Lake Clark National Park is the third less visited of America’s 59 National Parks. Lack of road access may contribute to that. My summer visit used a chartered floatplane to travel into the

park’s backcountry. On a recent 2.5-day visit aimed at seeing some of the park in the autumn, I limited explorations to the immediate area surrounding Port Alsworth. Find out how despite the town being the largest and most easily reached community within the park, you can have a quick and excellent wilderness experience nearby.

Traveling to the park

Flying anywhere else into the park requires a charter plane, but Port Alsworth is a large enough community (population 159) to be serviced by regularly scheduled flights from Anchorage, which are more affordable than charter flights – as of 2016, the cost was $540/person round-trip. That would be our only expenses in the park. The arrival in Port Alsworth disconcerts, as you land on an unpaved airstrip next to a hangar. However, a walk along the runaway (watch for planes!) brings you soon enough to the familiar sight of a national park’s visitor center. Together with the adjacent historic exhibit, it is the only facility in the park operated by the National Park Service, and they besides information, they will provide you with free bear canisters loans, which are mandatory for camping in the backcountry.

Accomodation

Unlike national parks in the continental U.S., many Alaskan national parks include private in-holdings, which means private lands surrounded by public lands. Much of the lands around Lake Clark are private,

including Port Alsworth. Half-a-dozen private lodges offer comfortable stays – at a cost typical of Alaska, and there is a private campground within walking distance from the airstrip. The sites cost $50/night, however, they include tent enclosures with clear roofs and mosquito netting for walls, as well as firewood, potable water, and showers. If you ask your air service, they will point you to a spot next to the runway where you could pitch your tent for free, but backcountry camping provides a much nicer experience.

Lake Clark

There isn’t much to see in Port Alsworth since all the lands are private. The only access to Lake Clark is via an easement (a trail with public access on otherwise private land) situated at the West end of the north airstrip, the one located closest to the lake. It leads to a pebble beach next to a stream where you may see salmon. Other than that, to explore Lake Clark, you’d need to rent a watercraft from an outfitter. Kayaks and motorboats are available. Past the General Store, located towards the East end of the south airstrip, you will find the trailhead for the only maintained trail system in the park.

Tanalian Falls Trail

The 5-mile round-trip (300-foot elevation gain) trail to Tanalian Falls passes tundra meadows, birch groves, and beaver ponds frequented by moose and waterfowl along the lower Beaver Pond Loop. On the way back, you can take the other branch of the loop, called the Falls and Lake Trail for a higher view. Although the trail is mostly forested, on a rainy day, I found an opening between the trees for a layered composition including beaver ponds and Lake Clark.

The falls are fed partly by runoff, so they are most robust in early summer. They are only about 50 feet, but quite wide and dramatic. The view from the base, reached by a short spur trail, includes the sky, so it works best when the falls are well lit, which is in the afternoon, as they are west-facing. For a different perspective, you can walk the other spur trail to the brink of the falls.

Kontrashibuna Lake

By hiking another mile round-trip from the falls, you’ll reach beautiful Kontrashibuna Lake. It is smaller than Lake Clark and offers compositions with mountains situated at a closer distance. A trail hugs the north shore of the lake. After hiking in steady rain, I was elated that the clouds broke for a short instant. But after a quick photo, I had to rush to take opportunity of the dry moment to pitch my tent because I knew the rain would return soon.

The Kontrashibuna lakeshore features the best backcountry campsites around Port Alsworth, and the closest one was even equiped with a bench and a campfire spot nearly next to the water. There are a few canoes there too, but they belong to the Port Alsworth community and are not for public use. The site lies only slightly more than 3 miles from Port Alsworth, yet you will feel you are camping in the wilderness, save for the occasional sounds of air traffic.

Tanalian Mountain Trail

If you are ready for a strenuous hike, from the junction with the Beaver Pond Loop, the Tanalian Mountain Trail is 4.8 miles round-trip with a steep 3,250-foot elevation gain. It starts in a lovely deciduous forest. The autumn color display was superb at the end of the second week of September.

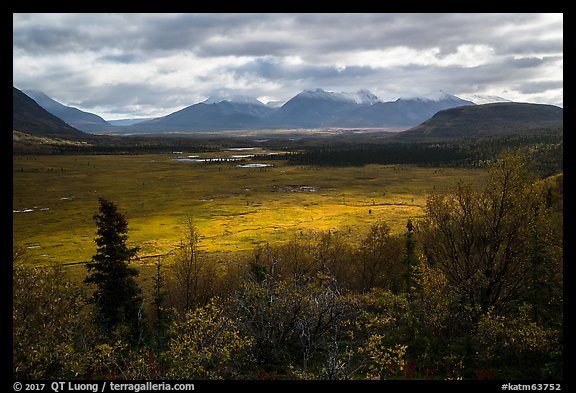

From the mid-point of the trail up to the top, the trail gets more faint, as the forest gives way to tundra, which also turns shades of gold and crimson in autumn. On one side, fantastic views open over fifty-mile long Lake Clark. Port Alsworth and Tanalian Mountain are situated approximately in the midway the Lake Clark, and this is the view looking Northeast.

On the other side, the views are over serpentine Kontrashibuna Lake and its turquoise-colored waters. Having such a high viewpoint gave me a different perspective on the park that I didn’t even get during my previous week-long backpacking trip during which we did not hike up mountains – upon returning to the civilization of Port Alsworth, we did not feel like tackling one and turned around at the falls.

The narrow summit offered a fantastic 360-degrees view, with a glimpse of the active Iliamna Volcano in the distance. I lingered on Tanalian Mountain until one hour before sunset so that I would reach timberline just at sunset time.

I was happy that for the first time in more than a week, the sky was clear enough to let in a golden glow over Lake Clark that I photographed looking Southwest before going back to the woods.

Descending in the forest by night, I needed to be careful not to lose the lightly used trail, getting back to camp around 11pm, after a few night photographs on the way. Since the instant we set camp for two nights to the time we broke the camp, we didn’t see a single other person, and that included our time on the trail during the day. It would have been easy to hike the same trails starting from Port Alsworth, but camping by the lake elevated the experience to make it one of my most satisfying two-day trips.

More photos of Lake Clark National Park

Autumn in Alaska: Part 6 of 9:

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

8

|

9

Installation in progress, May 22

Installation in progress, May 22

Installation in progress, May 23

Installation in progress, May 23