Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument: Maine’s Newly Preserved Backwoods

Logistics

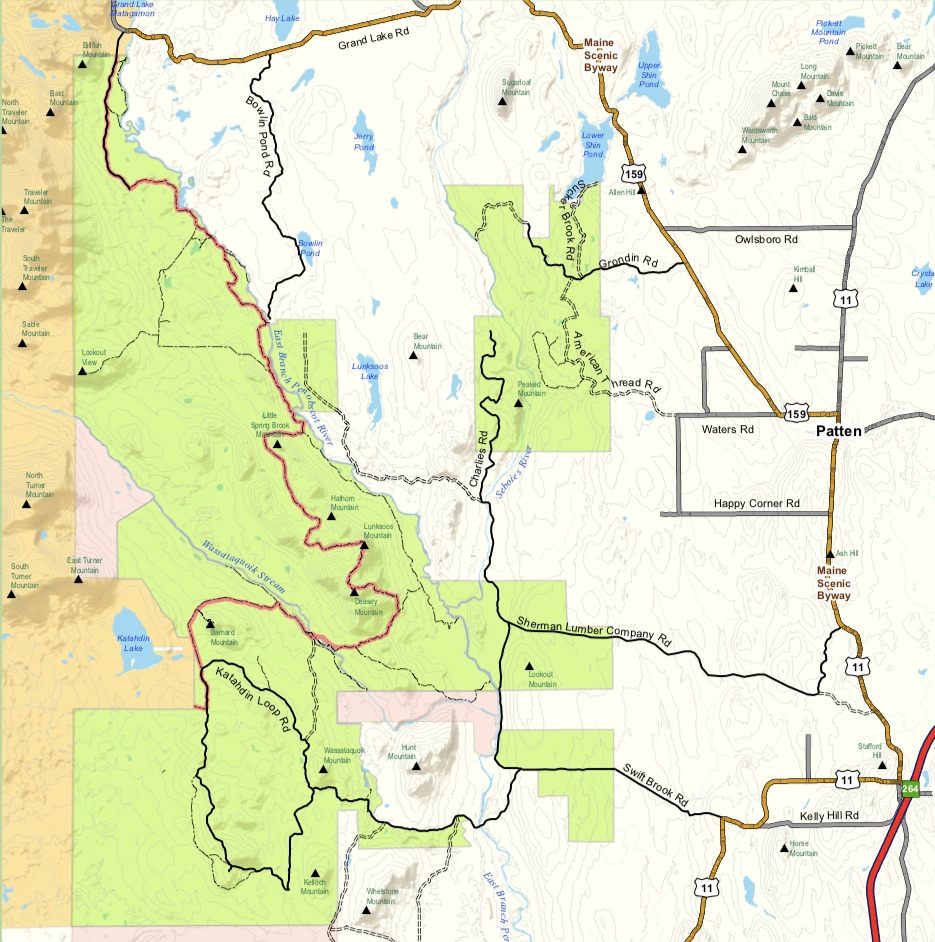

Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, located in Maine, borders the august Baxter State Park to the east. I flew to the convenient airport – only “international” by name – of the closest city, Bangor. Since no roads in the monument are paved, I rented a compact SUV. It occurred later that with careful driving, those former logging roads would have been passable with a regular passenger car. There are no services in the monument, and the closest town with amenities being Patten, 45 minutes away from it, I took advantage of the midnight closing time of Bangor’s Walmart to stock up on groceries, a butane canister for my stove, and plenty of water. Driving to the Lunksoos Campground took 1h30, and I arrived at 2 am after a full day of travel that started in San Jose at 5:30 am. With hardly any signage until the monument’s border, and little cellular service within the monument, good directions are essential. I used an assortment of maps from NPS and Friends of Katahdin Woods and Waters and set my navigation app for the intersection of Seboies Rd and Swift Brook Rd in Patten.(click on map for more details)

Besides the omnipresent woods, Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument main features are its rivers (most notably the East Branch of the Penobscot River) and a chain of 1,500–2,000-foot peaks in the eastern Katahdin foothills. There are a few small detached units, but since they are open to hunting, I thought October was not the best time to hike there. The way the main bulk of the monument (not open to hunting west of the East Branch of the Penobscot River, as made clear by this map) is accessed practically divides it into two areas. To the south the Katahdin Loop Road (accessed via Hwy 11 and Swift Brook Road from Stacyville) offers a 17-mile scenic drive with a few overlooks and trailheads for hikes of various lengths. To the north, the Matagamon Entrance (accessed via Route 159, the Grand Lake Road) gives access to more hikes and to the East Branch of the Penobscot River for paddling.

Monument roads are usually open to vehicles from Memorial day to the first week-end of November. Although a bit rainy, autumn is the most beautiful time to visit, Although on the chilly side, temperatures are pleasant, and bugs rare. In that part of Maine, the peak color usually occurs on the last week of September of the first week of October, since Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument is located in zones 4 and 7 of the following maps: historical peak foliage, current foliage conditions.

Short hikes and Katahdin Loop Road

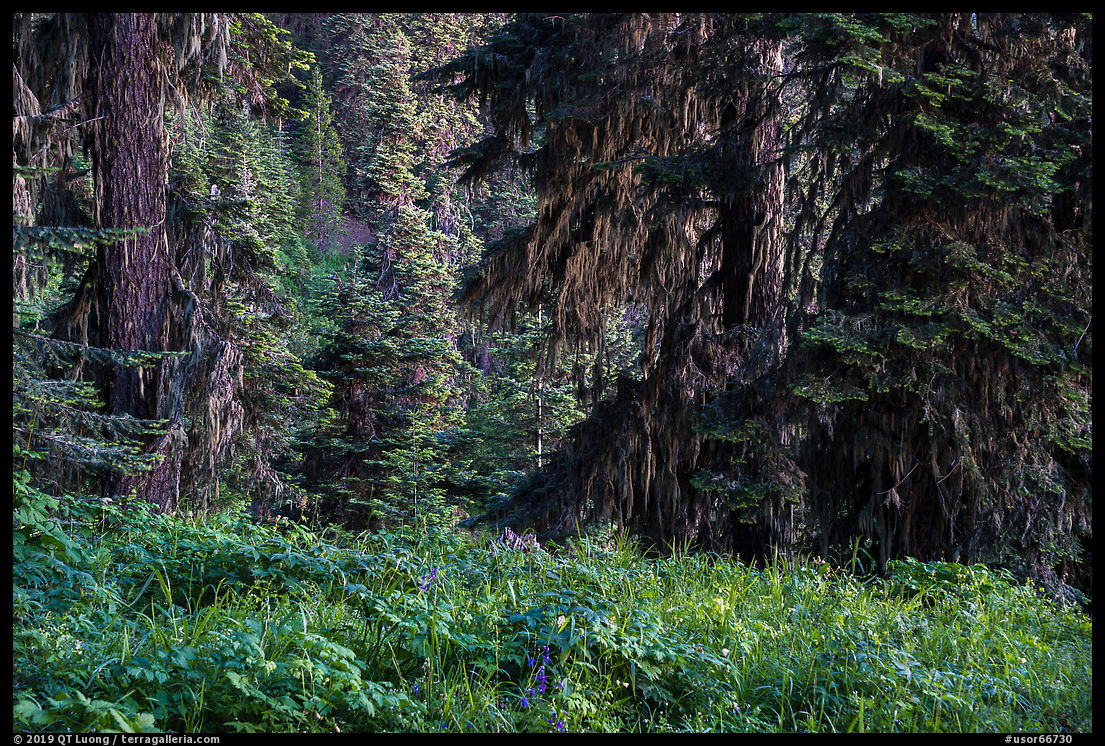

On the first day, after a late start, I started exploring the Katahdin Loop Road (map). In the rainy conditions, views of mountains were obscured by clouds, so I went for hikes in the forest close to the monument’s entrance. That area has marshes, one of which is visible from the road right at the start of the loop, eskers – ridges of sediments deposited by meltwater from a retreating glacier, and a mature forest, so there is quite a bit of biodiversity along the short Esker Trail and Deasey Pond Trail. However, the forest there is mature, so autumn foliage comes in pockets rather than vast swathes.

Like most of the roads in the Maine North Woods, the Loop Road wanders in a dense forest and seldom offers open views. However, the fall foliage is as beautiful as in any of the national parks, and unlike in them, the absence of traffic meant that I could drive at a slow speed and instead of keeping an eye on the road, look for small compositions of trees, kind of like what I did in a remote corner of Cascade Siskiyou National Monument, and stop whenever something caught my eye. It is surprising how many miles of trees you can walk or drive past before finding a satisfying arrangement of shapes and colors. A mile after the start of the loop, I came across the first view of Katahdin at a small pullout.

The most expansive roadside view in the monument is located at the Loop Road Overlook (Mile 6.4) from where you can see Millinocket Lake and Katahdin. The second day featured cloudy weather with rain showers. After filmmaker Brendan Hall had joined me for a day and half, we had come shortly after sunrise to the Loop Road Overlook, hoping for some luck, but the light did not show up. However, the sky was dark and textured enough, and the overcast conditions revealed the foliage colors. Late in the day, the sky had cleared quite a bit, so we returned to the Loop Road Overlook for a late afternoon photography session where I found the landscape transformed by the light compared to the morning.

Orin Falls

We drove the spur Orin Falls Rd (Mile 15.5) to a trailhead. Like many others in Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, the trail to Orin Falls was an old road, forming the International Appalachian Trail (IAT), an extension into Canada of the famed Appalachian Trail that ends at Katahdin. It feels different from the recently built trails such as Esker Trail and Deasey Pond Trail that are narrow and snake in the forest. It would be more fun to ride a mountain bike (allowed on most monument trails) than to walk on that section of the IAT, however, the pace of riding may have been too fast to appreciate the beautiful autumn foliage along the way. The early forest along the trail was luminous and featured more aspen and birch trees than the trails I hiked the first day, and also more colorful foliage.

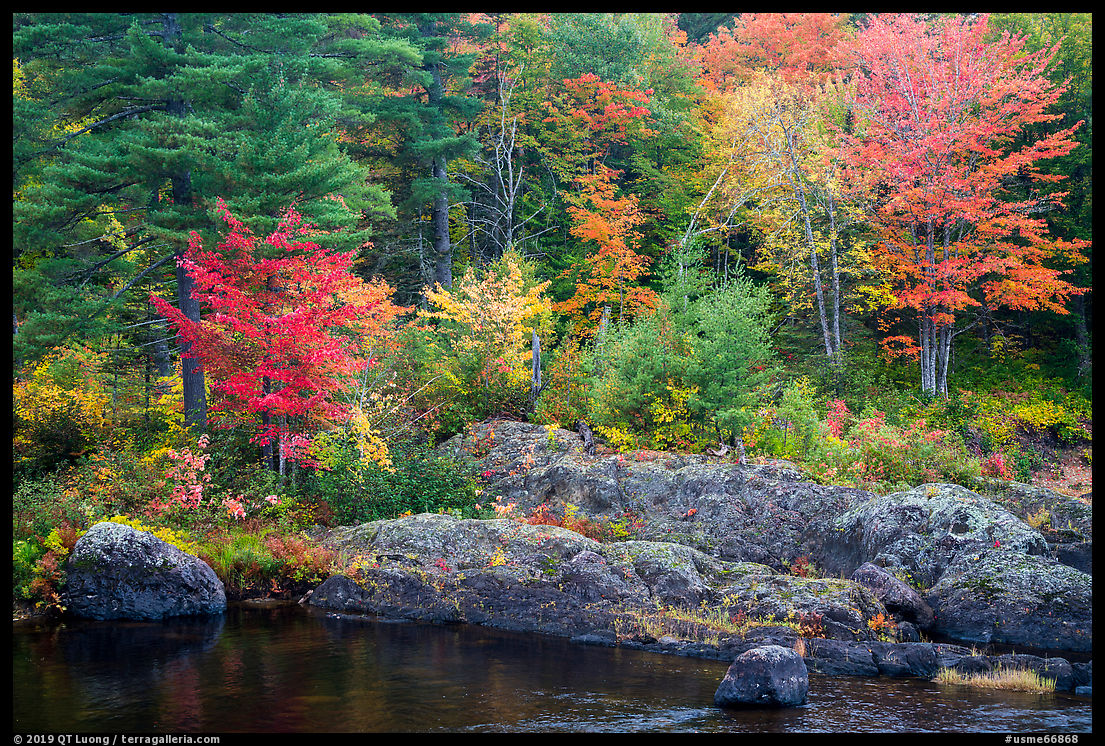

The trail narrowed, and led in 3.3 miles (one-way) to Orin Falls. Despite the name, don’t expect to see a waterfall there. On Maine rivers, a falls, counter-intuitively, designates whitewater that is navigable. What makes the setting there remarkable is that the Wassataquoik Stream flows between massive boulders, with the riverbanks adorned with fall foliage. Since it is quite open, I waited for a long time for a bit of clear sky, but since that did not materialize, I contented myself with intimate landscapes excluding the sky.

Lunksoos Camp

The Lunksoos Campground turned out to be the nicest of the three road-accessible campgrounds in Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, with a patch of grass by the river to pitch your tent, a boat launch, picnic tables, and a toilet, which is about as developed as the monument gets. It is the only place in the monument where water is available, at the nearby park headquarters, which consists of a few humble cabins where a pair of rangers live. The previous night, I had stayed at the Sandbank Stream Campground, but I thought that the setting of the Lunksoos Campground was more scenic, so with a clear night in the forecast, I returned there. Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument has some of the darkest skies east of the Mississippi River, and in the windless night, stars reflected clearly on the East Branch of the Penobscot River. The morning was also still, and fall foliage made for beautiful reflections.

Barnard Mountain

On the third day, taking advantage of a sunny morning, we made a beeline for Barnard Mountain. The 1621-feet mountain is reached via a 4.5 mile RT hike (900 feet elevation gain). From the trailhead (Mile 11.8), it first follows an old road along the IAT, and then switches back steeply for the last 0.8 miles on a narrow footpath. Like other peaks in the monument, Barnard Mountain is dwarfed by Katahdin, but it still rewards with a view, open only towards the west, said by Cathy Johnson from the Natural Resources Council of Maine to be one of the best in Maine, and the “not to be missed” spot in Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument. Given that opinion, it struck me that the footpath was built only in 2014, five years ago. We are still in the early days of a bright recreational future.

On the way, I had noticed Katahdin Brook, the outflow of Katahdin Lake which is visible from Barnard Mountain, but the sunlight was creating contrasty conditions in the forest. After driving around on the loop road, in the late afternoon, I returned to photograph Katahdin Brook in more even light.

Haskell Rock Pitch

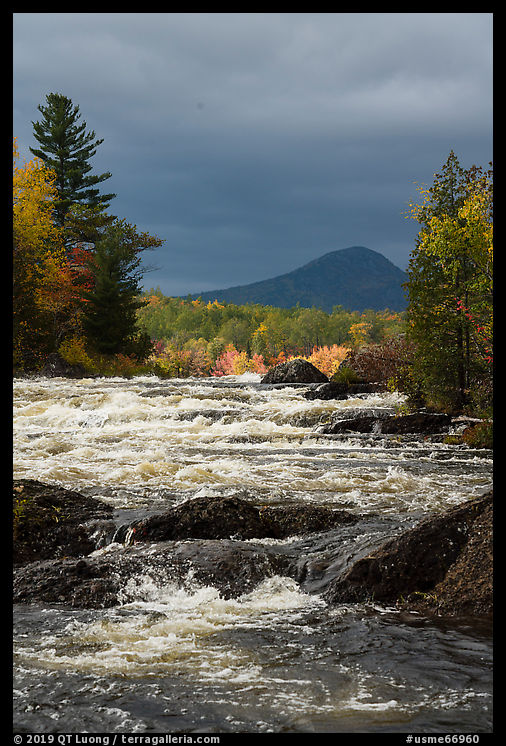

Rain returned on the fourth day. In the morning, I made the 1h30 drive from the south entrance to the north entrance, stopping in Patten for breakfast – my only non-camping food of the trip. Just before the monument’s north entrance, and before a river bridge, a lodge offers amenities. Once on Grand Lake road, if you miss the left turn off for the monument, shortly thereafter the highway turns into an unpaved road. After turning and driving 4 miles on another unpaved road, I parked at the road’s end and hiked another old road section of the IAT (4 miles RT) to Haskell Rock Pitch. The magnificent rapids over the East Branch of the Penobscot River are the most impressive in the monument. In Maine parlance, a pitch is a whitewater that’s too rough to navigate in a canoe, so higher than a “falls”. Although I paddle only occasionally, I could see how much variety the river would offer. Sam Deeran, the Deputy Director of Friends of Katahdin Woods and Waters, to whom I am most grateful for his help in planning my trip, considers the three rivers: East Branch of the Penobscot River, Seboeis River, and Wassataquoik Stream, to be the heart of Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument.

I lingered at the Haskell Rock Pitch, taking in the sound of water, looking for ways to frame Bald Mountain and for angles over the Haskell Rock (a 400 million year old puddingstone rock), but mostly waiting for the weather to change, since I had learned in the previous days that it can go from cloudy to clear and vice-versa in the blink of an eye there. It did change, and I was gifted with images that I didn’t expect at all while I was hiking under intermittent showers and a grey sky. After making it back to my car right at nightfall, I drove to Acadia National Park, where my experience couldn’t have been more different.

It’s not that I saw moose on two occasions in Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, whereas there is no permanent breeding moose population on Mount Desert Island. It didn’t bother me that the Blackwoods Campground in Acadia charged $30 per night, whereas the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument campgrounds were free. What disappointed me was that as I attempted to drive to Cadillac Mountain an hour before sunset on a weekend, the road to the mountain was outright closed by rangers for “congestion”. On the other hand, although on weekdays, except for the last day, I always saw at least another hiking party on each of the trails I undertook, I could count on the fingers of my hands the total number of other cars I saw during the four days in Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument. Even compared to nearby Baxter State Park, which has been kept a low profile and undeveloped, exploring Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument is, for now, a backcountry affair. I liked it that way. You can still beat the future crowds in Maine’s rough gem.

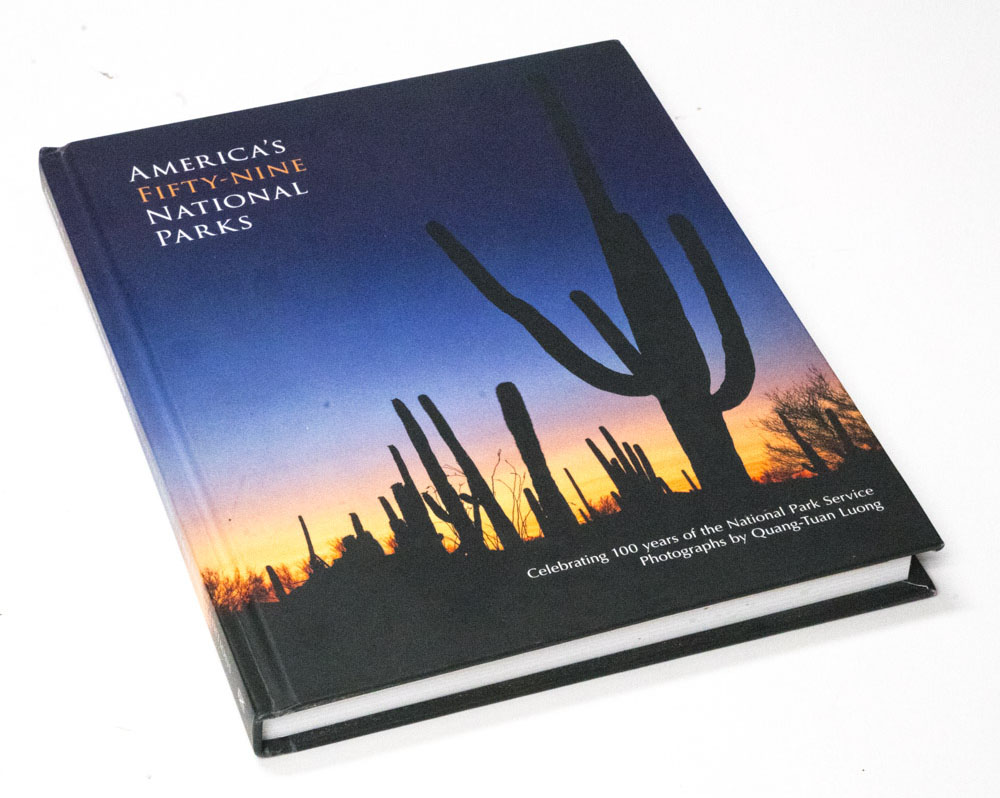

More pictures of Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument