Year 2013 in review and parks night favorites

This year, I solidified my efforts into motion and multi-media, releasing my first finished time-lapse video: Hawaii Volcanoes (146K views on Vimeo), as well as 360×180 virtual reality panoramas of the Colorado Plateau.

In photography, I’ve been continuing my multivariate interpretation of the National Parks. Although I release images in large blocks based on geography, if you’ve looked carefully, you may have noticed a number of themes and sub-series. I’ll introduce more in 2014, but for this end-of-year post, I’ll highlight one: the night.

I feel that by this year, I’ve learned enough to feel as comfortable with the camera at that time as during the day. Maybe it is a carryover from my mountaineering days, but I also found myself enjoying hiking by night. With many National Park locations getting more frequented by photographers, the solitude and quiet of the night restores some of the sense of awe that I experienced during my initial visits.

Links point to blog entries where you can see more (daytime !) images and often read in great detail about my experiences while making them. For images only, see growing collection of night photographs of the National Parks.

On January 10th, president Obama signed the law renaming Pinnacles Monument as Pinnacles National Park. The next day, I made my first of several visits there. In the course of 2013 I hiked all the trails of the 59th US National Park except for one, capturing winter frost, spring wildflowers, the summer Perseid Meteor shower (pictured here), and fall colors.

In February, I returned to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park which I explored from sea to summit, photographing the Lava Ocean Entry – which was outside the Park proper in years past – and then hiking to Mauna Loa summit where I camped overnight for some unique images – my most memorable wilderness adventure of the year despite its brief duration.

Beginning April, lured by news of the best Joshua Tree bloom in living memory, I drove to Southern California to visit Joshua Tree National Park, Mojave National Preserve, and Lee Flat in Death Valley National Park. At the end of the month, after attending the inaugural edition of Paris Photo Los Angeles, I spent a few days in the foothills of Sequoia National Park, an area overlooked by most in favor of the sequoia groves and High Sierra peaks.

In June/July, I traveled to the Dakotas, spending time in Wind Cave National Park, the less visited Sage Creek and South Unit sections of Badlands National Park (but still missing Palmer Creek due to insufficient research and imprecise information from rangers), and paying respects to Theodore Roosevelt at his remote Elkhorn Ranch.

The morning before flying home, I hiked to Chasm Lake, one of the most spectacular sites in Rocky Mountain National Park, arriving barely in time to make this photograph despite waking up at 1am.

In July/August, for the first time, I went to the Florida Everglades in summer with also two days at Biscayne National Park. Despite the discomfort of heat, humidity, and mosquitoes, I was most pleased with the photographic conditions: the spectacular skies, storms, reflections, and lushness.

On that same trip, I spent three very busy days on tiny Dry Tortugas, where besides photographing by night, and underwater (not at the same time), I set foot on Loggerhead Key thanks to friendly and generous sailors who spared me the risky open-sea crossing.

In mid-September, I caught one of the last trips of the year to Wizard Island in Crater Lake National Park, finding that the six hours between drop-off and pick-up were barely enough to explore.

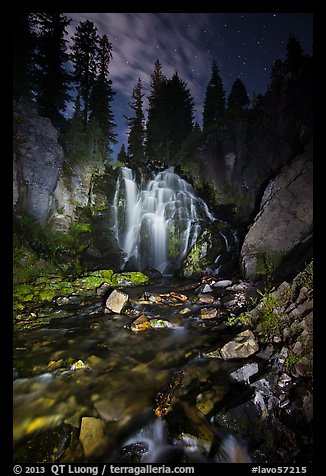

Driving from Crater Lake, I arrived at Kings Creek Fall in Lassen Volcanic National Park without daylight left because the shorter trail was closed. I got the shot by light-painting using the bright torch I was carrying in addition to my headlamp. On the next days, I visited Juniper Lake and Warner Valley, quietest sections of one of the least visited National Park.

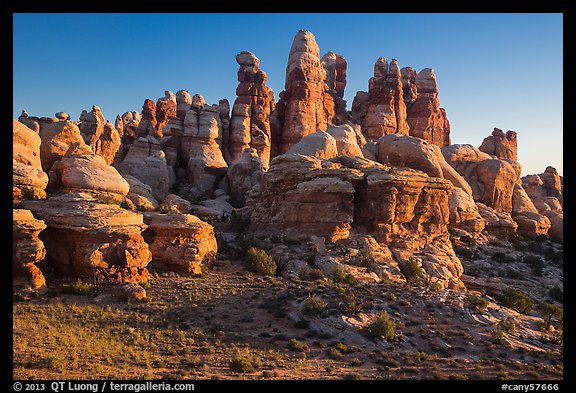

In October, I led a rare photo tour into the Maze of Canyonlands National Park, during which we enjoyed great scenery, adventure, isolation, food, and camaraderie.

After the tour, I stayed in Utah for a week, revisiting Capitol Reef National Park and Arches National Park. In the small and popular park, I found solitude and out-of-the-beaten path locations in the Courthouse Wash, the ridge beyond Delicate Arch Viewpoint, and at Cove Arch (picture).

As you seen through this short selection which I hope will inspire you for 2014, nighttime brings in a host of possibilities not available during the day. Besides the change in illumination angle of the moon (equivalent to time of day, main variable in daytime photography), there is also the moon phase, and the opportunity to light the scene, either with fixed lights or light painting. Then there is the glorious night sky with stars, planets, and the Milky Way.

I am concluding this overview of the year by expressing my gratitude to you, my audience. I hope that you had as good a year than I had, and wish you an even better year 2014 !