QT Luong’s Work in the USA Expo Pavilion

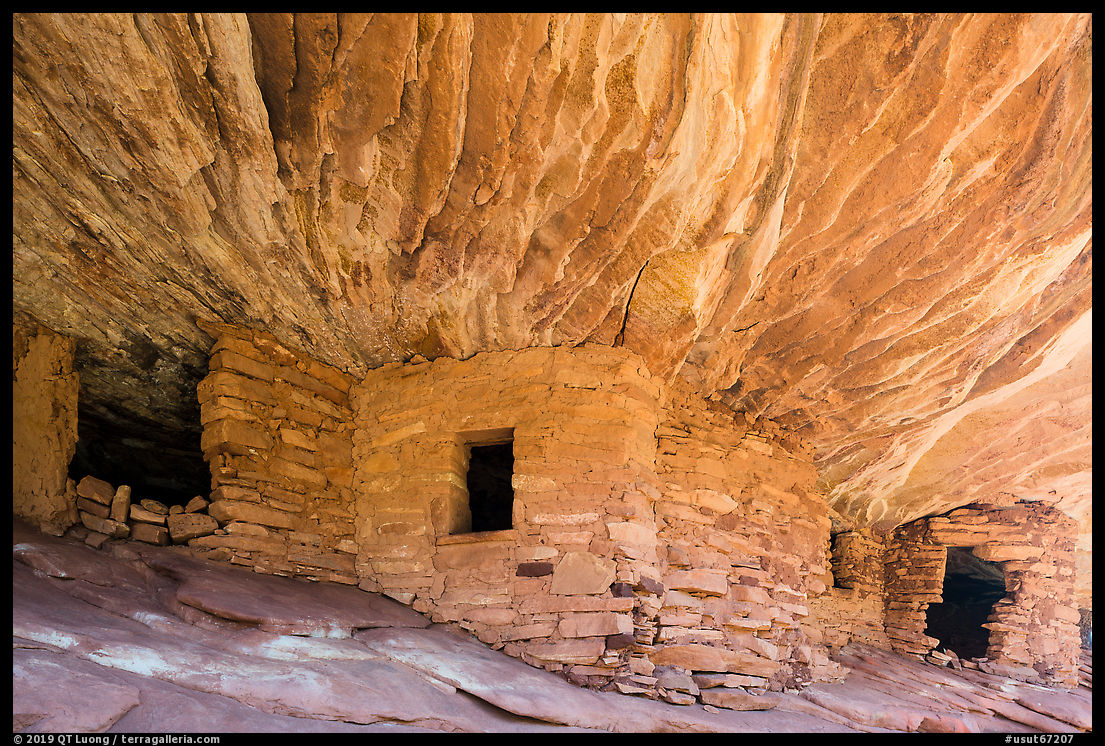

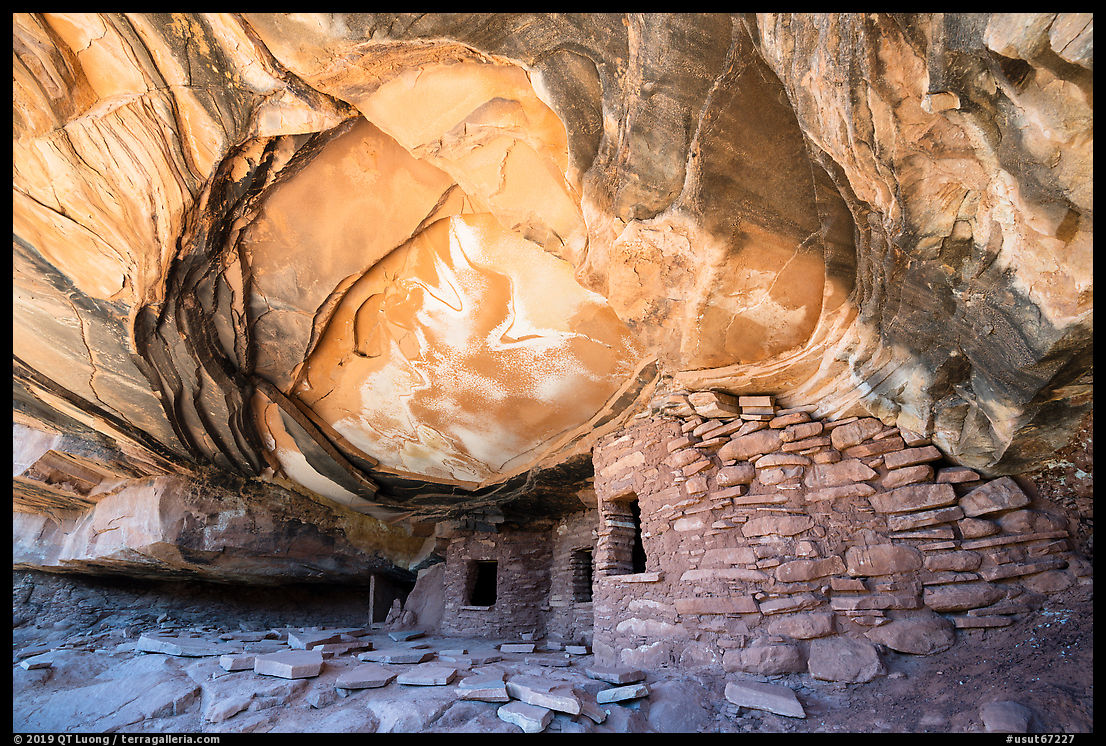

Exhibit 5 (“America the Beautiful”) may appear at odds with the rest of a pavilion that emphasizes American innovations until you remember that national parks were also a most consequential American innovation.

Thomas Jefferson’s personal copy of the Quran was one of the pavilion’s special artifacts. I learned during a Expo 2020 lecture by scholar Andrew O’Shaughnessy that America’s Founding Father and third President, a talented self-taught architect, was fascinated by octagons and built a house based on an octagonal plan at Poplar Forest. That house was an inspiration for the room housing the mural-size panels that form the exhibit. I believe the previous entry depicted that exhibit as well as I could do with four photographs. However, capturing the entirety of such a space with regular photography is challenging, as a super-wide-angle lens (the opening image was photographed at 13mm) introduces wild distortions, yet includes only a small portion of the space. Because the center of the space is occupied by the elevator, no viewpoint conveys that the octagon has equal sides. With this caveat, here is another attempt to depict the space using non-planar projections:

At the center of the pavilion, the room serves as a transition space between the first floor and the second floor. Since the room is two-story-tall and the panels fit each of the equal octagonal sides, five of them are cropped to a banner-like aspect ratio of 2.5: 13 feet wide (4m) by 33 feet tall (10m). They feel well-proportioned because the ratio between the room’s width and its sides is almost the same – making it almost a cube, like Poplar Forest. The staircase and upper floor divide the room vertically. Because of that, rather than splitting images, on two of the eight sides, four panels of approximately square dimensions cover half of the height of the room. The two remaining half-sides are the entrance and exit – the latter with a quarter-side panel above.

Even though two of my images have been reproduced larger (50 feet wide) before in an airport, this time I was stunned by the immersive effect of the wall-to-wall towering panels. The 5×7 transparencies held up well to the enlargements. By default, I have them drum-scanned to a file size of 300MB (about 12,000 pixels in the largest dimension), but for mural reproduction, they are generally rescanned to a 2GB file (approximately 30,000 pixels in the largest dimension). As it climbs up, the staircase partly hides some of the panels. The one at its beginning is visible at its full height. For it, the designers from Thinkwell created a composite out of three photographs made in the same location, the Loggerhead Key of Dry Tortugas National Park.

The choice of images conveyed the geographic extent of the national park system from east to west and north to south (Acadia/Joshua) as well as its diversity of natural environments. It was also a nice mix of iconic locations (the most popular trail in Yosemite, three well-known parks on the Colorado Plateau: Grand Canyon, Bryce, Arches) and lesser-known areas conducive to adventure, like Voyageurs, Glacier Bay, and Dry Tortugas, which are all explored on water.

The US Department of State invited me to Expo 2020 to speak about my work in the national parks. The visit was initially planned for early January, but my heart sank when it was canceled due to the Omicron surge. Fortunately, it eventually took place in mid-February. I did a quick book signing. Given the venue’s extreme distance to the national parks and that any buyer would have to walk around with the 9 lbs book, it was not a given that copies of Treasured Lands at the Rocket Store would sell, so I was pleased to see that even there they were a best-selling book and only a few of them were left to sign. The main goal of the visit was to deliver talks about the national parks and my work in them, and there were also a number of interviews. Below is a photo with Commissioner General Bob Clark in front of the Arches National Park panel.

The #USAPavilion features a series of majestic images by American photographer QT Luong. We are proud to host him as a guest speaker this week. @terragalleria#USAExpo2020 #Expo2020 #Dubai pic.twitter.com/7svBPo32kZ

— USA Expo 2020 (@USAExpo2020) February 15, 2022

The first talk was a non-technical introduction to landscape photography as an event for a group of Youth Ambassadors. Those friendly and enthusiastic college-age men and women are the human faces of the USA pavilion. They serve in different roles that include greeting visitors, guiding them through exhibits, and also assisting official guests like me through the day. I am grateful to all, but particularly to Katrina, Salsabila, Cecilia, and Taty for helping me in various ways to make the most of my short time at Expo 2020.

The second talk took place at the Rocket Garden of the USA Pavilion, right after Andrew O’Shaughnessy’s talk. I discussed the idea of national parks and what makes those in America special before commenting on my photographs in the pavilion with a small print of each as a visual aid. The event continued with a Q&A session moderated by Katrina.

The third talk took place at the Terra Auditorium of the Sustainability Pavilion and was a visual presentation introducing the incredible diversity and beauty of America’s national park system through photographs of each of them. I am thankful to Adel Dekinesh, Nadia Ziyadeh, Maya Nadao-Fall and the rest of the team at the US Consulate General in Dubai for this opportunity to present my work to a global audience, and for all the excellent arrangements during this visit.

I often start my talks by pointing out that I was an unlikely person to have photographed the US national parks. I suppose that I am no longer an unlikely person to turn to for photographs of them. The past photographers seen below happen to be the four mentioned by Dayton Duncan in the foreword to Treasured Lands.

I am grateful to the US Department of State and Thinkwell for selecting my work for the USA Pavilion and displaying it so beautifully in such a high-profile venue. I am so proud that it was deemed worthy of representing the best of what America can offer to the world.