West, as I found plenty of spectacular scenery all new to me, my first instinct was to convey a sense of their sublimity. On this New England trip, when it came time to turn the lens towards the natural world instead of depicting man’s imprint in pastoral scenes, I quickly grasped that the eroded mountains were no match for the Sierra Nevada. On the other hand, the intricate beauty of fall foliage was new to me. I realized that more intimate compositions may be better at conveying their beauty. I started to look for smaller scenes instead of grand landscapes. Photographers like Porter, John Wawrzonek, and William Neill made their photography look effortless. However, upon trying my hand at it, I realized that finding a great composition of something as simple as tree trunks with harmonious foliage is not as easy as it seems. Such scenes may appear routine, but it takes a lot of looking to discover a satisfying photograph. Working in large format, I shot sparely out of necessity. At the beginning of the trip, it was common not to find a single nature photograph during an entire day. However, by the end, my vision for those had improved.

It probably helped that I finished my trip in Acadia National Park because due to the coastal influence and elevation, the fall foliage peaks later there than in the mountains of Vermont and New Hampshire. Being in a national park surrounds you with pristine – or pristine-looking – nature removed from the distractions of human development. Their power is that being there is enough for us to feel wonder. With efforts solely directed towards nature scenes, I made progress. Being used to the expansive scenery of the West, I was surprised to find that Acadia National Park packed such a great variety of scenery into such a small and easily accessible area: woods, coastline, lakes, and mountains. A significant extension of the National Park system in 1919, Acadia National Park was the first national park established in the East for a good reason: it is the crown jewel of the East Coast. I was lucky it was also the first national park I visited outside the West. The visit served to highlight the diversity of the parks and to reinforce my determination to photograph all of them, but now paying more attention to seasons and smaller scenes.