Experiments in Image Memorability Computation

The Tunnel View set

As a former Artificial Intelligence (AI) scientist turned full-time photographer, I enjoy keeping an eye on latest advances of AI being applied to photography. Photo editing is an elusive skill, with excellent professional photo editors commanding three-figure hourly rates. So when I ran across an article reporting on new technology that may automate “choosing the best photos”, my curiosity was picked.As a quick test, I ran the algorithm on a set of 8 photographs made at Yosemite’s Tunnel View, with those resulting scores:

Although all the scores were relatively low (more on that latter), I was impressed to see that the algorithm scored my well-known image the highest. Could it be that indeed it is now possible to automatically pick up the best image ?

The terragalleria.com image library

I was intrigued enough with that quick test to run the algorithm on my entire online image library of more than 37,000 images. Here are the results for all images sorted from high score to low score.Although the headline that got me curious talked about the “best” photo, anyone with a modest science training can understand that there is no such a thing. One has to first define the criteria for any metric to make sense. The criterion used by the MIT researchers for their project is “Memorability”, which they define as the ability of human observers to remember that they have seen a given picture before. As such, they are able to measure memorability by showing a large number of images to subjects (paid through Amazon Mechanical Turk) and asking them to click a button if they see an image for a second time. Once this metric is established, and the dataset gathered, they are able to use machine learning methods to produce an algorithm that achieves near human performance on that dataset.

On my dataset, textured images with strong repeating shapes seem to be overly favored. Aditya Khosla, the lead author, provided this explanation: “those might have a high score because of a limitation of our data which does not contain a significant proportion of such images. The reason is that it’s likely to find certain patterns correlated with memorability e.g., circles, but since most of the images the model has seen only contains one or two circles, it may not realize that 50 circles (as in a texture) also exist in the world and the score just keeps adding as more circles show up.”.

Besides this glitch, the results square well with a fact that has been known by psychologists for a while: the most memorable images are portraits and images of people, whereas landscape are the least memorable, as you can see by browsing results in reverse order.

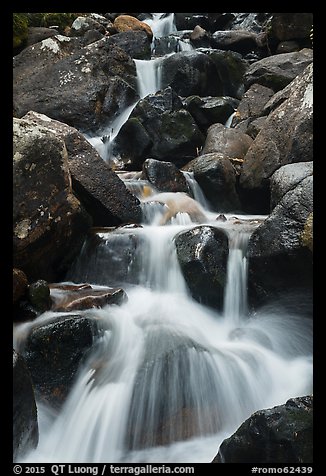

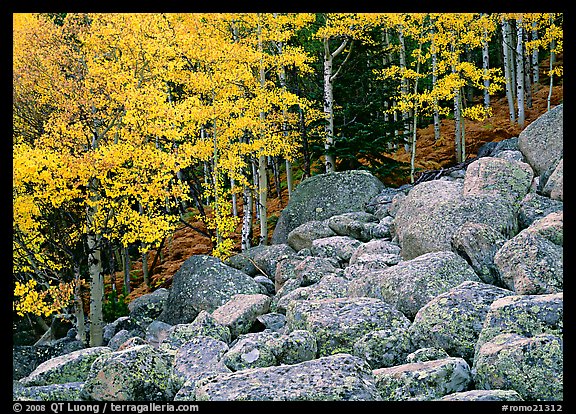

Landscapes

Now that we know that some subjects are more memorable than others, can we find interesting conclusions by restricting our evaluation to a single subject ? Here are the results for the landscape images sorted from high score to low score. Besides the bias for strongly textured images already noticed, we can see that the most memorable images are those which are “graphic”, with strong features, whereas the least memorable images are “busy” landscapes with lots of fine detail. This seems to correlate well with the observation that the former images have more “impact”.

Memorability versus Esthetics

Memorability as defined above does not correspond to the everyday definition of what makes a photo the “best”. Although the latter judgement is largely subjective, there is a whole cottage industry (photo contests), and a lot of community websites (such as Flickr or 500px) which are premised on the validity or usefulness of image ratings. For years, terragalleria.com has also been offering to visitors the opportunity to rate images, as well as sort images by those ratings. Presumably, they are based on esthetic appeal.For each of the 15,000+ images that have received at least 5 ratings from visitors, I took the average of those ratings. Users can rate images from from 10 (best) to 0 (worse). Here is the scatter plot of average ratings (X-axis) versus memorability scores (Y-axis).

If there was a high correlation between ratings and memorability, the points on the plot would be distributed along a diagonal line. As can be seen, the points are all over the place, which means that correlation is low, consistent with Fig. 4(d) in the authors paper.

Those quick experiments have not even addressed the issue of context, which plays a crucial role in how photographs are perceived and remembered – if you have any doubt, think about photojournalism. While memorability represents a promising measurement of the utility of images, photo editors jobs are still secure!