Grand Staircase Escalante Ends

Just like in Treasured Lands, for my new national monuments book one of my goals was to cover each of the monument’s corners, providing photographs and information about each of its significant areas. I had visited Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument multiple times before, but the monument is so vast that there were still two areas demanding my attention. Located respectively at the Northeast end and Southwest end of the monument, they include canyons of diverse sizes.

The Burr Trail – with a UT-12 intermission

Although my 180-mile route from Bears Ears National Monument to Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument via UT-95, UT-24, and UT-12 traversed some of the most stunning terrain in the Southwest, I contented myself with enjoying the scenery from behind the windshield, as I was planning to arrive early enough in Long Canyon to photograph.The Burr Trail is a backcountry road starting from the town of Boulder and featuring remarkable domes and cliffs on its way to the wild southern section of Capitol Reef National Park. Its first 31 miles, up to the national park boundary, were paved in the 1990s, significantly increasing the area’s visitation. I had driven the Burr Trail before on my way to Capitol Reef National Park but as I prioritized destinations like Strike Valley Overlook and Halls Creek Overlook, I did not make much effort to photograph along the Burr Trail. Midway between Boulder and Capitol Reef National Park, the Burr Trail follows the bottom of aptly named Long Canyon for 7 miles. When I got there, the sun already quite low on the horizon did not create any reflected light in the canyon. After driving back and forth, I settled for a view of the canyon from the road at the point before it drops. The soft light occurring after sunset worked well for such a view from above. Afterward, it was too dark in the canyon.

I drove back to the Deer Creek Campground. The small campground (7 sites), tucked into a delightful riparian area would be cozy place to relax, enjoying the luxury of the picnic table, but the next day I woke up again an hour before sunrise. I thought that it would be more productive to spend sunrise time on UT-12 at overlooks over open terrain, rather than in Long Canyon. Although Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument is vast, most of it is roadless. UT-12, or Scenic Byway 12 is one of the most spectacular roads in America. My favorite section is between Escalante and Boulder, where it stays almost entirely inside the monument and traverses colorful slickrock terrain, giving an excellent introduction to the monument. I photographed from the Head of the Rocks Overlook, about half an hour drive from the campground, in pre-dawn light. On the way, I had noticed a pullout from the Hogback Ridge, a stretch of UT-12 with precipitous drops on both sides, but it was pretty dark and I was engrossed in an audiobook, so I did not stop. It was a mistake to let myself be distracted. I realized that it would have been preferable to switch those two locations, or even better to head there last evening instead of Long Canyon. The canyons would have benefited from the pre-dawn light, similar to the Long Canyon image above, while direct light would have worked at Head of the Rocks right after sunrise. However, right after sunrise, the canyons were shaded by the Hogback Ridge, with the light actually improving as the sun rose.

Back to Long Canyon, I strolled into a small side canyon on the north side of the road, slightly more than a mile from the southwestern end of the canyon. Called Singing Canyon because of its acoustics, this slot canyon is enlivened by photogenic trees and a beautiful glow from reflected light in mid-morning. As the sun reached the canyon, although I had expected the contrast to become problematic, I was able to use the play of light and shadow for images of different character. Don’t assume that a certain type of light will be “better”!

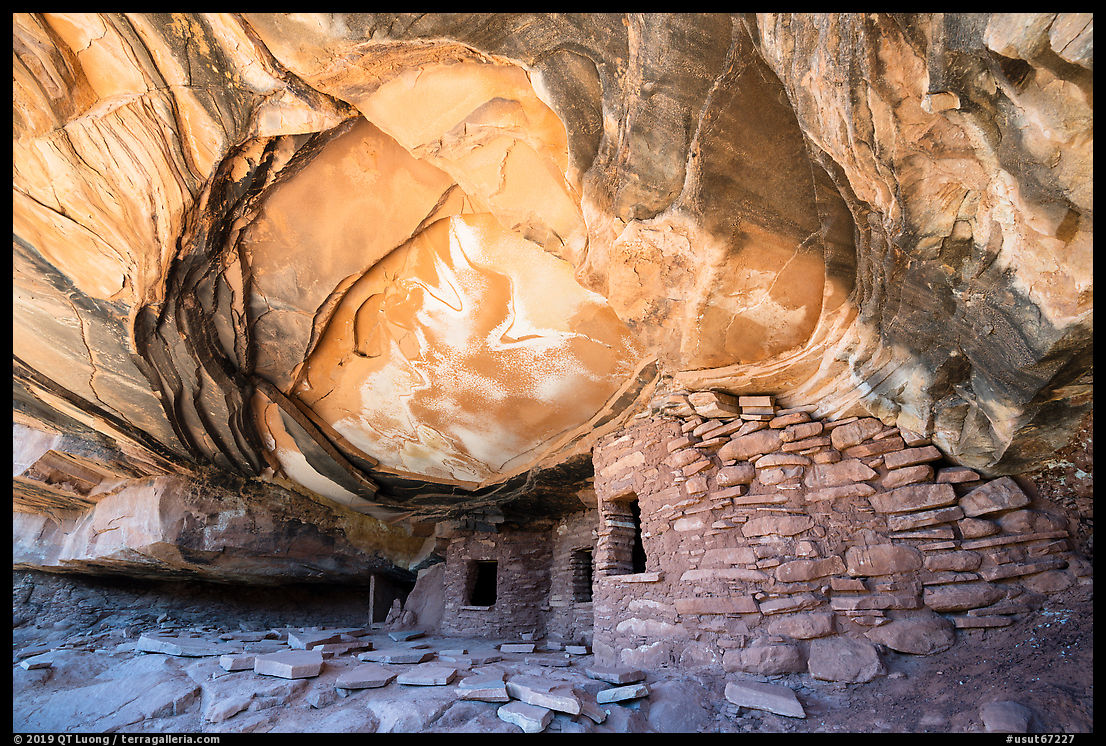

The sheer red walls of Long Canyon are graced with desert varnish and unusual erosion patterns, best photographed in the shade with reflected light. As I exited the canyon to the east, the red cliffs turn multicolored like those of the distant Waterpocket Fold, with a saddle at the rim of the Circle Cliffs providing an excellent viewpoint over badlands, plains, and cliffs.

Skutumpah Road

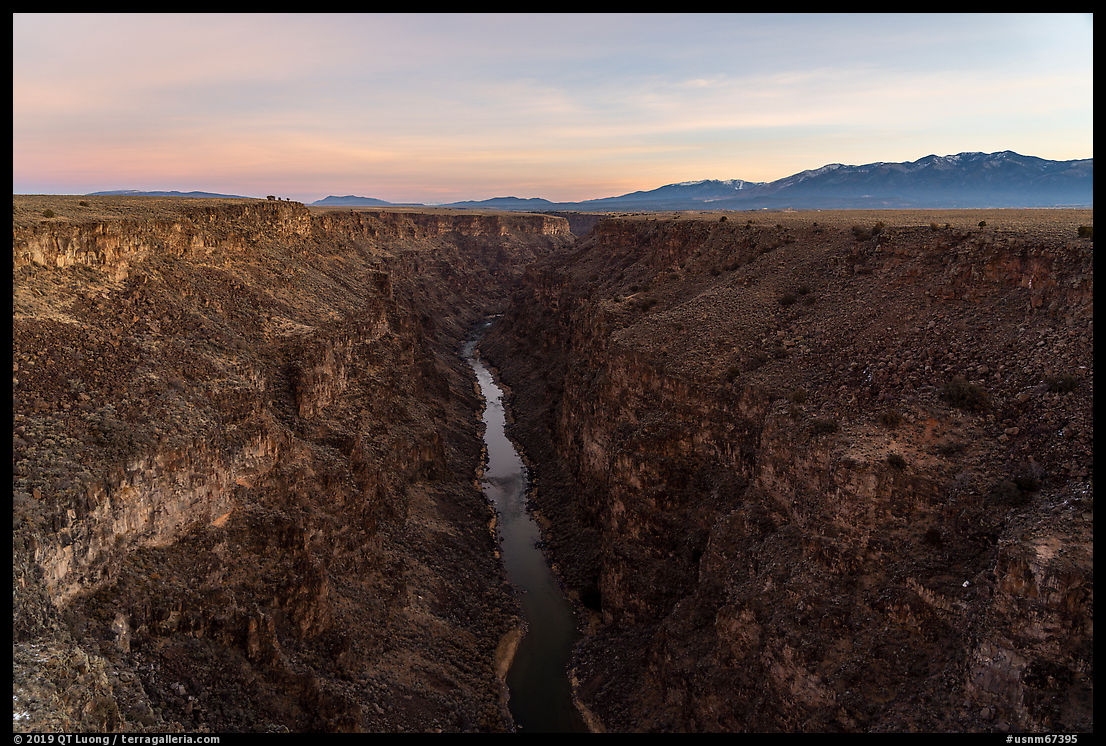

Near the west edge of the monument, Skutumpah Road, continuing south as Johnson Canyon Road for a total of 46-miles provides an alternative to Cottonwood Canyon Road for crossing the monument from north to south. The clay road is generally well maintained, but a few short rough sections are best navigated with a high clearance vehicle. Although it traverses unspectacular wooded hills and valleys, Skutumpah Road provides access to interesting canyons. The most accessible of them is Willis Creek, 6.3 miles from the north end of the road. Its narrows starting just a quarter-mile from the trailhead are distinguished by a year-round stream and curving walls. It was also interesting to look out of the narrows and see pine trees. Although I had explored several slot canyons in the monument, I had not seen those characteristics before.

Shortly after the junction with Skutumpah Road, Johnson Canyon Road enters a 4-mile section of white slickrock walls where the scenery improved considerably. After photographing them at the edge of the light, I almost hit a deer in the dark. As I applied brakes, the snack bags on the passenger seat spilled. Since it was still early in the evening, I made a detour into Kanab. I bought fresh fruit, bread, juice, and chips at the supermarket. Since I was in town, I ordered a pizza to go, and while I was waiting, I cleaned up the spilled food in the car. The pizza would save me cooking time, since I could eat it while driving to the White House Campground. The campground – one of only three developed campgrounds in a parkland of nearly 1.9 million acres – was part of lands removed from Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument. On that day, I had driven almost 250 miles, while circling around half of Grand Staircase Escalante, a good indication of the size of the monument. I was looking forward to leaving my car parked for the next day.

The Last Road Trip: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 to be continued