The Trouble with Wilderness

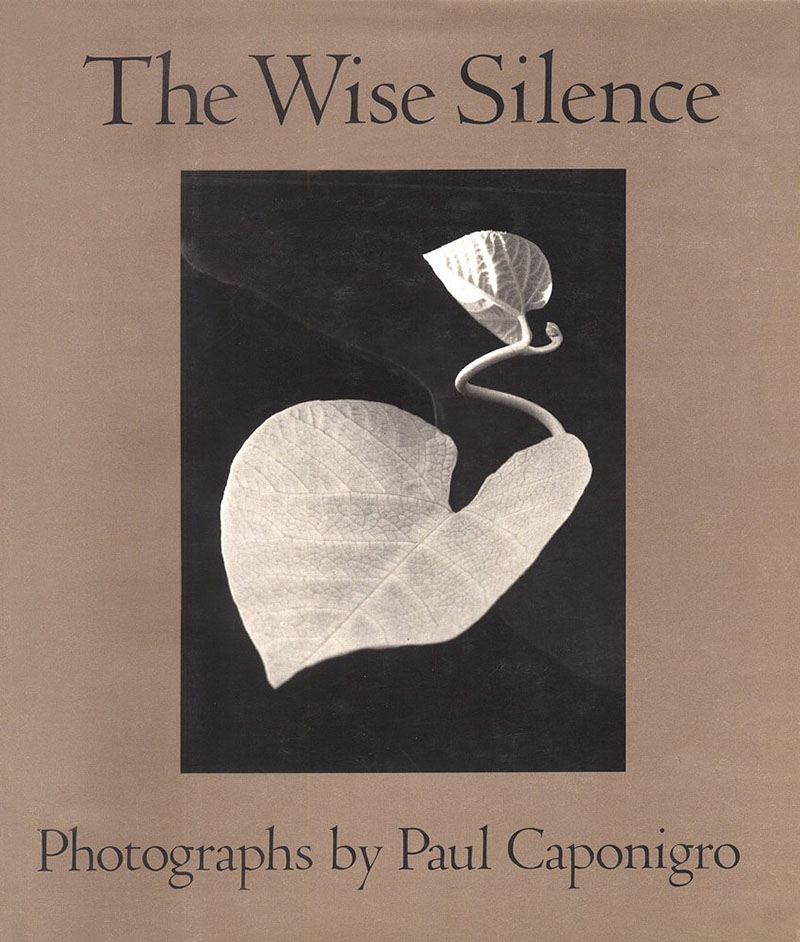

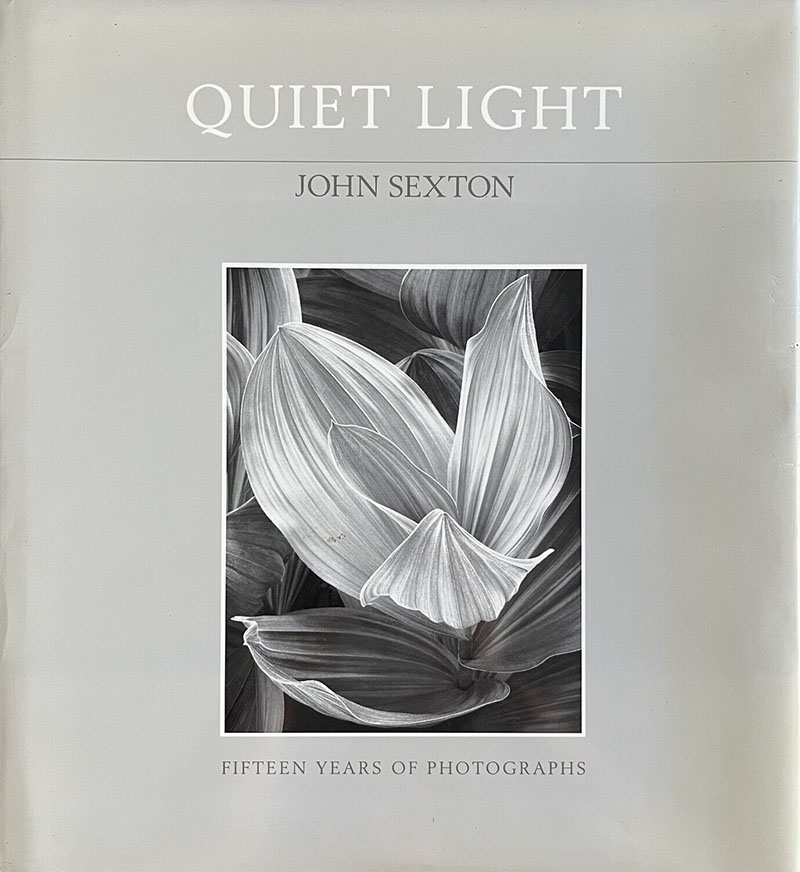

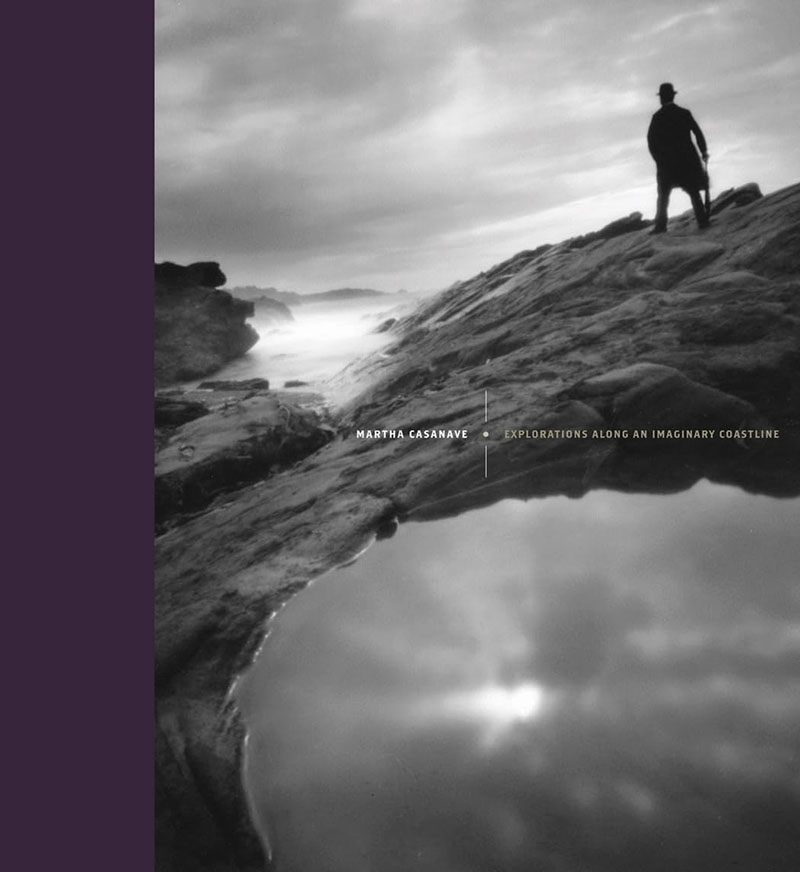

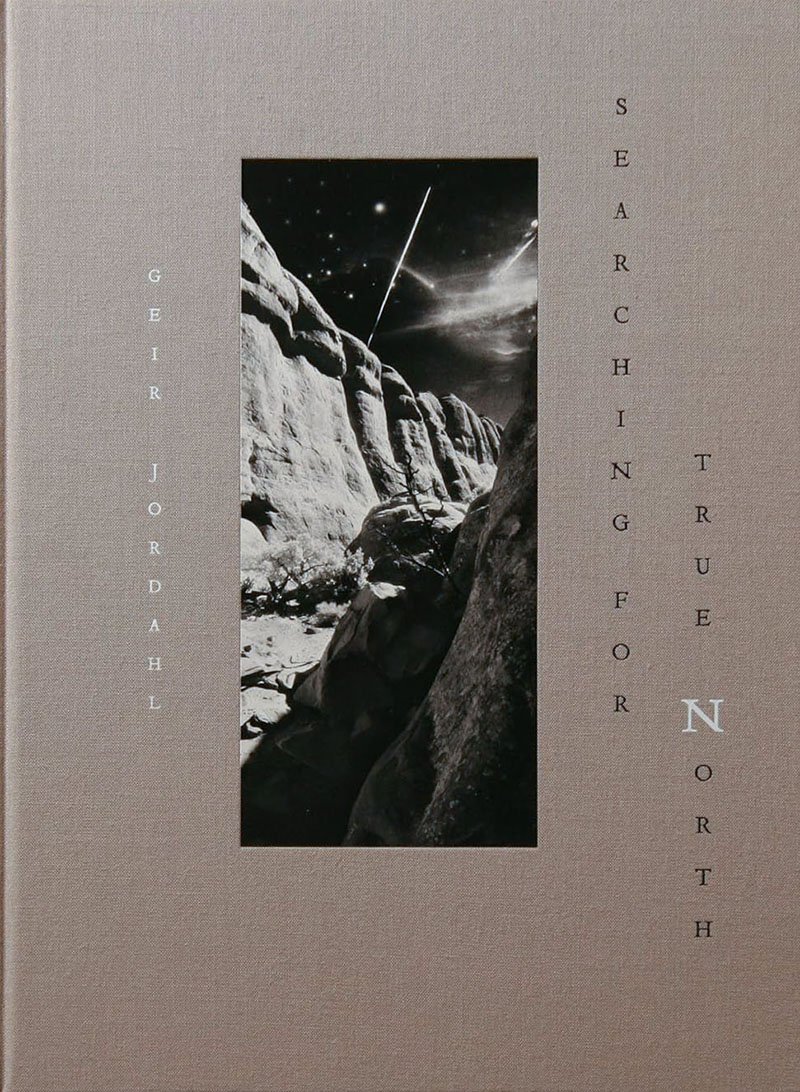

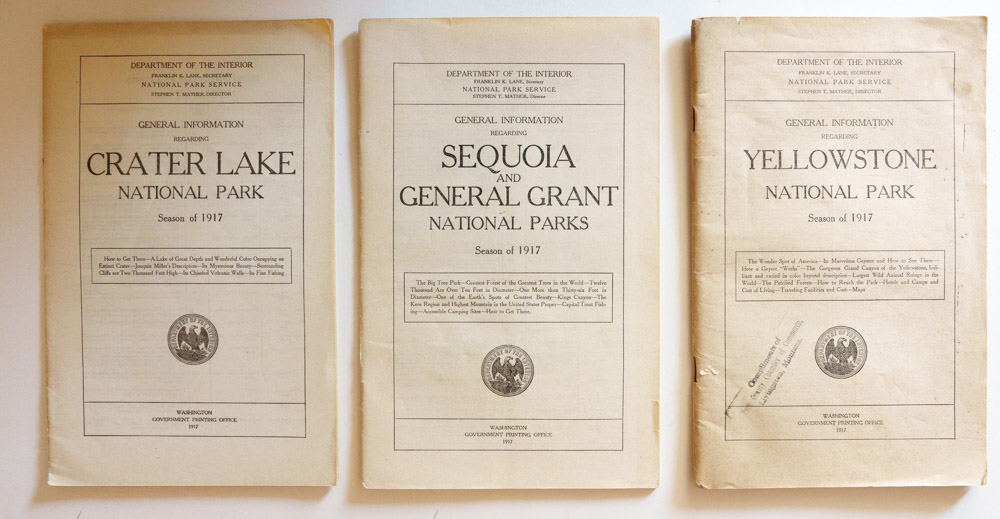

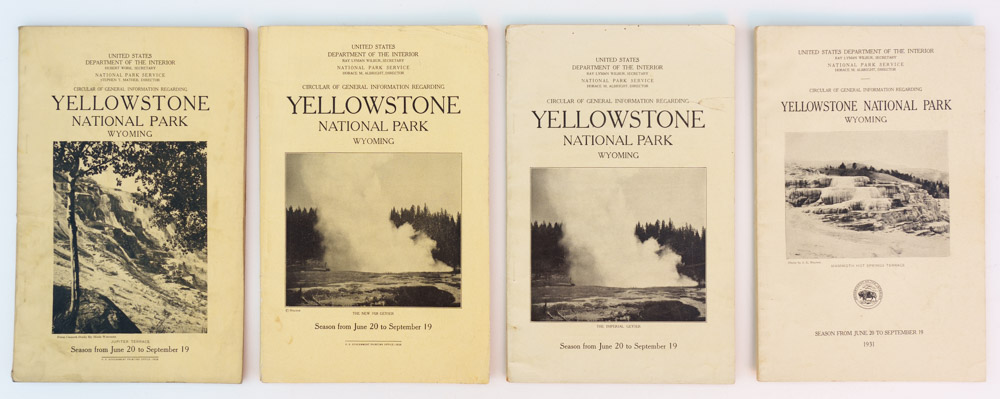

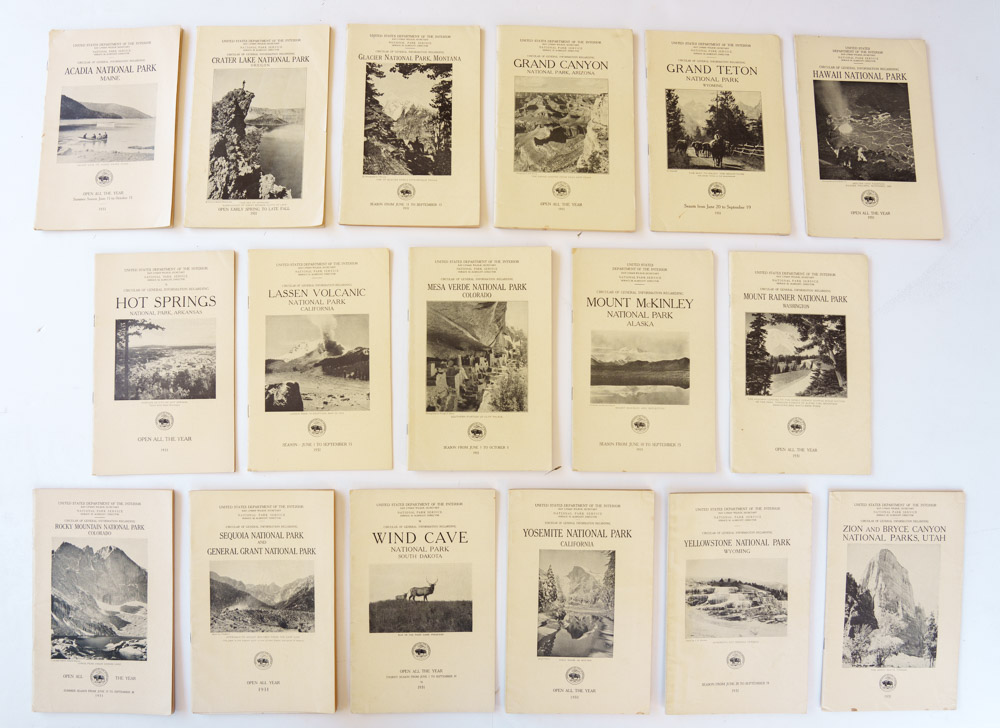

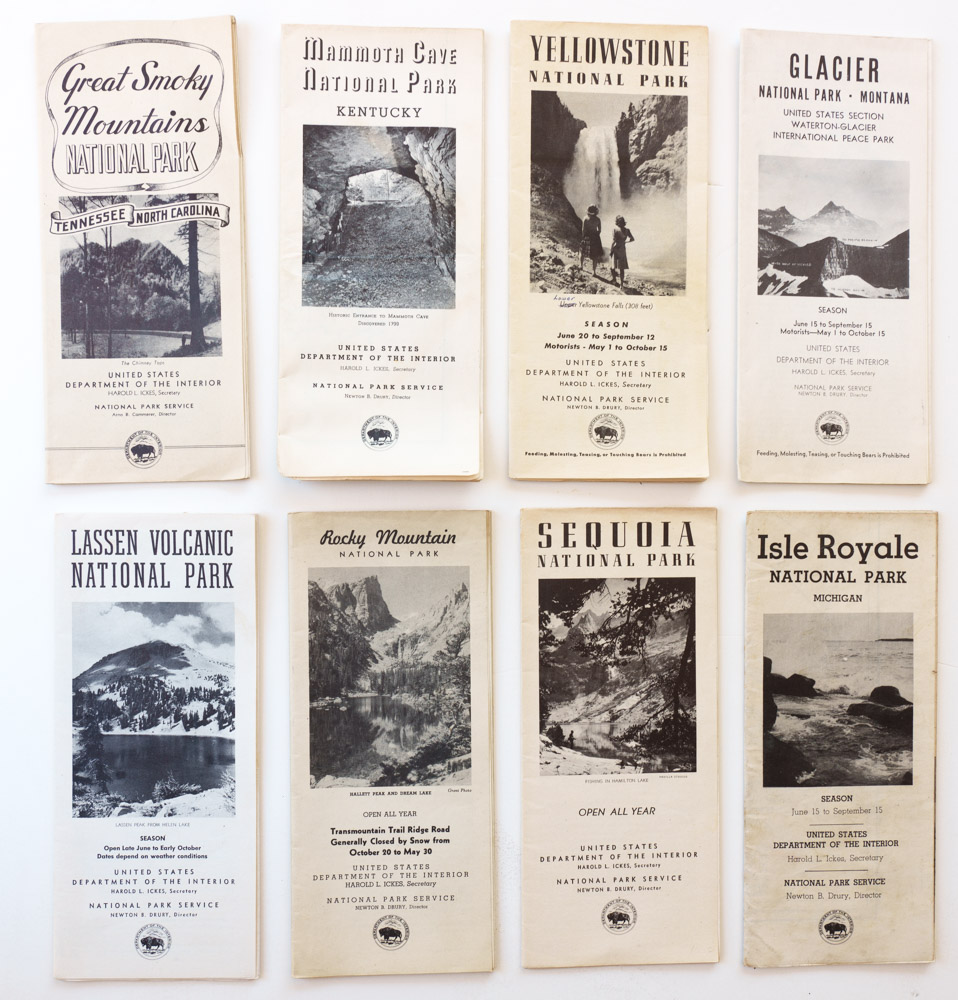

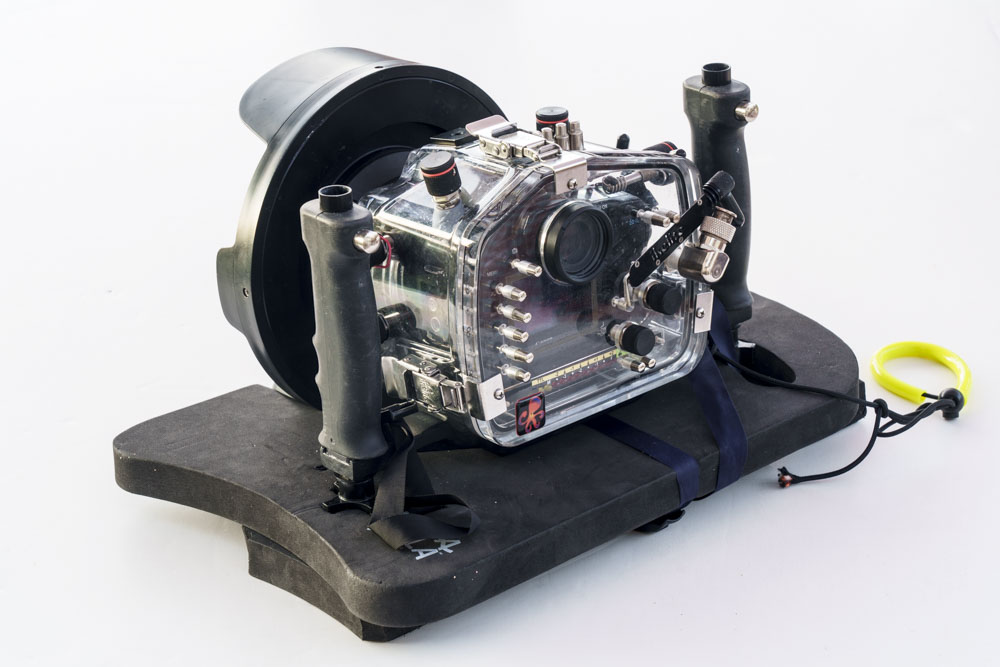

Finding meaning often begins with crafting a personal narrative. When we shape our experiences into stories, we discover clarity, purpose, and a deeper connection to ourselves. With that in mind, while reflecting on my work in landscape photography, I realized that its development mirrored the historic evolution of the genre, and also of environmentalism. I’ve crafted a more detailed story, however, what follows is a quick outline. I picked up a camera to document the High Alps in the documentary spirit of the 19th-century American survey photographers. In thirty years of nature photography in America’s public lands following the tradition of conservation-minded, expressive photographers of the modernist era such as Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter, I became the first to photograph each of the 63 U.S. National Parks in large format. The post-modern era brought to photography the detached artistic vision of the New Topographics and to environmental thought the shift from preserving the wild as sacred and separate sanctuaries to also acknowledging it in human-influenced environments. In that spirit, I extended my work to the infrastructure of our experiences of nature and the landscapes of the places where we live.

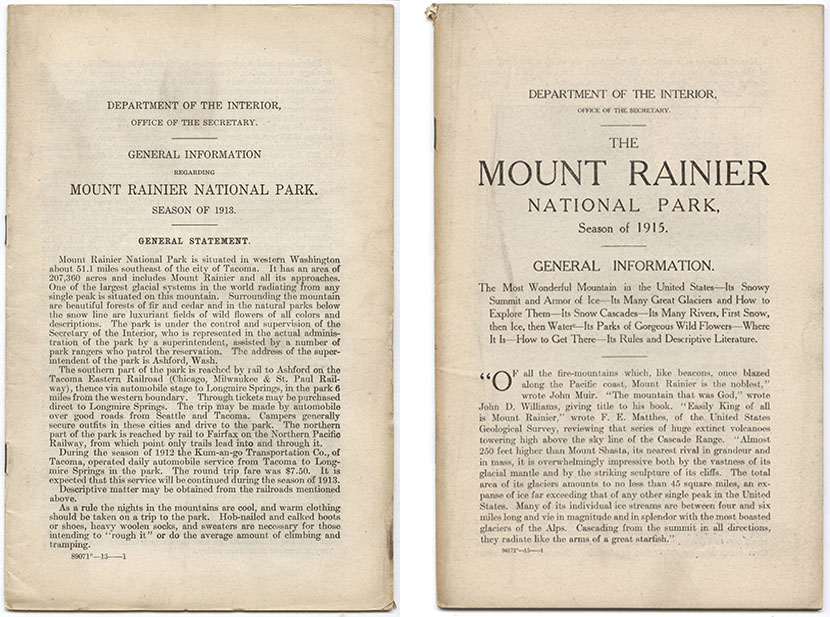

Ironically, my work in the national parks was the accidental catalyst for the later evolution. After Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan invited me to be part of their PBS film series The National Parks: America’s Best Idea (2009), I was privileged to meet some artists and writers interviewed in the series at promotional events. Among them, ranger Shelton Johnson, the series’s unexpected star, became a friend. Even though I did not meet all of the interviewees, I was exposed to their work for the first time, and several made a strong impression. Terry Tempest Williams spoke as beautifully as she writes. The eminent environmental historian William Cronon appeared repeatedly in the series to provide intellectual insights. I eventually found a collection of essays he edited, Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (1995), which examine the implication of different cultural ideas of nature for modern environmental problems. The essays challenge traditional ideas about nature, suggesting that what we perceive as “natural” is deeply influenced by human culture, history, and politics. Contributors argue that nature is not a pristine, separate entity but something humans constantly shape and redefine through their actions, beliefs, and technologies.

The idea was not entirely new. At that time, I was reading Alexander Wilson’s brilliant book The Culture of Nature: North American Landscape from Disney to the Exxon Valdez (1991). Wilson pioneered investigating how our experience of nature is shaped and commodified by cultural forces, how landscapes are manipulated for human consumption, and how media, tourism, and industry influence our perceptions of the natural world. Yet it is the essay The Trouble with Wilderness: or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature included at the beginning of Uncommon Ground that most deeply influenced my understanding of the concept of wildness and sparked my interest in photographing nature closer to home rather than only in distant parklands. My travels in the wilderness and countries around the world had been motivated by the desire to encounter otherness. Could I learn to see it next door? In the essay, Cronon critiques the romanticized concept of wilderness as an untouched, pristine space separate from human activity. He argues that this idealized notion of wilderness, rooted in 19th-century American thought, has led to problematic environmental attitudes. By elevating wilderness as the only “pure” form of nature, we overlook the environments in which most people live and diminish the value of everyday landscapes. Cronon encourages a rethinking of nature as something interwoven with human history and culture, advocating for a more inclusive and responsible relationship with all environments—not just remote, protected wilderness areas. The influential essay is reproduced on Cronon’s website, but since it exceeds 10,000 words, I am providing a “Cliff notes” version below the photographs.

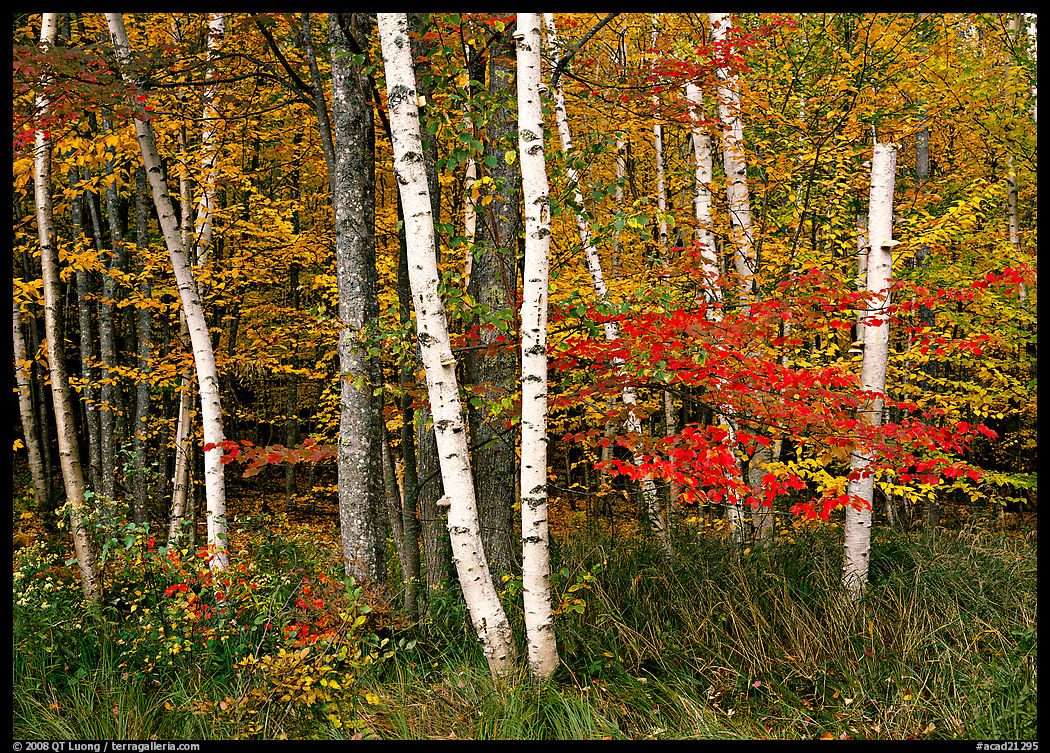

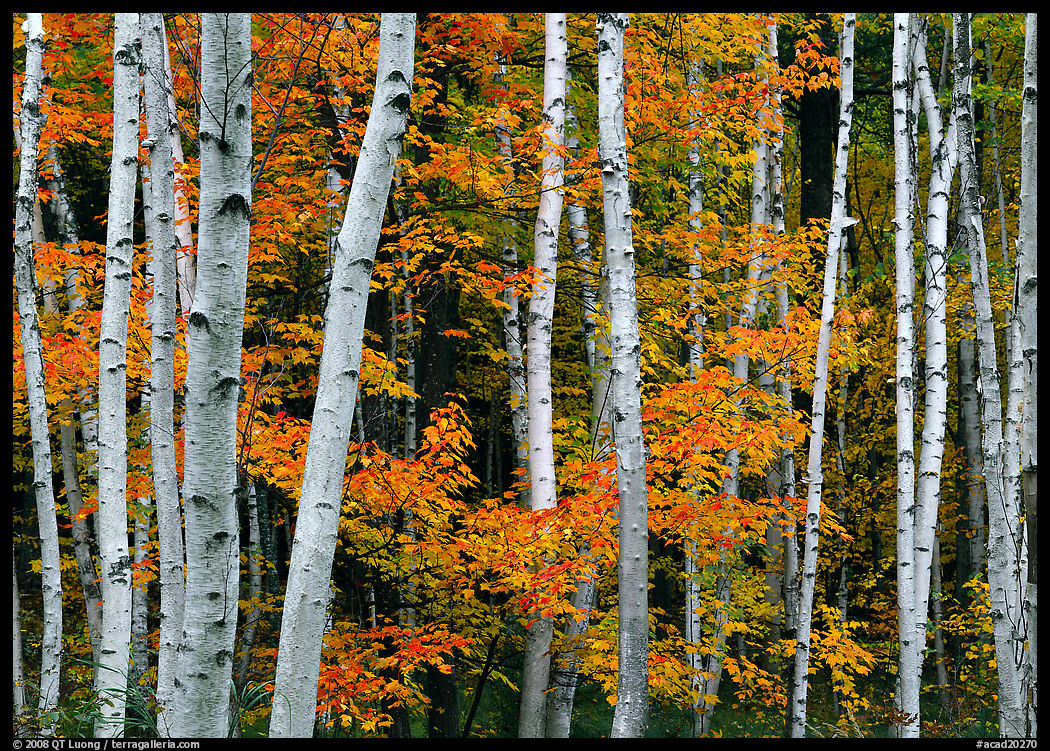

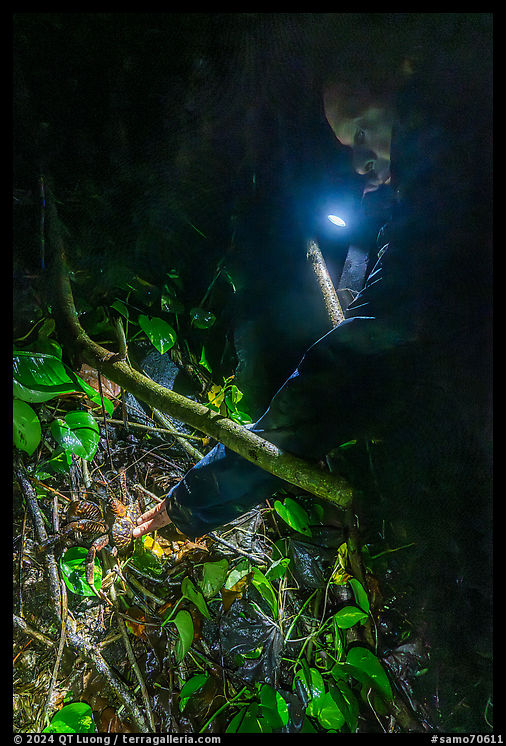

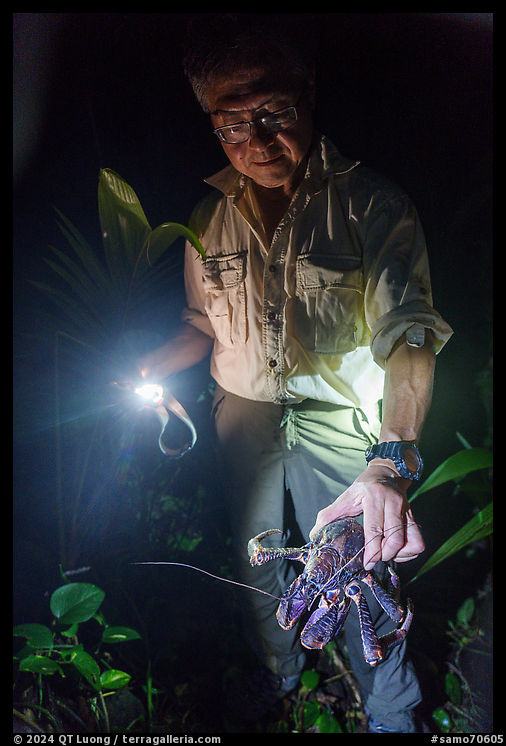

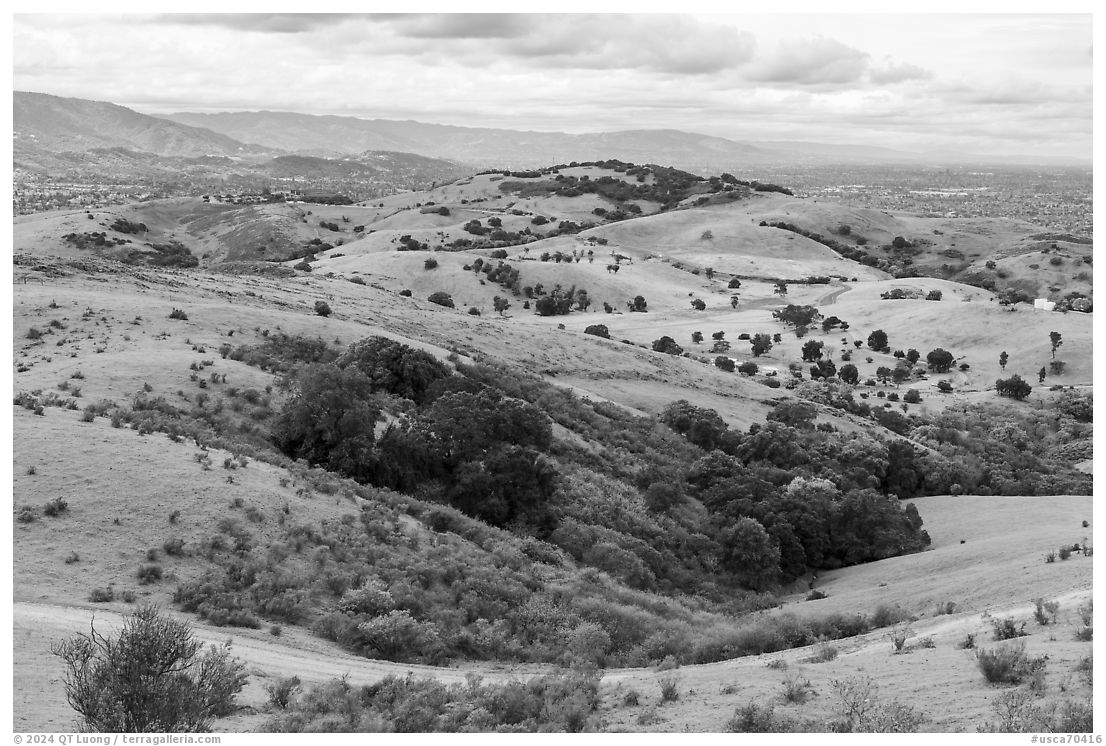

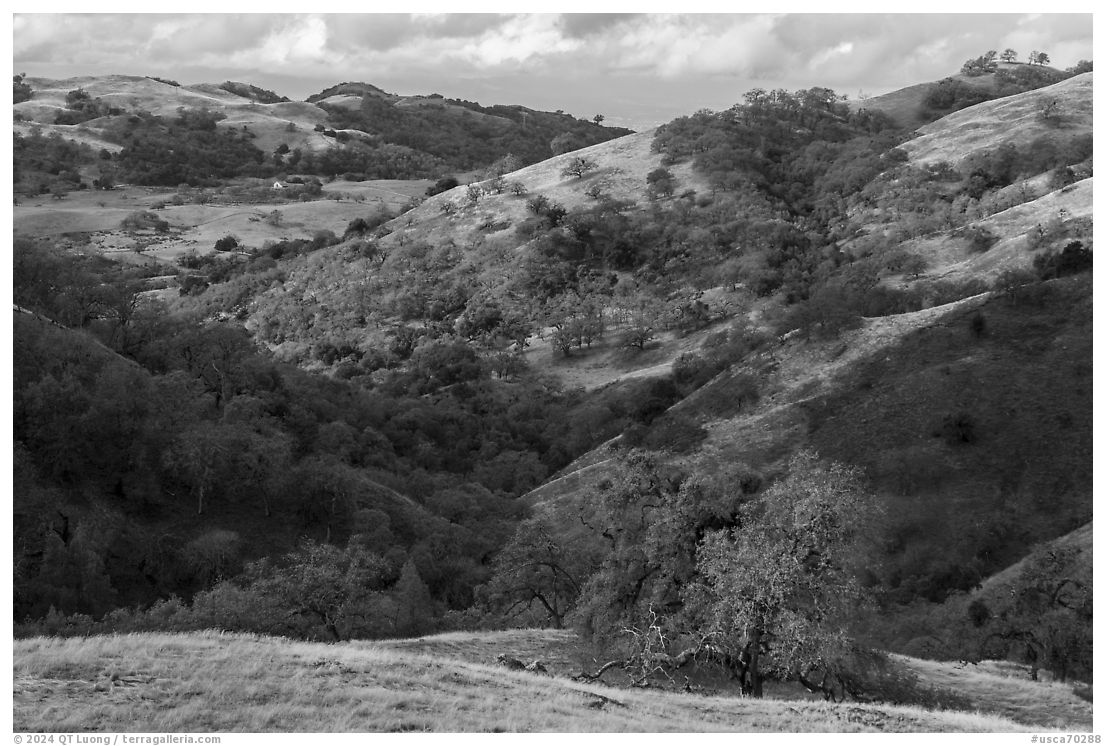

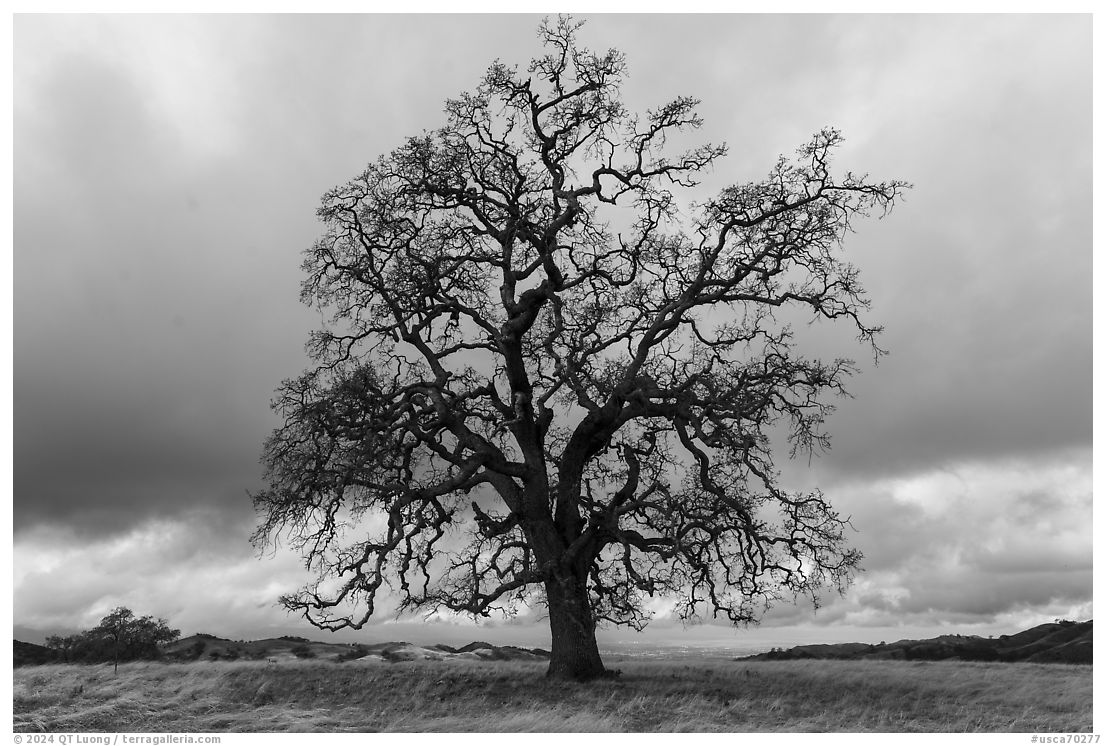

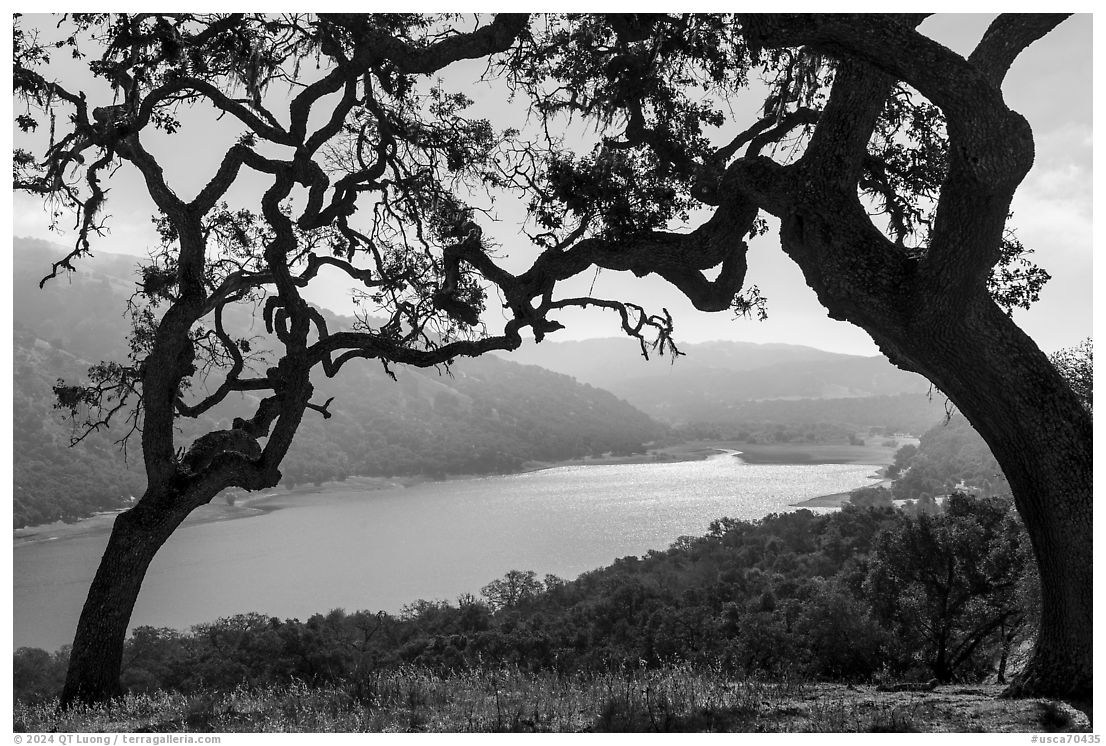

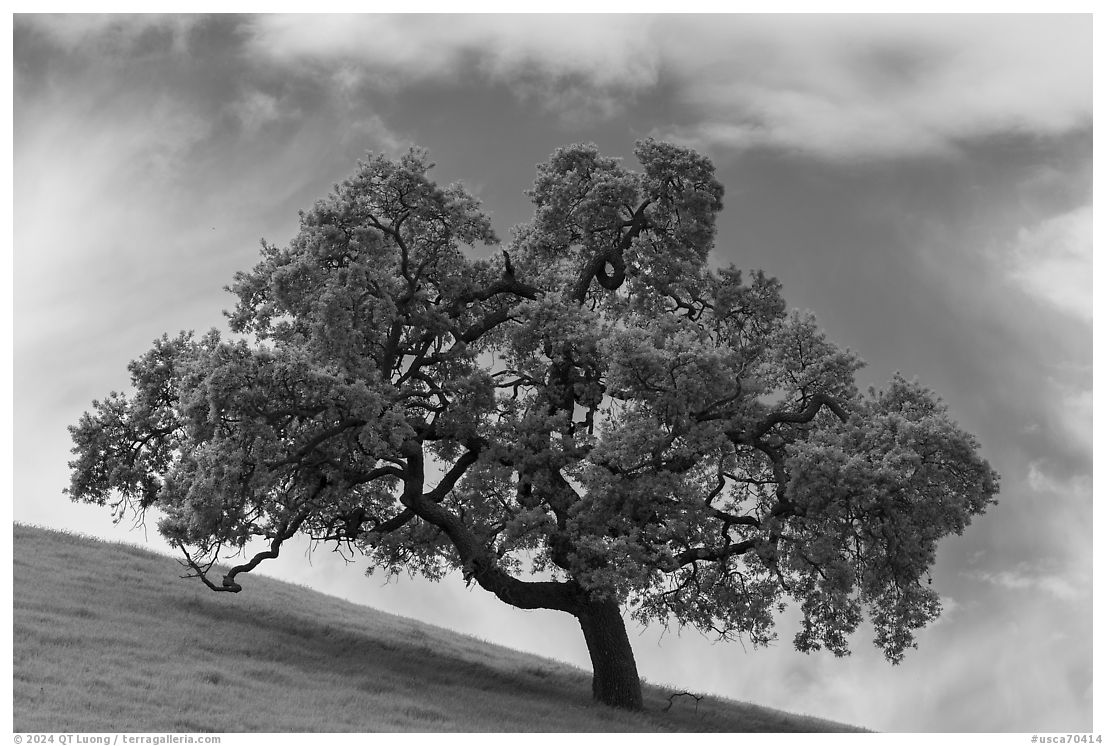

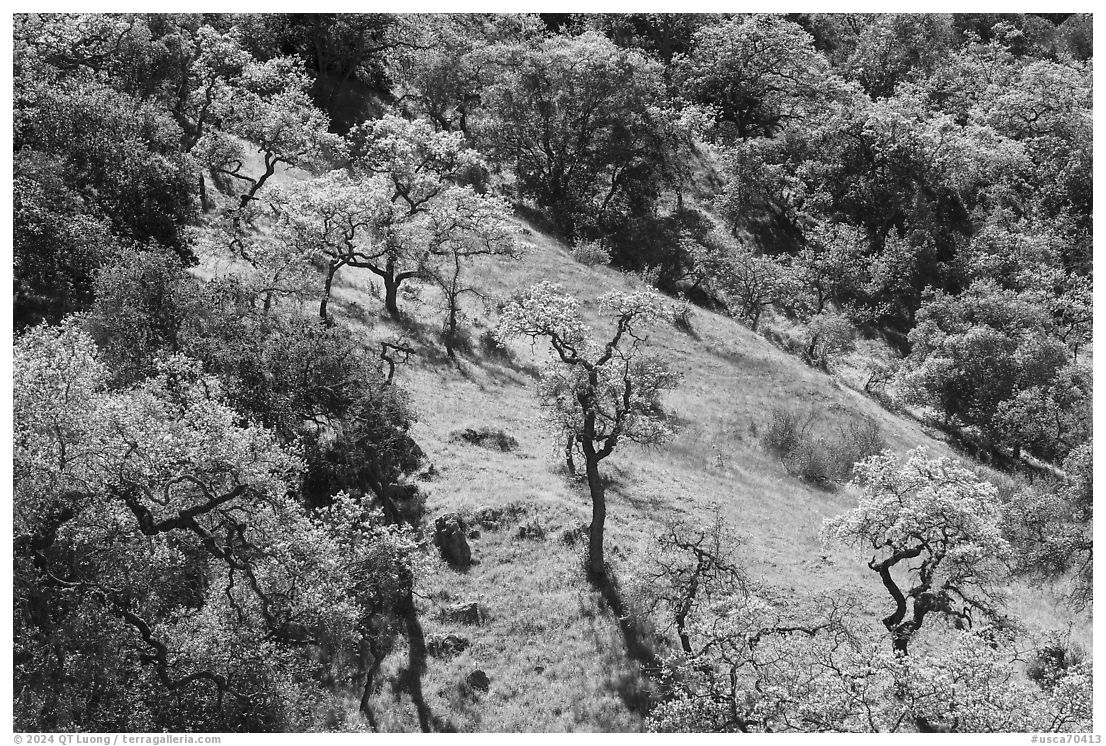

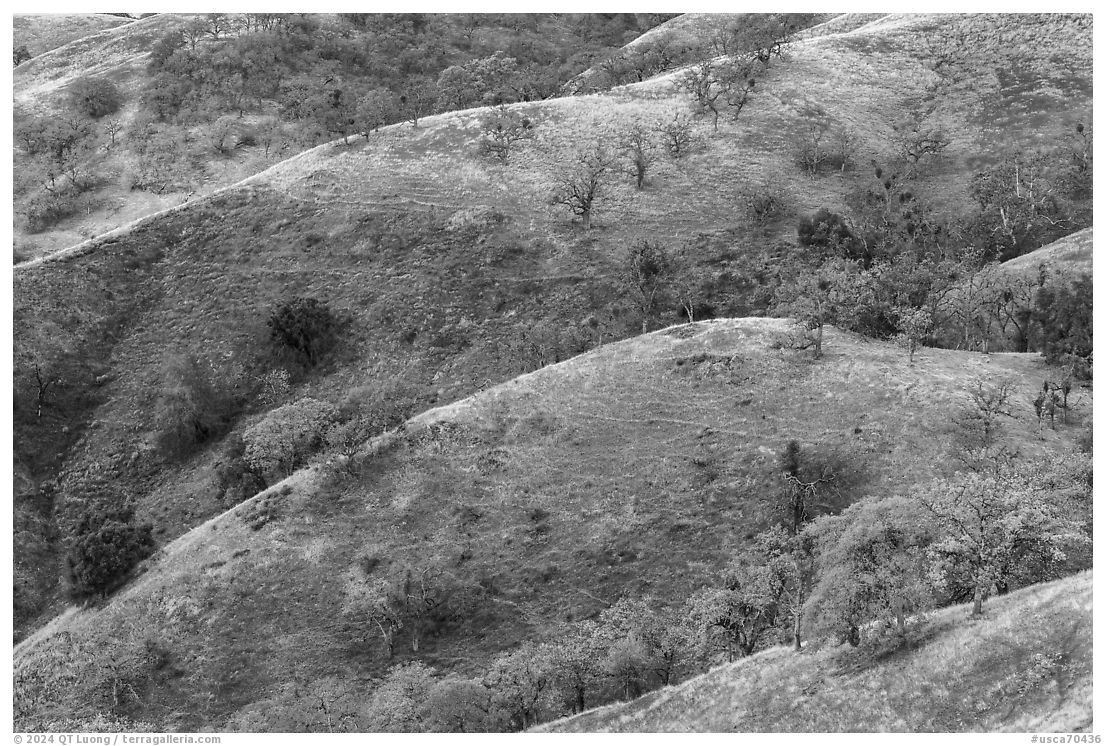

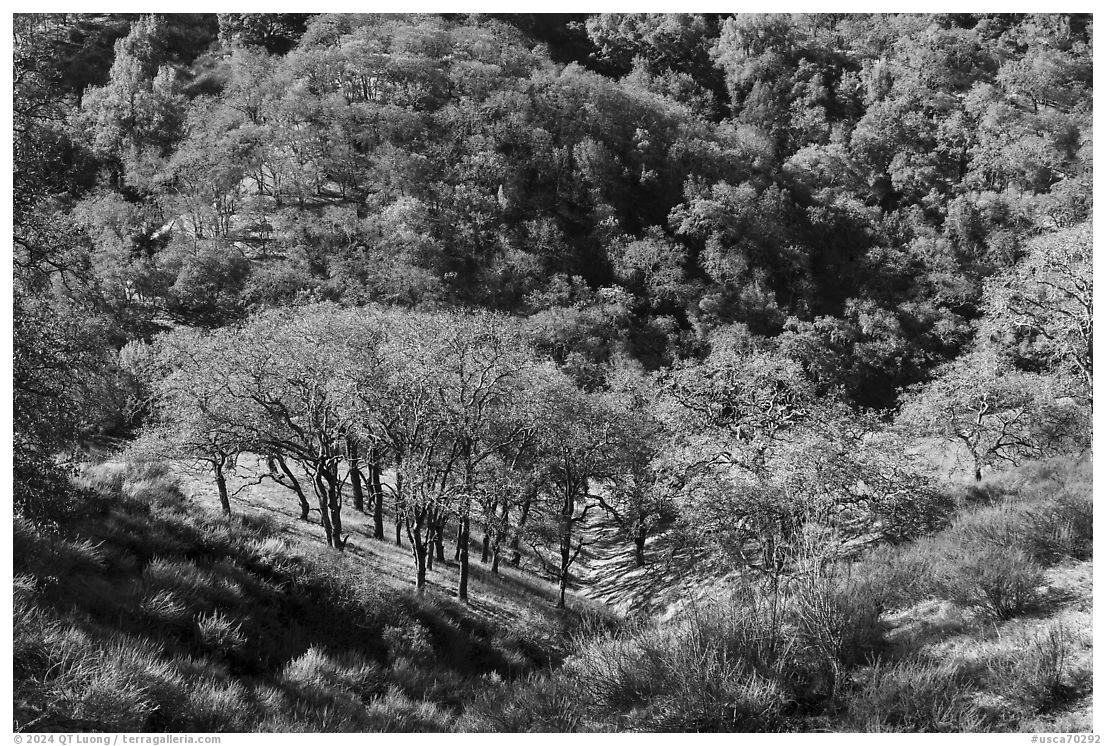

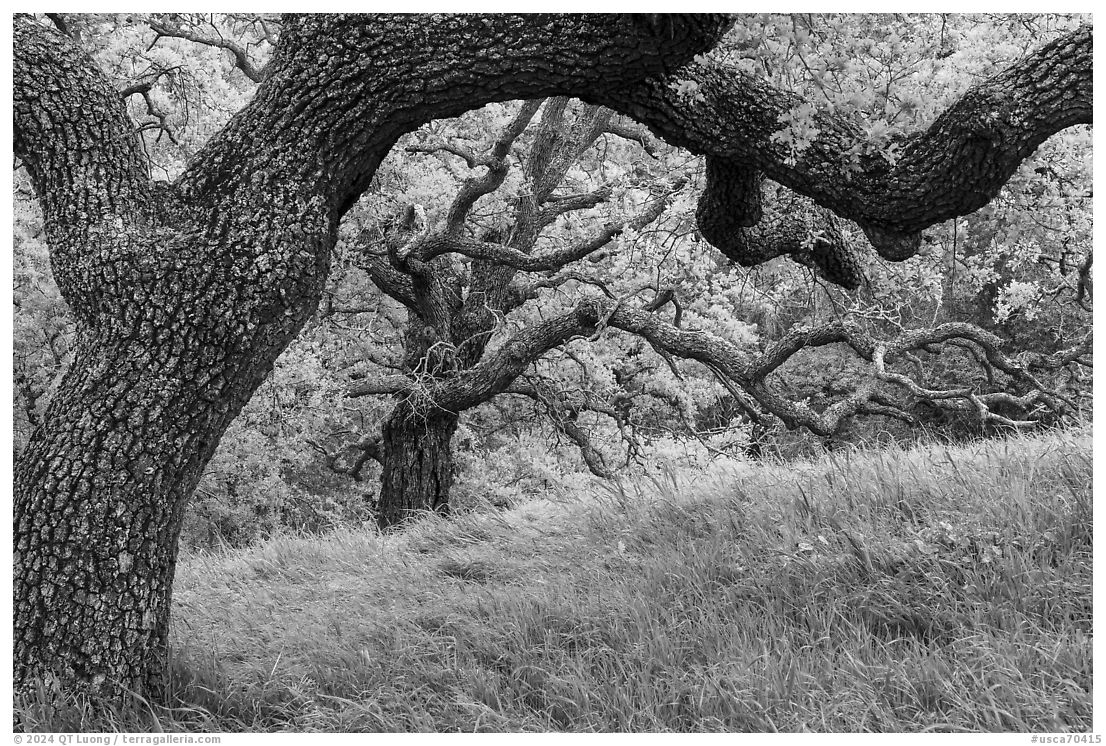

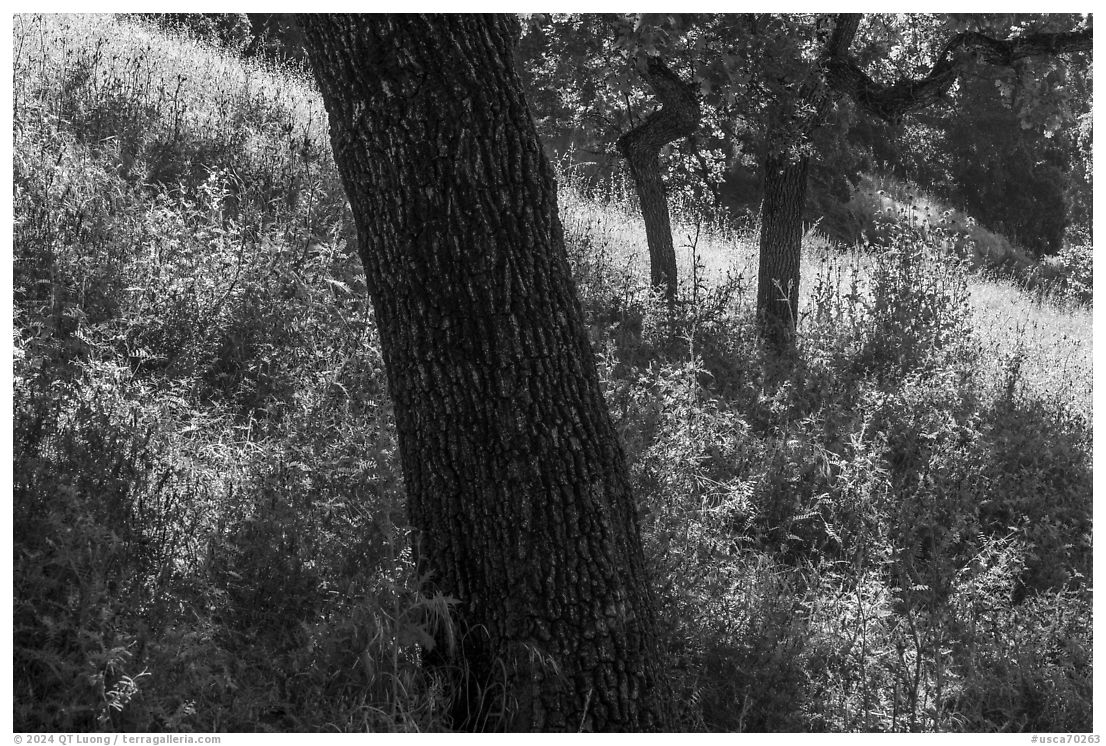

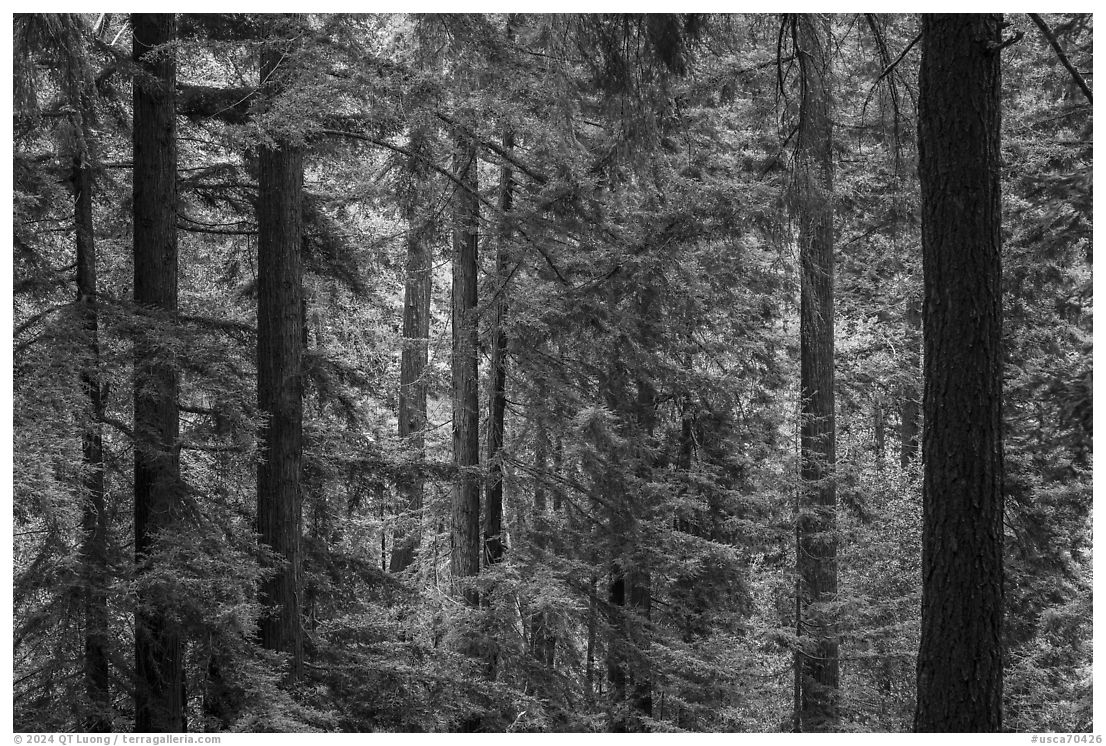

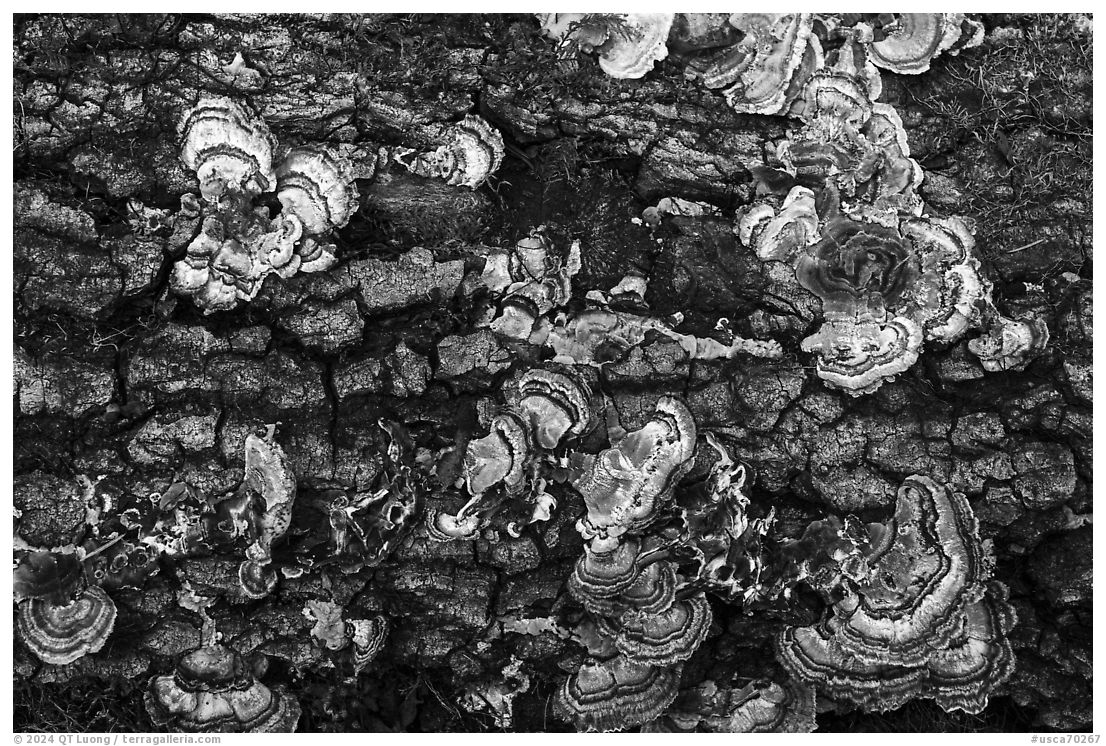

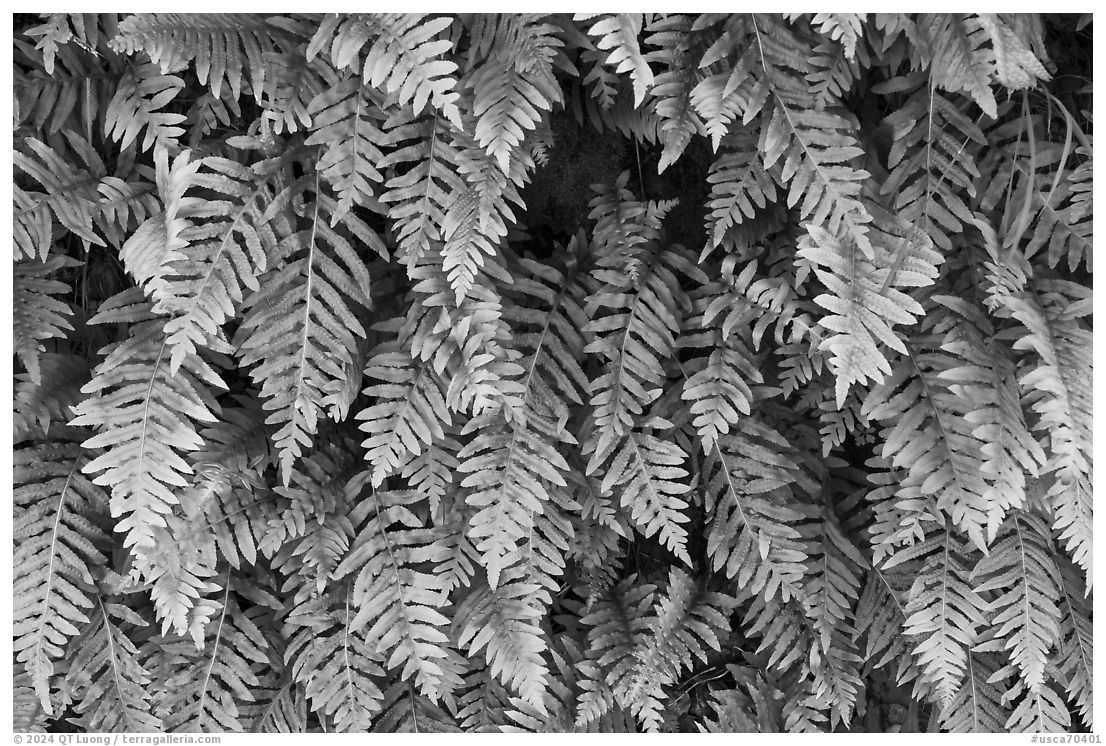

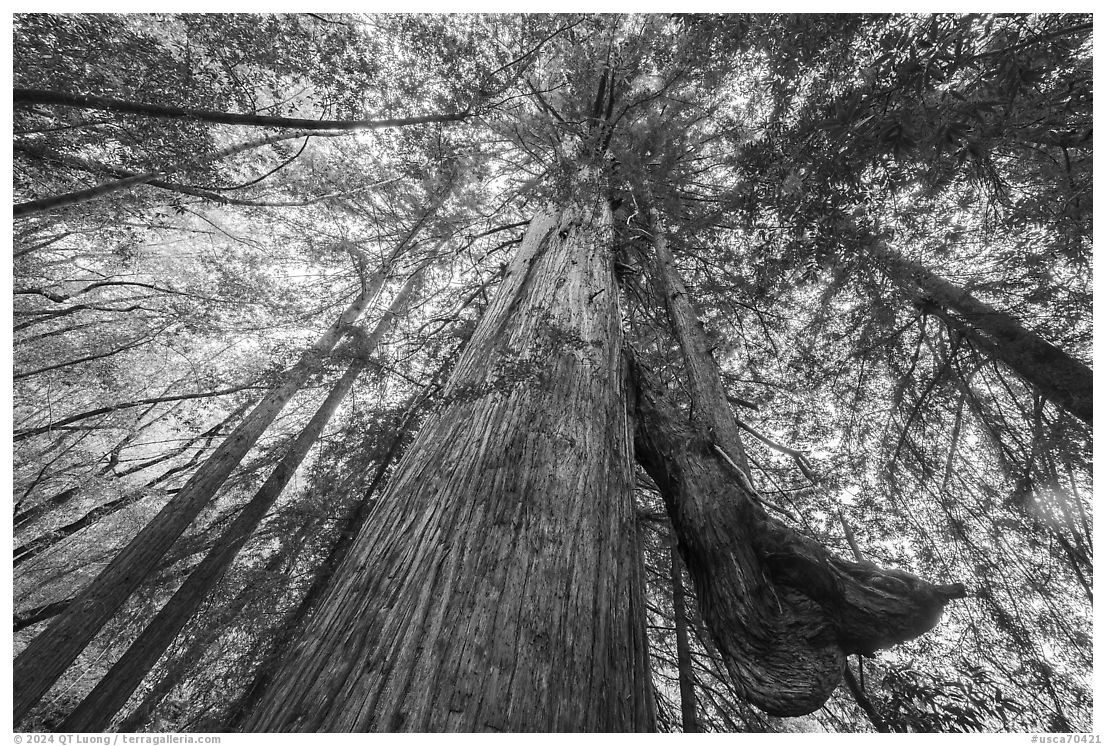

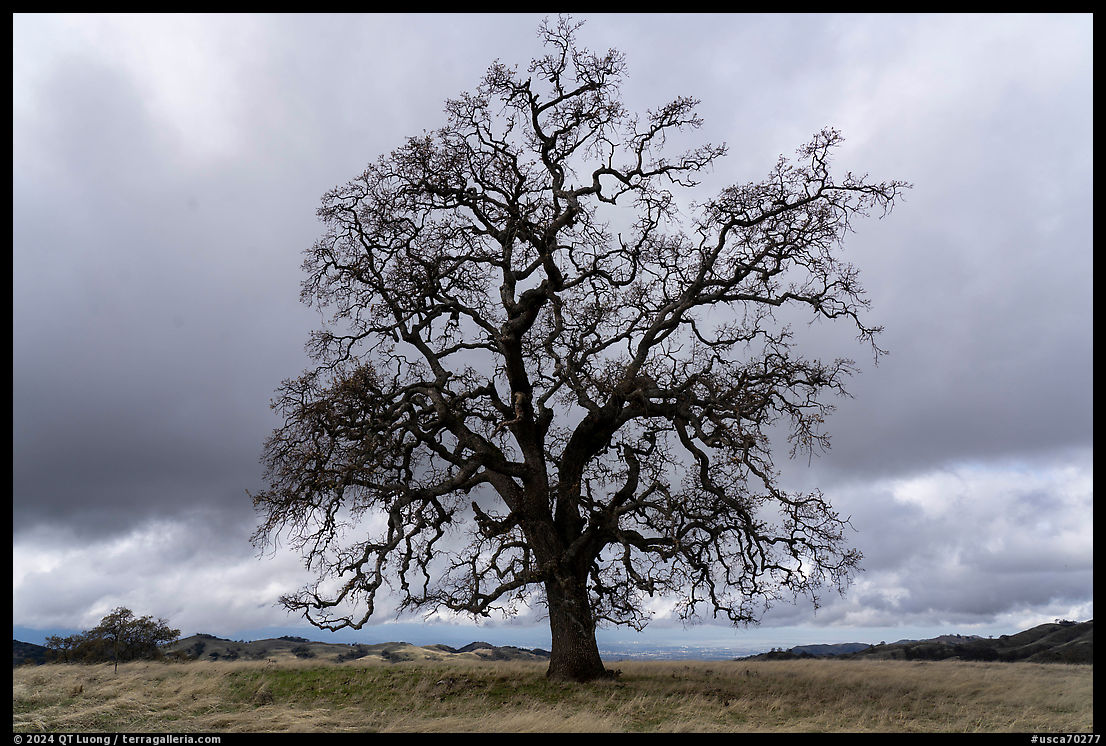

My home is in San Jose, California, the largest city in Northern California, yet two dozen nature parks lie within a half-an-hour drive. Some are reclaimed lands, while others are still leased for cattle grazing. I chose not to chase dramatic, fleeting moments of remarkable light but instead visited the trail during midday hours, reflecting the experience of most residents. By immersing myself in these ordinary conditions, I found an unexpected connection to the qualities of wilderness that persist, even in spaces adjacent to urbanized areas. Through the series Landscapes where I live (here and there), I sought to convey a sense of romantic reverence for these landscapes, capturing their beauty and spirit as they exist in everyday. Even in places where the boundaries between the wild and human-made blur, I discovered profound value in the presence of nature. This experience underscored the idea that a deep connection to the natural world is not confined to remote or pristine environments but can be felt anywhere—if one approaches with attention, sensitivity, and openness to the subtleties of the land. The Coyote Creek Trail, the longest multi-use paved trail in San Jose, runs through a narrow corridor of public land, providing a vital green space amidst urban and suburban surroundings. Initially, my approach to photographing the trail was shaped by the conventions of idealized nature landscape photography, seeking to highlight moments of pristine beauty within the environment. Over time, however, I came to recognize the trail as a lived-in landscape—one where the natural and human-made coexist and influence each other. The Trail will eventually be a black-and-white photography project, but at first I photographed in color. Those images represent a glimpse of the project’s start. The last one is not what it appears to be, hinting at an unexpected direction the project took me to. What appears to be tranquil autumn fog is smoke from a campfire set by unhoused residents.

After I finished school and began working, I stopped checking non-fiction books from the library. Instead, I used my newly available funds to buy books. I could then physically mark salient words or passages while reading. This more active approach helps me retain the material better. I continue it to this day. I was going to simply copy the sentences I had marked while reading the essay, but realized that rewriting them would be more respectful of the copyright. The 2000-word summary below results from this process. I hope that it proves as thought-provoking to you than it was for me.

Summary of The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature, by William Cronon

For countless Americans, wilderness represents the last sanctuary untouched by civilization’s relentless reach—a precious realm where the natural world endures in its purest form, essential to the survival of our planet. Yet, rather than existing apart from humanity, these lands are deeply shaped by human hands and values, born from distinct cultural moments and intentions that mark our history.

The wilderness we enter is far from a mere construct of our own. Recall the emotions stirred by moments in the wild, and you sense an undeniable presence of something wholly nonhuman, something profoundly beyond yourself. And yet, what led each of us to seek out these places, where such memories could take root, is entirely a product of human culture.

In the eighteenth century, wilderness evoked images of desolation—”deserted,” “savage,” “barren,” and ultimately “waste,” with associations far from favorable. It inspired emotions of “bewilderment” and fear, rooted deeply in biblical references. The wilderness was a place one entered reluctantly, often with a sense of dread. But by the late nineteenth century, this perception had shifted dramatically. The barren landscapes once considered devoid of value began to be seen as priceless treasures. When Thoreau proclaimed in 1862 that “Wildness is the preservation of the world,” he captured the essence of a profound transformation. By the early twentieth century, national attention turned to battles like that for Hetch Hetchy, where defenders decried the dam not as progress, but as a sacrilege—a violation of nature’s sanctity.

The roots of this remarkable shift can be traced to two main forces: the sublime and the frontier. The sublime, a profound cultural construct rooted in the Romantic movement, spans Europe and America, while the frontier embodies a uniquely American ideal. Together, these forces reshaped wilderness, embedding it with moral values and symbolic meanings that persist. The modern environmental movement is, in many ways, the inheritor of both Romantic ideals and a post-frontier worldview.

For wilderness to wield such profound influence, it had to embody the deepest values of the culture that revered it; it had to become sacred. This sense of the divine in wilderness existed even when it was considered a realm of spiritual peril—where if Satan roamed, so too might Christ. By the eighteenth century, this notion of wilderness as a supernatural threshold found form in the sublime. Thinkers like Edmund Burke, Immanuel Kant, and William Gilpin framed sublime landscapes as rare places to glimpse the divine, especially in vast, awe-inspiring terrains that stirred humility and reminded one of life’s fragility. The wonder Muir felt in Yosemite, Thoreau’s solemnity on Katahdin, and Wordsworth’s reverence in the Simplon Pass are different in tone but united in spirit, each man viewing the mountain as a cathedral. Their expressions of piety vary—Wordsworth’s bewildered awe, Thoreau’s austere solitude, Muir’s joyful ecstasy—but all share the same sacred sanctuary for their devotion.

The romantic sublime was not the only force that elevated wilderness to a sacred American ideal in the nineteenth century. Equally significant was the pull of primitivism—the belief that a simpler, more elemental way of life offered a remedy to the excesses of a refined and overly civilized society. In the United States, this idea crystallized in the national mythology of the frontier. As Frederick Jackson Turner described, easterners and European immigrants journeying to the unsettled frontier lands cast off civilization’s constraints, reawakened their primal energies, reinvented grassroots democratic institutions, and infused themselves with a vitality, independence, and inventiveness that defined American democracy and character. Wildlands became not only sites of spiritual renewal but also of national regeneration—the essential ground for understanding American identity. Yet the frontier myth carried an inherent acknowledgment of its impermanence. Within the narrative of the “vanishing frontier” lay the seeds of wilderness preservation. Safeguarding wilderness was, in a profound sense, a way to protect America’s most cherished origin myth.

A key element of the frontier myth was the conviction among some Americans that wilderness represented the final stronghold of rugged individualism. Paradoxically, the men who reaped the most from urban-industrial capitalism were often those most intent on escaping its stifling influence. For them, wilderness became the preferred landscape for elite tourism. Unlike rural people, who knew the demands of working the land, elite urban tourists and wealthy sportsmen brought their leisure-driven frontier fantasies into wild spaces, transforming wilderness into a reflection of their ideals.

The idea of wilderness as untouched, “virgin” land has always been painfully ironic from the perspective of Indigenous people who once inhabited those places. Displaced so that tourists might savor the illusion of an unspoiled America, these communities bore the burden of a manufactured wilderness experience. This forced removal underscores just how constructed the American concept of wilderness truly is. One of the clearest proofs of this invention is wilderness’s systematic erasure of its human history. In almost every form, wilderness represents a retreat from history itself.

The paradox of wilderness is that it subtly mirrors the values its admirers aim to escape. This retreat from history, nearly central to the wilderness ideal, offers the false hope of avoiding responsibility—a comforting illusion that we might erase our past and return to a pristine world untouched by human influence. Only those already distanced from the land could envision wilderness as an ideal for living in harmony with nature. The romantic wilderness ideal leaves no space for humans to make a livelihood from the land, embodying an ideology that ultimately excludes sustainable human presence.

Here lies the heart of the paradox: wilderness promotes a vision in which humanity is entirely separate from the natural world. If we insist that nature’s truest form must be wild, our presence becomes its undoing. As we live within an urban-industrial society yet imagine our true home lies in the wilderness, we subtly permit ourselves to sidestep accountability for our everyday lives. Through its escape from history, its alluring call to flee, and its reinforcement of a harmful dualism placing humans outside nature, wilderness presents a significant challenge to responsible environmentalism in modern times.

I hope it is now evident that my critique in this essay is not aimed at wild nature itself or even at the initiative to preserve large areas of wilderness. Rather, I question the specific ways of thinking that arise from this intricate cultural construct known as wilderness. The issue lies not with the landscapes we classify as wilderness—nonhuman nature and extensive natural areas certainly merit protection—but with the meanings we attach to that label. As biological diversity—and the wilderness itself—faces an uncertain future that demands careful and conscious management of the ecosystems supporting it, the wilderness ideology may stand in opposition to the very conservation efforts it advocates. Countries in the Third World grapple with significant environmental and social challenges that cannot be resolved through a cultural myth that urges us to “preserve” uninhabited landscapes, landscapes that have not existed in those regions for centuries.

In McKibben’s perspective, nature is dead, and we bear the responsibility for its demise. This view attributes a greater power to humanity than we truly possess; if nature is destined to perish because of our presence, then the only way to safeguard it would be to kill ourselves. By presenting wilderness as the ultimate hunter-gatherer antidote to civilization, Dave Foreman, the founder of Earth First!, perpetuates a stark yet familiar interpretation of the frontier primitivism myth. In this view, wilderness becomes the battleground for an epic conflict between destructive civilization and nurturing nature, rendering all other social, political, and moral issues insignificant in comparison. It is telling that these seemingly minor environmental problems disproportionately impact marginalized communities.

The dualism inherent in the concept of wilderness leads its proponents to frame its protection as a simplistic struggle between those who appreciate the nonhuman world and those who do not. This perspective risks overlooking critical distinctions among human communities and the complex cultural and historical contexts that shape varying views on wilderness. For instance, why is the “wilderness experience” frequently portrayed as a recreational pursuit primarily accessible to those with the class privileges that afford them the time and means to escape their jobs? Why does the preservation of wilderness often create a divide between urban outdoor enthusiasts and rural residents who depend on the land for their livelihoods? Moreover, why are “primitive” peoples romanticized in discussions about untouched natural areas, only to be dismissed when they engage in modern, human activities?

Romanticizing a distant wilderness often leads to neglecting the environment in which we truly reside—the landscape we inhabit, for better or worse. Many of our most pressing environmental challenges originate in our backyards, and addressing these issues requires an environmental ethic that informs us about responsible use of nature and conservation. The wilderness dualism frames any form of use as inherently abusive, which limits our ability to find a middle ground where responsible use and preservation can coexist in a balanced, sustainable manner.

My main concern with the concept of wilderness is that it can lead us to undervalue or even disdain the simpler, less celebrated places and experiences in nature. Without us fully recognizing it, wilderness often elevates certain aspects of the natural world while marginalizing others. By encouraging us to fetishize vast, awe-inspiring landscapes, these distinctly American notions of wilderness set an unrealistic benchmark for what we deem “natural,” making it easy to overlook the beauty and significance of the more ordinary environments that surround us.

One of the central tenets of my environmental ethic is the importance of recognizing that we are an integral part of the natural world, deeply connected to the ecological systems that support our lives. Any perspective that suggests a separation from nature—something wilderness often implies—can foster environmentally irresponsible behavior. At the same time, it is equally vital to acknowledge and respect nonhuman nature as a realm we did not create, possessing its own inherent, independent reasons for existence.

To bring the positive values we associate with wilderness closer to home, we must expand our understanding of the “otherness” that wilderness aims to define and protect. The myth of wilderness suggests that we can traverse nature without leaving a trace. However, living within history means we inevitably leave marks on a world that has already fallen. Our challenge lies in determining what kind of marks we choose to make. This is where our cultural narratives about wilderness are particularly significant. In the broadest sense, wilderness invites us to consider whether the Other must always yield to our desires and, if not, under what conditions it should be allowed to thrive without our interference.

The profound allure of the wild lies in the fact that wonder in its presence requires no effort; it simply overwhelms us. Wilderness becomes problematic only when we mistakenly believe that this sense of awe and otherness is confined to remote areas or relies on untouched landscapes far from our everyday lives. By recognizing the otherness in what feels unfamiliar, we can begin to appreciate it in what initially appears ordinary.

Our task is to move beyond rigid moral binaries— human versus nonhuman, natural versus unnatural, or fallen versus unfallen—that shape our understanding of the world. Instead, we should embrace a more nuanced continuum of natural landscapes that includes urban, suburban, pastoral, and wild spaces, each deserving of recognition and celebration without disparaging the others. We must honor the Other within our communities and the Other next door just as much as we cherish the distant, exotic Other.

Embracing a place as home inherently involves engaging with the nature present in it; there’s no escaping the need to manipulate, cultivate, or even harm certain aspects of nature to create our living spaces. However, if we recognize the autonomy and otherness of the beings and ecosystems around us—what our culture often labels as “wild”—we will be compelled to think more critically about how we interact with them and to question whether we should exploit them at all.