The Third Wave

In April this year 2019, the next day was also forecast to be rainy, but having learned that there is much more than the Wave in the Coyote Buttes North permit area, I entered the lottery. Currently, 20 hikers are allowed into Coyote Buttes North each day. Half of the permits are awarded months in advance through an online lottery, and the other half are drawn for the next day via a daily 8:30am walk-in lottery taking place at the BLM visitor center in Kanab, Utah (details).

On that day, the odds of winning the lottery turned out to be slim: 144 applicants for 10 permits. But my main goal in coming to the building was not to seek a Coyote Buttes North permit, but instead a Coyote Buttes South permit, which is subject to an identical quota. I was assigned #1 for that second lottery, which takes place around 10am after then Coyote Buttes North lottery, and with only 14 applicants, the odds of winning were much better!

Besides not including the Wave, another reason for the lesser popularity of Coyote Buttes South is the remoteness and longer drive not accessible to all vehicles. Besides the rocky spots, there are spots of deep sand and the tracks are often deep with a high ridge in the middle, sometimes combined with inclines. Although there are quite a few roads where 4WD is recommended but actually not necessary, this is not the case here, and from what I’ve seen an AWD vehicle will not make it. Together with your permit, the BLM provides you with a map indicating mileage and road numbers, which I have found adequate to navigate the confusing maze of primitive ranching roads in the area provided you keep track of distances, since the road numbers are surprisingly well marked on metal posts.

Coyote Buttes South is a large, 1700-acre permit area. The two trailheads and main formations are about 3 miles apart on foot, and as the shortest road between them (5.5 miles) is not recommended because of deep sand, it took an hour and half to drive the 18-mile BLM-recommended route. Of the two trailheads, Paw Hole is the most accessible, and close to the teepee rock formations. It is only 2.5 miles from House Rock Valley Road, and without a 4WD vehicle, one could hike that distance. Evening light there would be best, but the day was overcast. That nevertheless brought out the incredible color saturation of the teepees.

The other official trailhead, Cottonwood Cove, requires more difficult driving, but there is a much larger variety of rock formations to explore. We encountered only one other party during our day. A user trail leads in a half mile to the first teepee rock formations next to a pond. From there, the trail vanishes and you need to scramble over rock and sand.

The light wasn’t great that day, to say the least, but I could nevertheless ascertain that Coyote Buttes South compares quite well to the Coyote Buttes North. Coyote Buttes South is one of the marvels of the Southwest, and a good example of an area which is under the radar not because of lack of merit, but rather because it is overshadowed by a better known area. With a bit of research, there is still much to find. I noticed quite a few whimsical rock towers, but since the day was overcast, I hoped I could have photographed them against a more attractive sky.

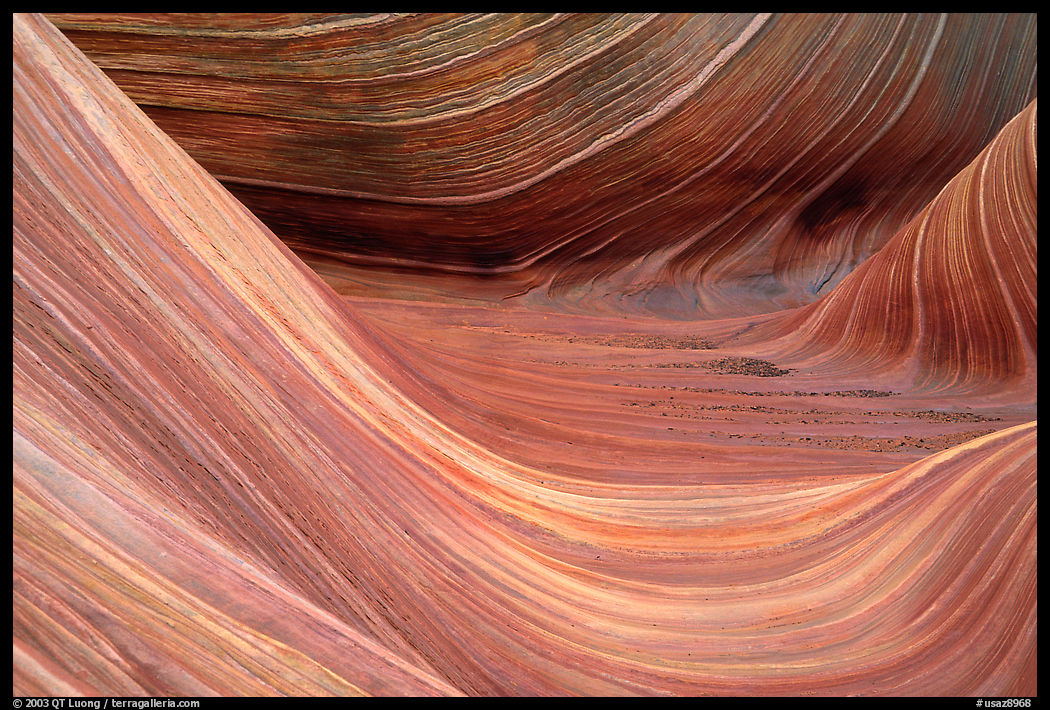

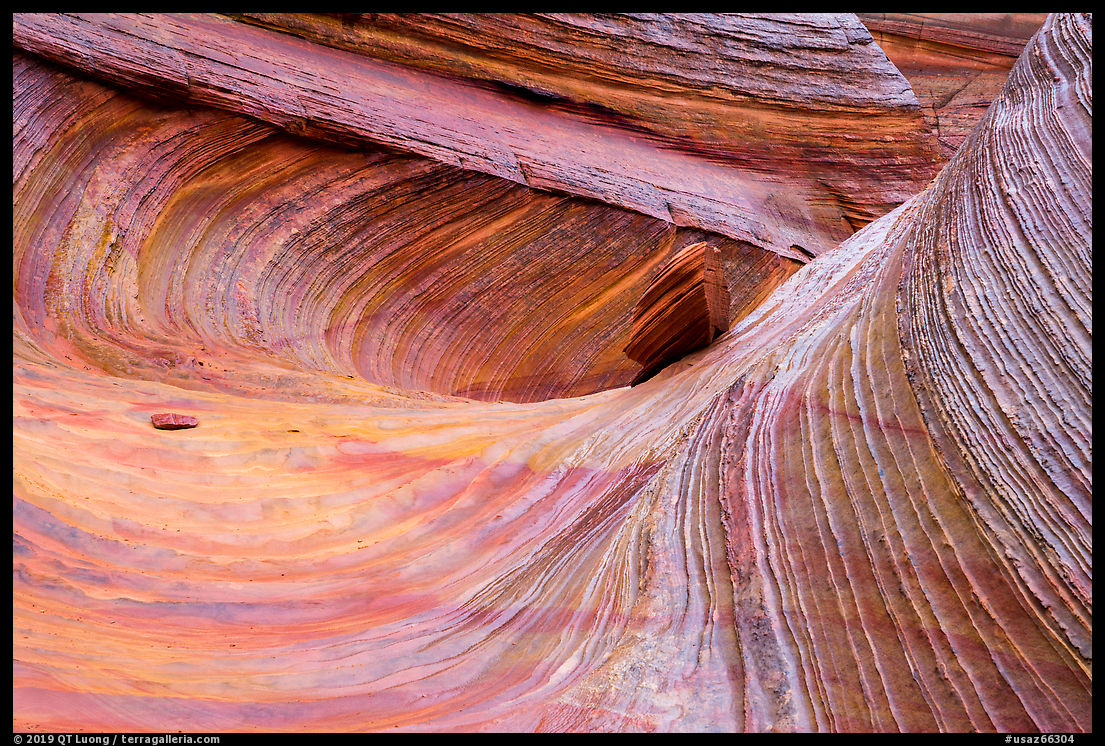

I hiked in the northwest direction for about a mile before turning back in steady rain. Half-way, a spot at the edge of a terrace offered a higher viewpoint over a lower terrace, mitigating the need to photograph against the cloudy sky. After scrambling down, we found the formation called the “Third Wave” – the “Second Wave” is located in the Coyote Butte North permit area, not far from the Wave.

The Third Wave is smaller than the Wave. When you first see it, the formation isn’t that impressive, but it would be have been a mistake to turn around without looker further. Like at the Wave, the striations are quite fragile, and it is important to leave them as you found it so that others may have a chance to enjoy them. This means avoiding trampling as much as possible. I walked across the formation only one time before going back.

That was enough to find an angle from which, thanks to the arrangement of swirls and striations, the Third Wave stood out. It has more rainbow colors than the Wave, and the rain intensified them, as can be seen by comparing the dry and wet portions of the rock. Like I did when I photographed the Wave, I excluded the blank sky from my compositions. The images below result from a very slight change in viewpoint, with four different focal lengths ranging from 17mm to 100mm. Which one do you prefer?

1

2

3

4