This article features a supremely diverse mix of ten lesser-visited national parks all around the country. They all offer fantastic scenery and are almost sure to provide you with the quiet experience that you hoped for when you headed to a national park.

Having spent more than a quarter century photographing each of the 63 U.S. national parks, I particularly cherished my visits to the parks less traveled. My book Treasured Lands: A Photography Odyssey through America’s National Parks aimed to illustrate and describe in detail not only the better-known parks but also the less-visited hidden gems. Based on my experience, here are ten parks without crowds presented in decreasing order of visitation.

1. Capitol Reef National Park, Utah.

Colorado Plateau region, 1,230,000 visits in 2022

Among the cornucopia of natural environments found on the American continent, maybe the most unusual are those of the Colorado Plateau, where a convergence of geology and climate has created landscapes without equal anywhere else. Capitol Reef National Park is less known than its neighboors in the region , yet it offers a variety of rock formations that rival any other national park of the Colorado Plateau. Sheer monoliths, domes, canyons, and arches highlight the Waterpocket Fold, a 100-mile-long wrinkle on the earth’s crust. The opportunity for solitude in addition to the variety of landscapes makes Capitol Reef one of my favorite national parks.

Temples of the Moon and of the Sun, Cathedral Valley. Capitol Reef National Park

Most visitors stay on UT 24 and the scenic drive. They cover only a tiny portion of the park but still offer great diversity and a relatively uncrowded experience. Venture on the extensive network of dirt roads south or north of UT 24, and you’ll fully appreciate what the park has to offer. You will make fantastic discoveries, as both the southern and northern sections of the park would have been deserving of national park status by themselves. You will see only a few souls during the whole day. To access locations such as the majestic Cathedral Valley with striking monoliths or the Strike Valley and Hall Creek overlooks, you have to be willing to leave the pavement, but in normal conditions, you don’t need a particularly rugged vehicle.

Thanks to the Fremont River, the park has more vegetation than other neighboring parks and makes a spring or fall visit particularly rewarding. Fruit trees growing in historic orchards bloom from March to May. Autumn foliage color peaks during the last week of October. Hot summers and cold winters bring their own opportunities, such as monsoon clouds and snow, but are not the best seasons for exploring outside of the pavement, as melting snow and summer thunderstorms can turn dirt roads into impassable mud.

2. Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota

Rockies and Prairie region, 660,000 visits in 2022

In Theodore Roosevelt National Park it is easy to experience the isolation of the badlands much the same way that Theodore Roosevelt had more than a hundred years ago. What the North Dakota badlands lack in starkness compared with the better-known Badlands National Park in Southern Dakota is more than made up by a more rugged character, abundant wildlife and vegetation, and the flow of the Little Missouri River. In addition, you will find rare geological phenomena, such that cannonball concretions, caprock hoodoos, and petrified wood.

Grasslands and badlands, Painted Canyon. Theodore Roosevelt National Park

The park comprises two main units. The South Unit is the largest, most developed, and most visited, and it has more varied landscapes, more trails, and more wildlife. Bison and prairie dogs live in both the south and north sections, but only the South Unit features roadside prairie dog towns and roaming wild horses. In addition to the 36-mile scenic loop inside the South Unit, there is an excellent overlook at Painted Canyon Visitor Center right off I-94 from which a wide range of compositions are possible. The North Unit, which is 70 miles from the South Unit and has a 14-mile scenic drive, is more scenic, wild, and quiet, with only 10 percent of the park’s visitation. Most of the areas of interest are roadside or accessible through short hikes.

Winters are very cold. In early spring, the grass is bleached, but by mid-May, it has greened up and wildflowers begin to appear, lasting into July in the prairie flats and river valleys. Thunderstorms create great skies in the summer. Late September brings autumn foliage to the aspen and cottonwoods lining the banks of the Little Missouri River.

3. Big Bend National Park, Texas

Desert region, 514,000 visits in 2022

Lying 325 miles from El Paso, TX, the closest major city, Big Bend National Park is one of the most remote and least-visited parks in the continental U.S. The three roads leading to the park do not pass through any other location. Your destination, should you drive in that direction, can only be the vast national park, one of the largest (1,250 square miles). Due to its size, maybe except during spring break, the park feels uncrowded even if you stay on the 100 miles of paved roads. A high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicle allows you to explore the large network of primitive and isolated roads.

Agaves on South Rim, morning. Big Bend National Park

Photographers will find easy-to-access and beautiful landscapes encompassing three distinct environments: the deep canyons of the Rio Grande River such as Santa Elena Canyon, the desert, and the Chisos Mountains. That compact mountain range, the southernmost in the U.S., can be captured rising from the surrounding desert but is also penetrated by a road that leads to the Chisos Basin. The South Rim, my prefered hike for superlative views anchored by the park’s iconic agaves, starts from there.

The park’s varied topography supports beautiful flora. While something blooms in almost every season, annual wildflowers are most abundant in February and March, whereas cacti start blooming in April, usually peaking in late May. You will also find more diverse wildlife than you’d expect in such arid terrain, including more species of birds (around 350) than in any other national park. Temperatures are most pleasant from late fall to early spring, with a dusting of snow possible in the winter on the high peaks. Late spring to early fall brings temperatures above 100°F to the desert, igniting frequent dramatic thunderstorms. Most of the accommodations and park activities are in the Chisos Basin, which is cooler than the desert.

4. Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska

Alaska region, 453,000 visits in 2022

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve is a vast roadless marine wilderness dominated by tall coastal mountains. There are trails at Bartlett Cove, but the park’s highlight is to observe close some of the fifteen large tidewater glaciers calving icebergs into the water, about 50 miles up the bay. In addition to the abundant wildlife typical of Alaska, the park is home to spectacular marine life. The vast majority of visitors to Glacier Bay see the park from the high deck of a cruise ship. This accounts for the park’s relatively high visitation number for Alaska, but those passengers do not actually set foot in the park. A smaller, concessionaire-operated tour boat, departs daily during summer months from Bartlett Cove and offers a day-long tour covering 130 miles for whale watching, photography, and wildlife viewing. Although this boat can drop off and pick up backcountry kayakers, it does not offer landings to day trippers. Both types of vessels visit tidewaters glaciers such as Margerie Glacier.

Terminal front of Margerie Glacier. Glacier Bay National Park

There are two ways to land: by kayak or small charter boat. Either of them will provide you total solitude beside the occasional vessel in the distance, and access to places that very few have seen close. My two favorites were Mc Bride Glacier and Lamplugh Glacier. Kayaking the bay is a tough trip: the marine environment of the bay is extremely dynamic, with wet weather and ice-cold water. Some of the highest tides plus strongest tidal currents I’ve seen anywhere, rising and falling up to 25 feet, require careful planning. Multi-day trips are required to reach the glaciers. Typically for Alaska, charter boats are expensive. However, in a few days aboard one of them, I saw more glaciers than during my whole previous two-week expedition on a kayak, while traveling in comfort—I didn’t even need to bring a water bottle.

The visitor season lasts from mid-May to mid-September, when services are available at Bartlett Cove, the main hub of the park. May and June are the least-rainy months, then precipitation increases, leading to rainy weather in late August and September.

5. Congaree National Park, South Carolina

Southeastern Hardwoods region, 204,000 visits in 2022

Congaree National Park preserves the largest remaining old-growth bottomland forest in North America. This little-visited park combines the watery environment of the Everglades with the towering old-growth forests of the West. Congaree is frequently ranked as one of the “worse” national parks. While it does lack the diversity and appeal of better-known parks, its unique environment is very rewarding for a short visit.

Bald cypress and tupelo in summer. Congaree National Park

The park is a small 41 square miles, but you cannot explore it by driving. Hiking and canoeing are the only ways to immerse yourself in the forest. Starting from the visitor center, the flat, easy 2.4-mile Boardwalk Loop Trail is a good introduction to the park, offering diverse perspectives and natural environments. Water floods the forest about ten times per year, creating opportunities to photograph beautiful reflections. However, even if you come when the forest isn’t flooded, you can still find water in creeks and lakes. In dry conditions, my favorite spot along the Boardwalk Loop is Weston Lake, an abandoned channel of the Congaree River where I photographed trees growing out of the water, emblematic of the South. The most memorable experience in the park was riding a canoe through a narrow channel beneath a canopy of trees on Cedar Creek. As with the Everglades, exploring via water provides you with a unique perspective.

The environment is mostly a deciduous forest with no distant views, most easily photographed in cloudy conditions. In the early spring, you are more likely to find the forest flooded. The most beautiful time to visit is in late autumn when the foliage turns various shades of yellow and red. In the winter the trees are bare. Spring and fall are the most comfortable seasons, as summers are hot and humid and bring lots of mosquitoes.

6. Great Basin National Park, Nevada

Basin region, 142,100 visits in 2022

Accessed by way of Hwy 50, “the loneliest road in America” in the middle of the American West (some would say in the middle of nowhere), Great Basin National Park is one of the least-visited national parks. Even when crowds fill the Southern Utah and California national parks, midway between them, Great Basin remains quiet. It is not because of the lack of attractions. I cannot think of any other national park that offers a more intriguing mix of natural wonders: a cave with rare formations, a peak with one of the most southerly glaciers, bristlecone pines and aspen growing nearby, the six-story limestone Lexington Arch.

Bristelecone pines on Mt Washington. Great Basin National Park

Most visits take place along the only paved road in the park, the 12-mile Wheeler Peak Scenic Drive. It passes by the visitor center under which Lehman Caves are situated and ends at 10,000 feet, at the trailhead for the best hikes in the park. However, if the main section of the park is not quiet enough, there are also five unpaved roads that lead to remote valleys and to Washington Peak, where I found the most beautiful bristlecone pine grove in the park, set against great views. Most of the attractions can be reached by moderate day hikes

Tours of Lehman Cave take place year-round. Snow closes the upper 8 miles of the Wheeler Peak Scenic Drive from November to May. Summer is a pleasant time to hike the high trails, which enjoy moderate temperatures while the desert below simmers. Aspen groves on the upper slopes of the park are at the peak of their autumn color in late September.

7. Dry Tortugas National Park, Florida

Tropics region, 78,500 visits in 2022

Few people visit Dry Tortugas National Park because of its remote location, yet it is a unique place with a powerful surrealistic appeal. An unexpected huge historic fort tops some of the most beautiful coral reefs and beaches in the United States. Fewer people yet camp on the island, which I felt was a wonderful experience.

Bush Key with conch shell and beached seaweed. Dry Tortugas National Park

The ferry trips starting from Key West take 3 hours each way, arriving around 10.30 AM and leaving at 2:45 PM. While by the numbers Dry Tortugas is the third least visited national park in the continental U.S., the 200 daily visitors are quite noticeable on the tiny Garden Key. Bush Key always remains serene but is sometimes closed for nesting birds. However, by midafternoon, the day-trippers are gone. You then share the island with at most two dozen campers.

An overnight stay may seem unnecessary, considering the tiny size of the island, but there is much more to discover than it appears at first, especially if you are equipped for water activities. With its warm and clear water and abundant marine life, it is as good a place as any to try your hand at underwater photography at midday. In the late afternoon, when the light is less favorable for underwater photography, you can photograph a deserted fort without harsh sun. Besides ample time, sunset, sunrise, and night photography opportunities, you get to witness the daily cycles of life on the island, such as thousands of colorful hermit crabs of all sizes and shapes crawling all over the place, including up the trees, in the summer evenings. A bit of planning is necessary since camping there is primitive and everything you need, in particular, food and water, has to be brought.

8. North Cascades National Park, Washington

Pacific region, 30,200 visits in 2022

Deserving of being called America’s Alps for steepness and glaciation, North Cascades National Park preserves some of America’s finest mountain landscapes, The park is also only three hours from Seattle, yet it is one of the least-visited parks in the lower 48 states, second only to remote and roadless Isle Royale National Park. This is because North Cascades National Park proper is managed as a wilderness without facilities and almost no road access, accessible only to hikers, backpackers, and mountaineers. Cascade Pass enlived by wildflowers in summer and Easy Pass brightened by golden larches in autum are two favorite and contrasting access points to the park’s high country.

Colonial Peak and Pyramid Peak above Diablo Lake on rainy evening, North Cascades National Park Service Complex

However, If you are not ready to climb over those strenuous passes, you can still find excellent views from lower, more developed and accessible areas adjacent to the park. Most of them are part of the larger North Cascades National Park Service Complex, which also includes the Ross Lake National Recreation Area (863,000 visits) and Lake Chelan National Recreation Area (37,600 visits). The most iconic view in the whole range is found at roadside Picture Lake, located in the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest. The North Cascades Highway (SR 20) is considered by some to be the most scenic mountain drive in Washington. It runs through the Ross Lake National Recreation Area, providing access to roadside views of reservoir lakes such as Diablo Lake surrounded by mountain peaks, often made more evocative by low mist.

That far north, summer is very short. At higher elevations, trails are free of snow only from July to September. Wildflowers peak in the valleys in May, but in alpine areas, not until late July. Most fall colors start one month later, lasting into October. The first winter snows (usually early November) close SR 20 until April.

9. Isle Royale National Park, Michigan

Southeastern Hardwoods region, 25,500 visits in 2022

Isle Royale National Park, situated in the northwest corner of Lake Superior, is defined by its isolation. The island is only accessible by a lengthy boat crossing and consists of a roadless backcountry. The least-visited national park in the continental United States, Isle Royale National Park receives fewer visitors in a year than Yosemite does on a summer day. The few who make it there take the time to soak in this North Woods wilderness fringed by a beautiful shoreline, where moose sightings are not uncommon. Visitors there stay on average for three and a half days, while the average visitor to a national park stays for just 4 hours.

Bull moose in summer forest. Isle Royale National Park

The two areas with facilities, Windigo and Rock Harbor, are situated at either end of the island. They are about 45 miles apart by trail, and it takes 5 hours to link them via the Voyageur II, which circles the island. Public ferries and seaplanes service the park, and your itinerary will dictate the best one to use. A day visit is possible, but I do not recommend it. Day visitors must hurry for a few hours of sightseeing in mid-day light, much less than the time they spend on the boat. Overnight backpacking or kayaking trips truly unlock the island. However, day hikes can also be satisfying. Rock Harbor is the more scenic and developed of the two main areas, with the only lodge on the island. From there, you can go on day hikes, take sightseeing tours on the M/V Sandy, or rent motorized and nonmotorized boats. The Voyageur II makes a number of stops mid-island, at docks close to campsites. After a drop-off, you could set up camp close to the dock and explore the surroundings on day hikes or with a kayak, which can be transported by the Voyageur II.

Isle Royale is the only national park with an annual closure. Boat transportation is only available from May to early October. In June and July, wildflowers peak, but so do swarms of biting insects. July and August are the peak months, and the only time when the facilities are fully available. Late September, my favorite time to visit, brings with it the fall colors.

10. Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, Alaska

Alaska region, 16,400 visits in 2022

Lake Clark National Park, situated on the Alaska Peninsula, preserves a supremely varied and beautiful wilderness with all the geographical features of Alaska concentrated in a relatively small area. Due to their remoteness, Alaska’s national parks are among the least visited in the country. Maybe because of the lack of famous features, Lake Clark National Park is one of the least-visited in Alaska, despite its relative ease of access. It is in Anchorage’s “backyard,” about an hour away by a small plane.

Valley between Turquoise Lake and Twin Lakes. Lake Clark National Park

Scheduled flights link Anchorage to Port Alsworth, home to most of the park’s amenities, including several private lodges. Even though there are only a few trails from there, I didn’t encounter any other hiking parties on them. Those trails give access to diverse scenery, ranging from the wide Tanalian Falls, wild Kontrashibuna Lake shore, and expansive views from the top of Tanalian Mountain. However, the park’s backcountry is even more spectacular. The area northwest of Lake Clark offers excellent hiking on a plateau above the tree line where you can easily map your own route in the tundra between Turquoise Lake, Twin Lakes, and Telaquana Lake. Using a charter flight, you can either set up a base camp and go for day hikes or backpack from lake to lake.

The park transitions into summer at the beginning of June. Fall colors appear in the first week of September at higher elevations and last until the end of the month, with new snow covering the peaks by mid-September.

An almost identical version of this article was previously published in final issue of Outdoor Photographer Magazine (June/July 2023).

Freelance magazine contracts usually are non-exclusive and based on right of first publication, which means that the author retains ownership but cannot publish materials before the magazine does. Although re-publication is not prohibited, in the past, I have refrained from it, considering it bad form. However, since the magazine is ceasing publication and its website

outdoorphotographer.com

went dark yesterday, I thought releasing the article here was fair game. If you are missing Outdoor Photographer, this blog’s archive contains a lot of long-form contents worthy of the magazine, see for instance few selected blog highlights.

The magazine version of this article included six general tips for avoiding the crowds. However, it extended for 32 pages, which is getting a bit long for a blog post which already exceeds 3,000 words. Instead, I will write an expanded version of those tips in a separate article. Stay tuned!

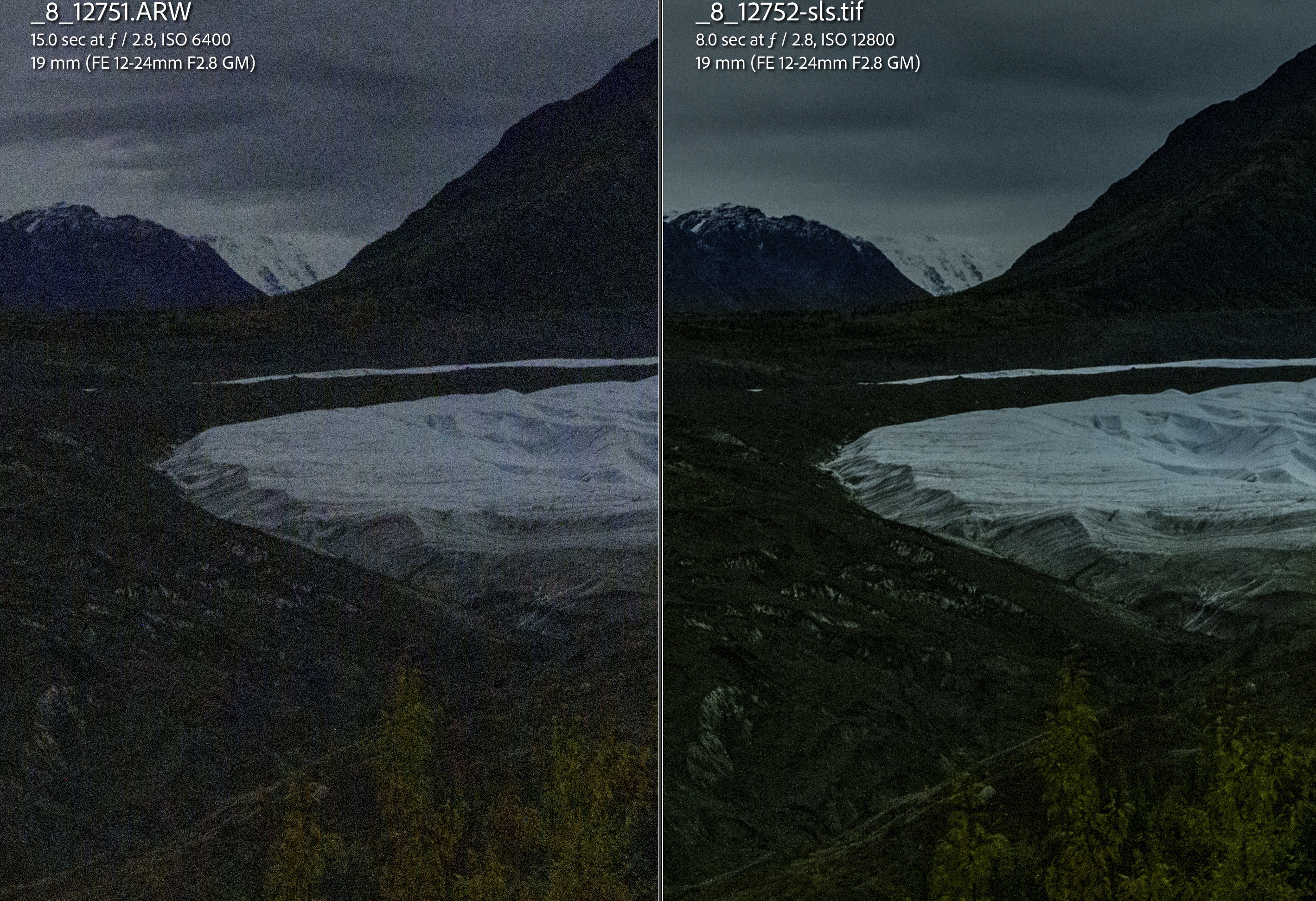

Voyageurs National Park, Minnesota (original color capture)

Voyageurs National Park, Minnesota (original color capture)