http://www.terragalleria.com/blog/park-anniversaries-celebrated-in-visitor-guides-and-stamps

On the 109th anniversary of the National Park Service (NPS), this article continues my examination of the official NPS visitor guides over the years, focusing this time on how anniversaries have been commemorated in their design. If you haven’t done so, reading the previous installments of this series will provide context.

Part 5 of an on-going series: 1 |

2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | to be continued

Major milestones — whether for a single park or the entire system — have often been occasions for special logos, taglines, or commemorative editions. Yet the way these anniversaries have been acknowledged has varied widely, depending on the era, the park, and the prevailing design standards. From early, locally driven additions to covers, to the tightly controlled visual language of the Unigrid era, these choices reveal not only changing graphic priorities but also how the NPS has chosen to tell its own story – reinforced by United States Postal Service stamps whose messaging echoes the NPS. By tracing these commemorative markings across time, we can see how the visitor guide itself has been used as both a tool for orientation and a vehicle for celebration.

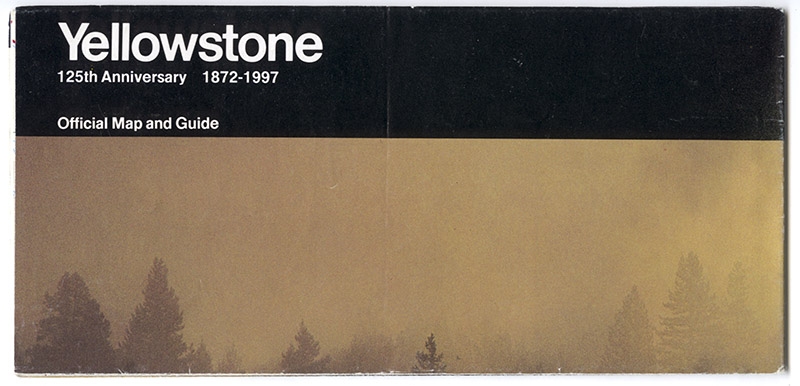

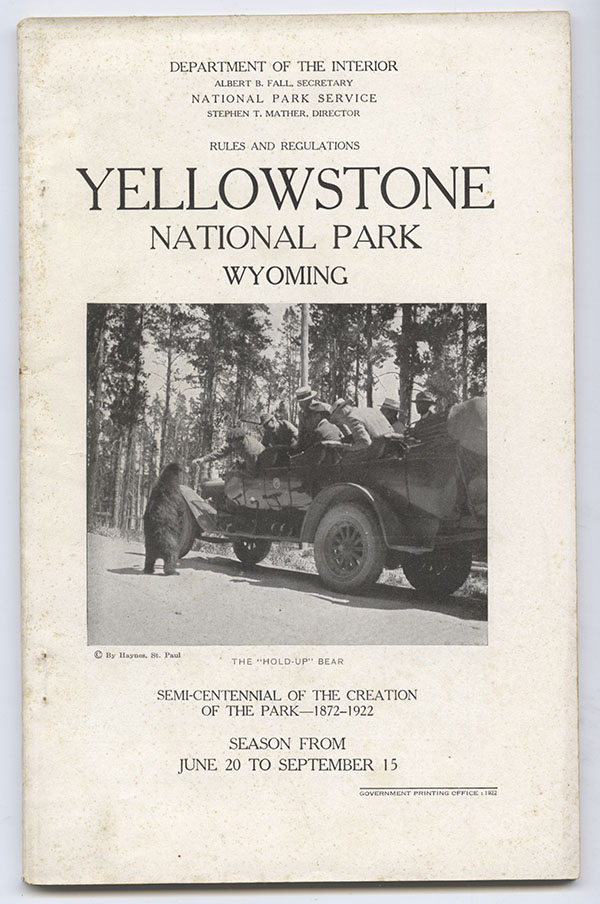

Yellowstone @ 50 (1922)

In 1922, the National Park Service (NPS) was just six years old. Budgets were small, and there was no mature publicity apparatus to turn Yellowstone’s 50th anniversary into a system-wide event. Commemorations took place within the park: a July 14 gathering at the historic Washburn Expedition site, theatrical presentations at Lake Lodge reenacting President Grant signing the park’s founding bill, and some national press coverage. But there was no coordinated national campaign. The visitor guide booklet for that year mentioned the anniversary only in a subtitle, and the occasion was not framed as a “semi-centennial of the national parks”. To the best of my knowledge, it remains the only visitor guide to celebrate a park semi-centennial. It had 112 pages more than any other visitor guide (compared to today’s unigrids!) except for the 1921 Yellowstone guide which had 116.

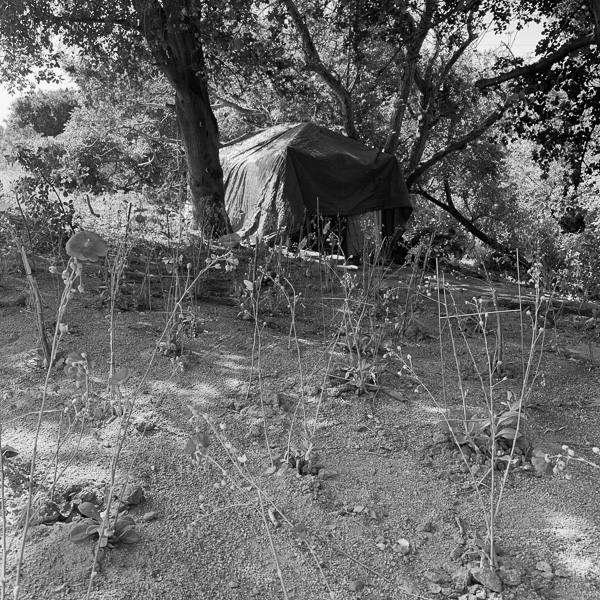

1922 Visitor guide for Yellowstone National Park. This is the favorite item in my collection because of the early date, anniversary, and the historically significant cover photograph (discussion).

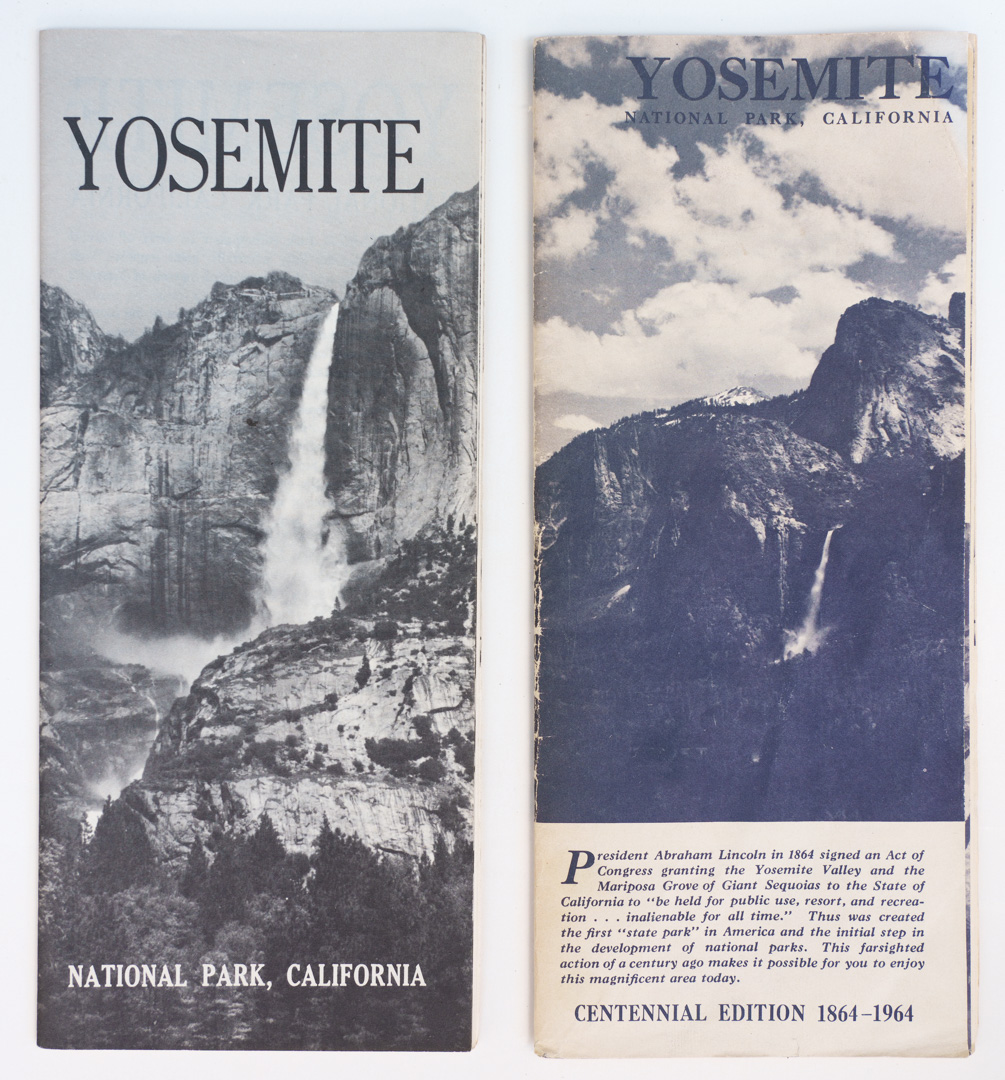

Yosemite @ 100 (1964)

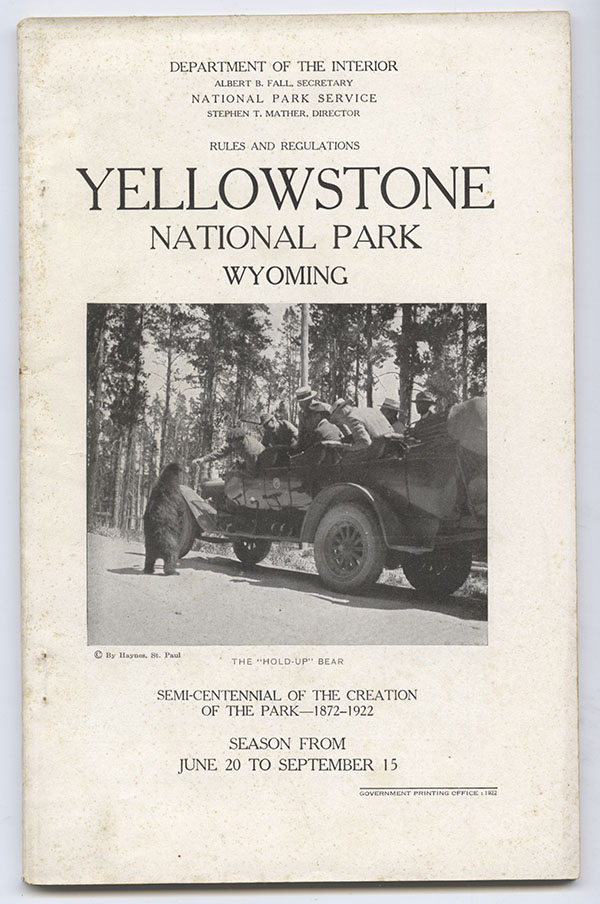

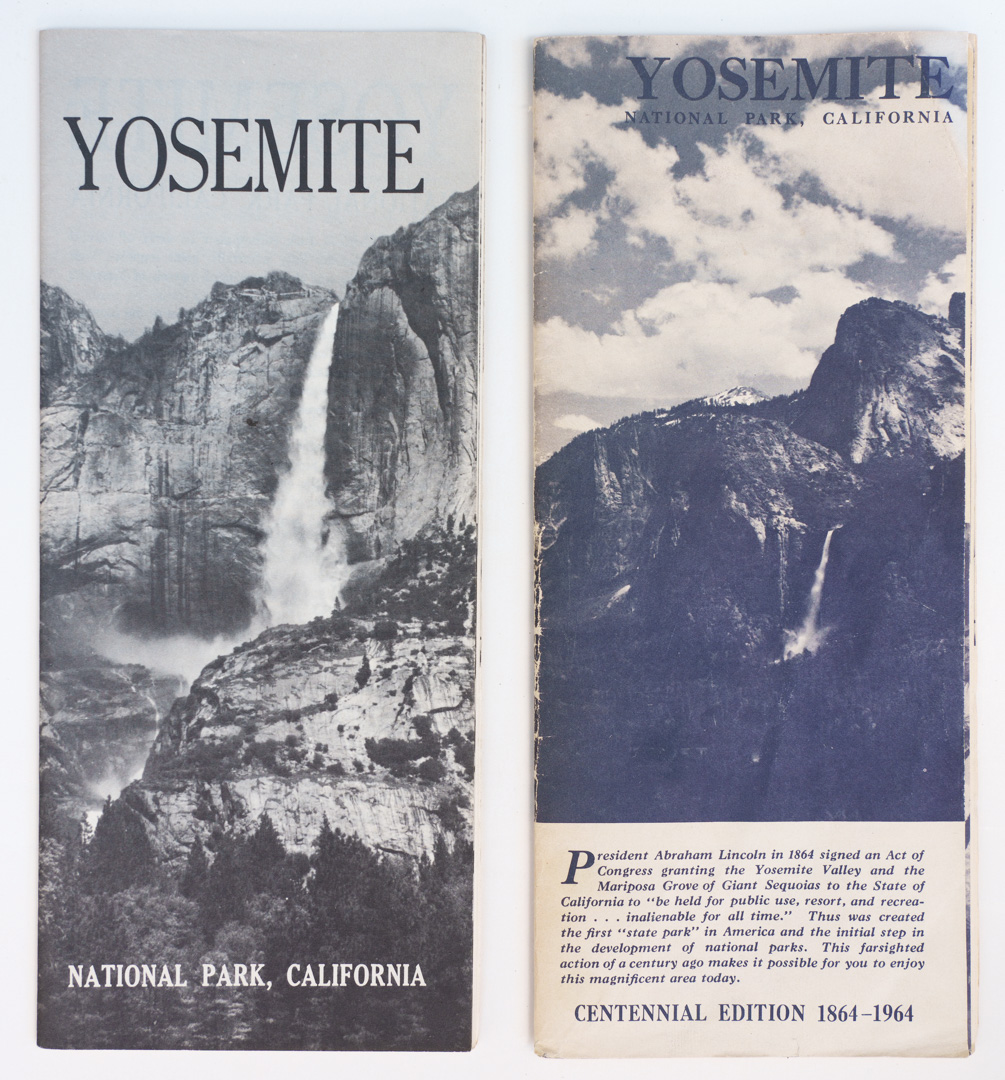

The Yosemite Centennial marked 100 years since the

Yosemite Grant Act, in which Abraham Lincoln set aside Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove for preservation by the State of California — a precedent many historians consider the conceptual forerunner of the national park idea, even though Yosemite National Park wasn’t created until 1890. The celebration remained park-specific, but it drew national attention to the principle that public lands could be permanently protected for public benefit. Coming two years before the NPS’s 50th anniversary and amid Mission 66 improvements, it showcased Yosemite’s modernization and gave the NPS a chance to test strategies later used in broader campaigns. The 1964 visitor guide folder introduced a dramatically revised design to emphasize the occasion. By constrast, in 1990, the centennial of the establishment of Yosemite National Park, the unigrid visitor guide did not mark the occasion.

1963 (left) and 1964 (right) Yosemite National Park visitor guides.

NPS @ 50 (1966)

By 1966, the NPS had grown into a large, unified bureaucracy managing parks nationwide. The 50th anniversary coincided with — and served as the culmination of — Mission 66, a decade-long modernization program explicitly planned to conclude in the anniversary year. The milestone drew system-wide focus, including a US Postal Service stamp and publicity around more than 100 new visitor centers and related facilities. The 50th was as much a celebration of institutional maturity and infrastructure achievement as it was an anniversary. Many brochures from the years leading up to 1966 included a short paragraph about Mission 66 (

see some of them), but the special 50th-anniversary emblem appears on a more limited set and was added by stamping the brochures afterward — I’ve seen it only on a few park brochures. Besides that stamp, there did not appear to be an official 50th anniversary logo. The Parkscape logo,

first used in an exhibit celebrating the NPS’ 50th Anniversary was subsequently adopted as the NPS emblem

as explained in the previous installment.

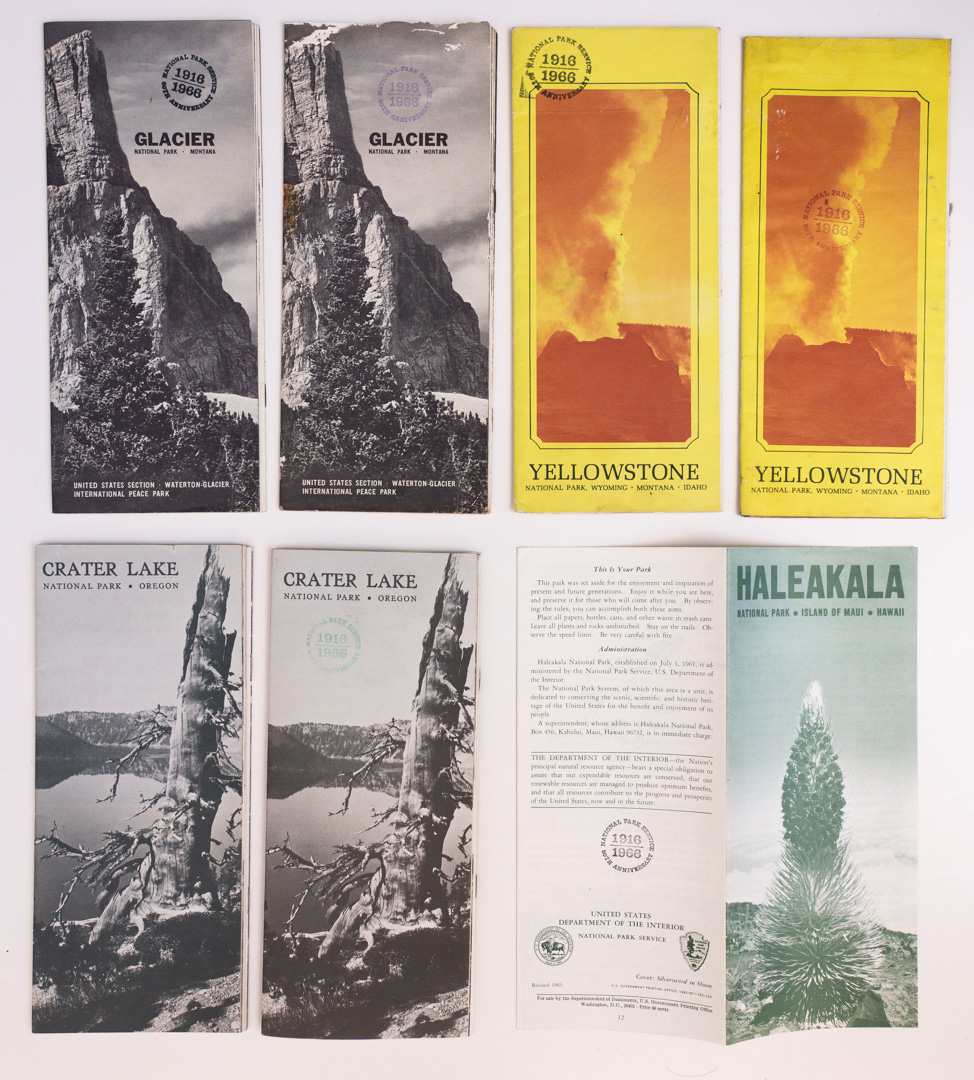

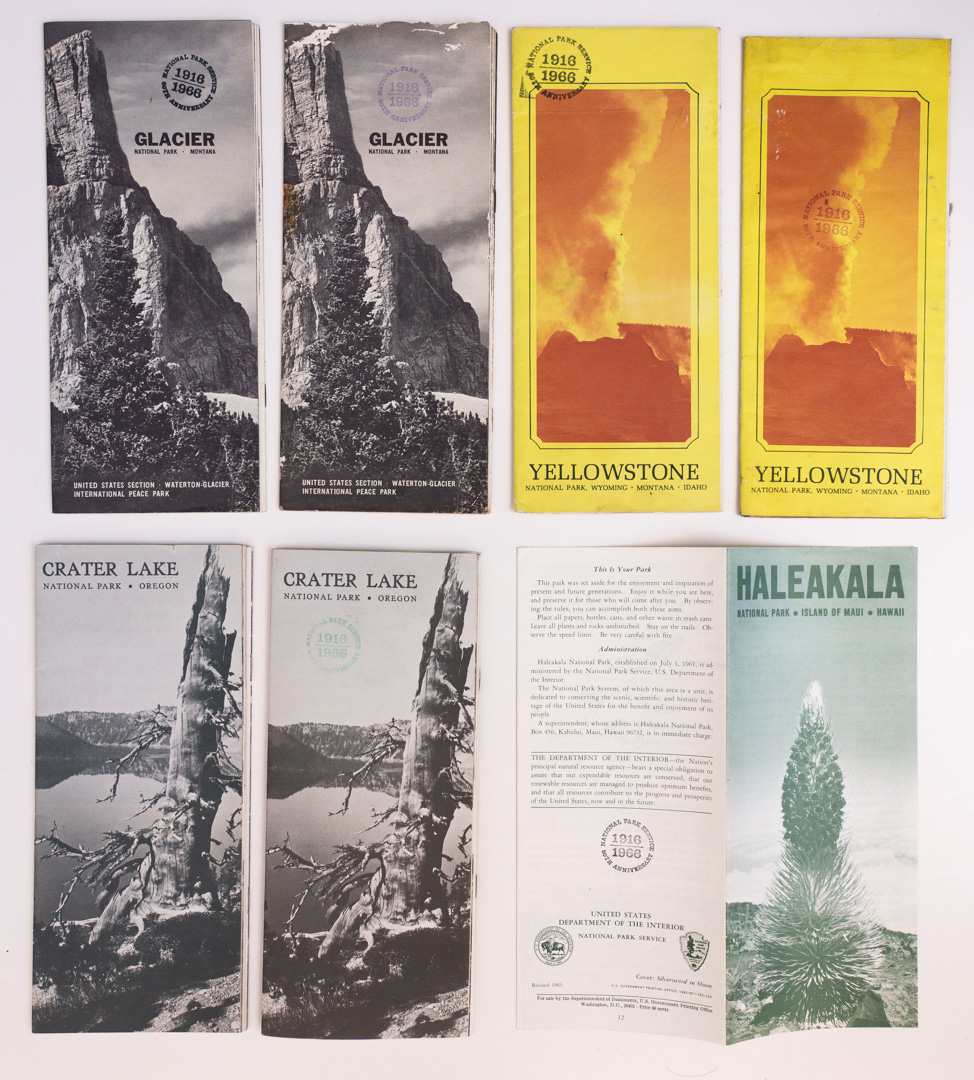

Top: Two copies of 1966 Glacier National Park and Yellowstone National Park Visitor guides with the “1916-1966” stamped differently on the cover. Bottom left: Two copies of 1966 Crater Lake National Park, with and without the stamp. Bottom right: 1966 Haleakalā National Park with “1916-1966” stamped on the back page.

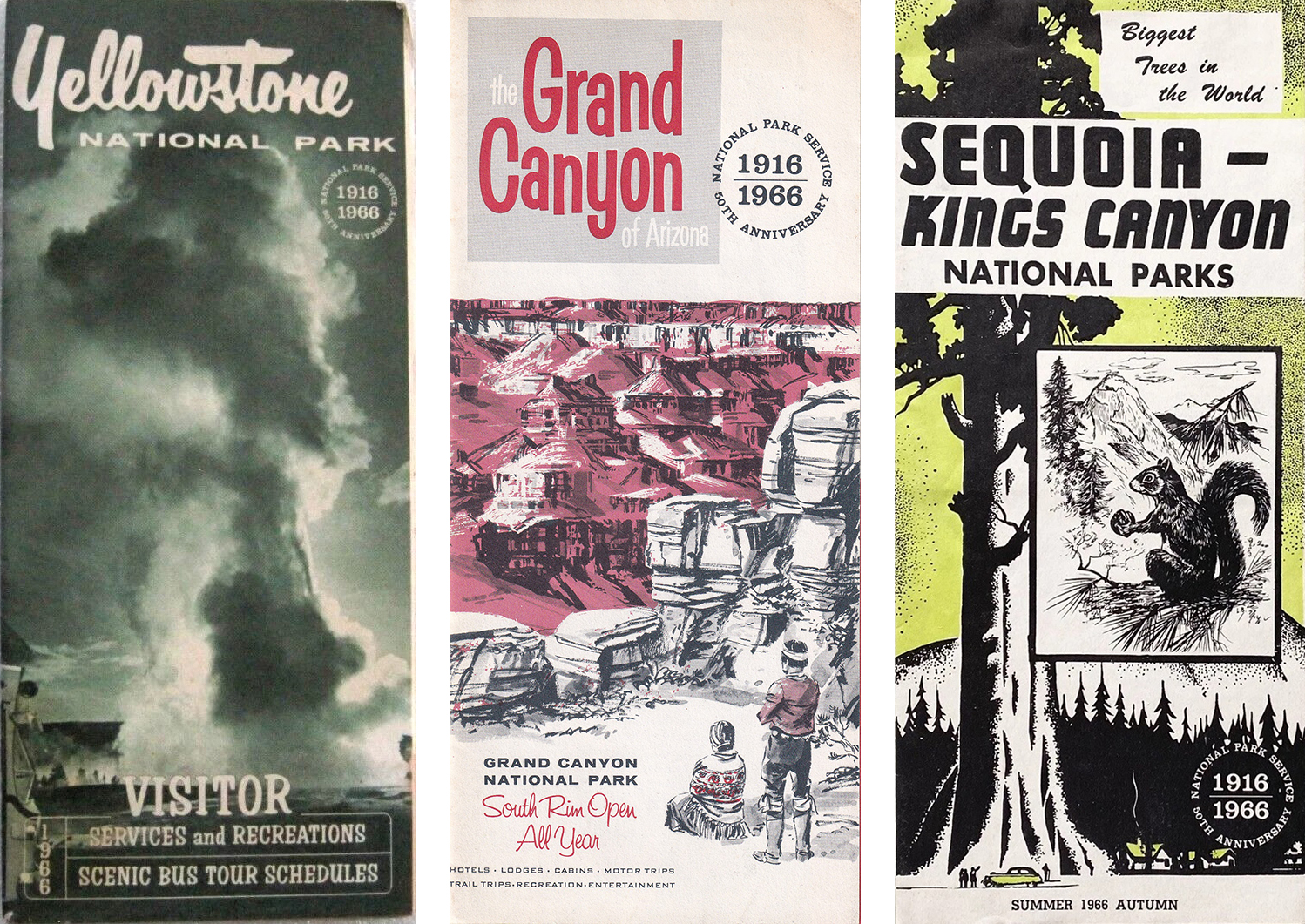

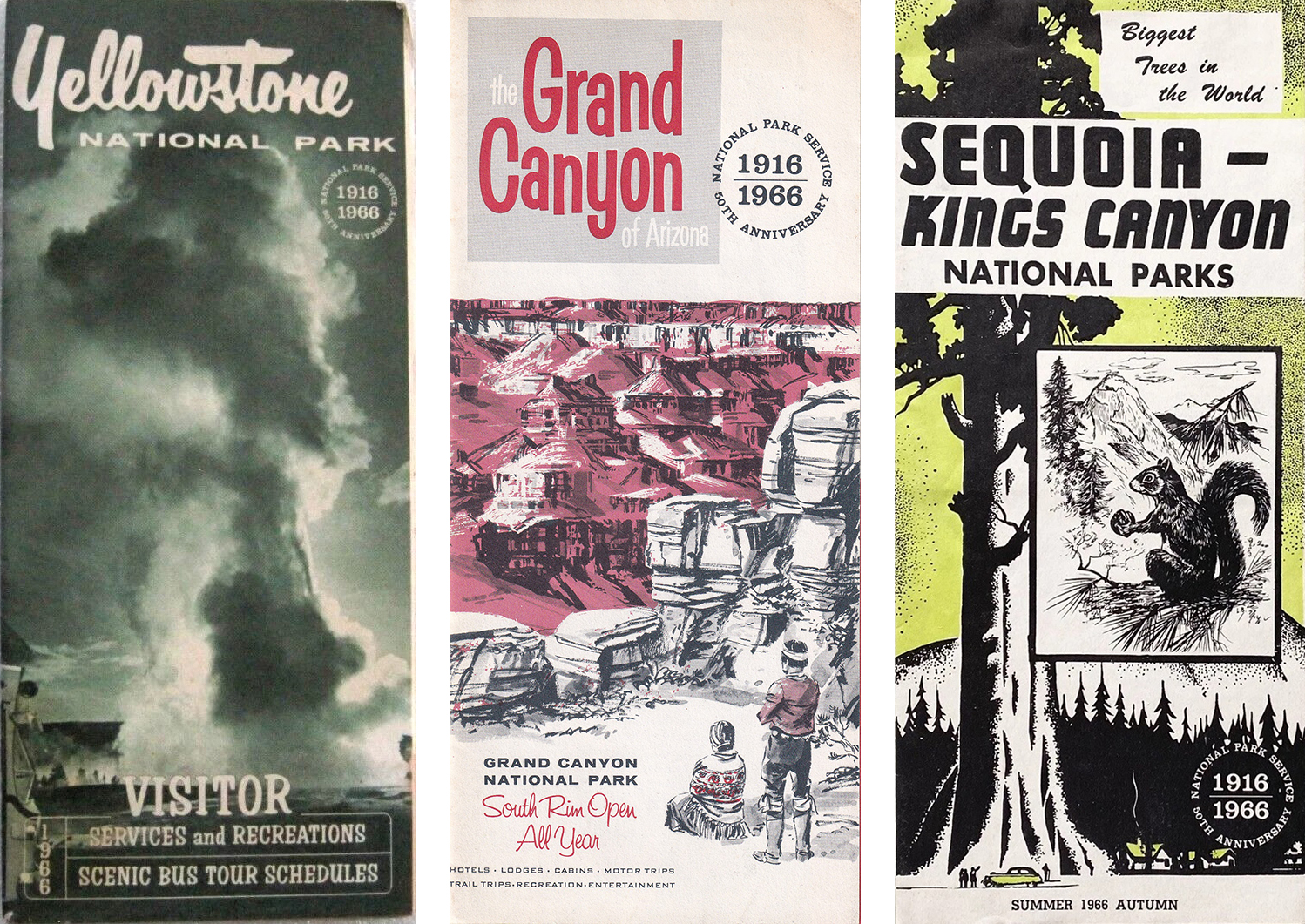

Left: 1966 Yellowstone National Park Visitor services brochure from NPS with “1916-1966” printed on the cover. Unlike the main park visitor guides which are more enduring, those additional brochures included only yearly (or sometimes seasonally) specific information about services provided by the park. They are nowadays issued on newsprint. Right: Grand Canyon and Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks brochures issued by park concessionaires with “1916-1966” printed on the cover, which are also about services. Photos courtesy of Craig Bailey from NPTC.

National Park Service 1916-1966 First Day Cover with the Parkscape logo.

Yellowstone @ 100 (1972)

By 1972, Yellowstone’s creation had been reframed as the birth of the “national parks idea,” a story with global resonance. The NPS treated the centennial as a system-wide commemoration — “100 Years of National Parks”, the first major system-wide commemoration of national parks. The campaign goals were to reinforce the parks ideals, deepen conservation messaging, encourage cooperation, and foster international dialogue. The government also wanted to highlight the American heritage of national parks during a period of environmental awakening (Earth Day had just begun in 1970). The centennial aligned with a push to expand the park system and promote recreation as a patriotic, unifying activity.

Badge with 1972 Centennial logo.

The distinctive logo was a stylized graphic representing Old Faithful geyser. It can be

seen on a badge with the left-aligned words “National Parks Centennial 1872-1972” inside the circle, a combination that I could not locate anywhere in print: at the small size the graphic was commonly printed, the words would not have been legible. Instead, in brochures, the words were printed outside of the logo.

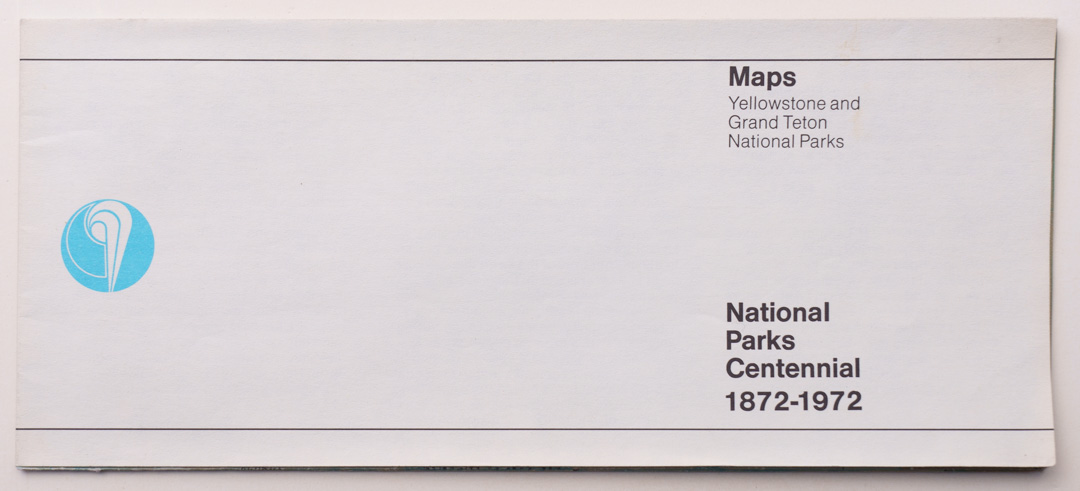

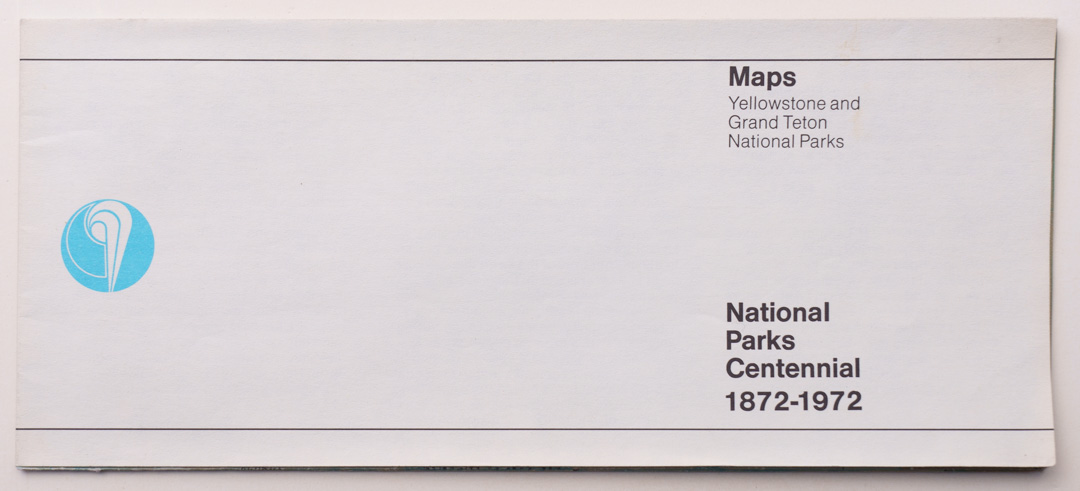

1972 joint map brochure for Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks.

In the years 1972 and 1973, in addition to their respective pocket guides, the two neighboring Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, once considered for inclusion into a single enlarged park, issued a joint larger brochure (4×9″ versus 3 1/4″ x 5 5/8″ for the pocket guides) featuring a map of each park on each side, but no other visitor information – an also taken by Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. The 1972 edition of the map brochure for Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks included the centennial logo and the left-aligned words on the cover. Besides those two parks, the logo and inscription appeared on pocket-guide brochures throughout the system, with the words in a single line.

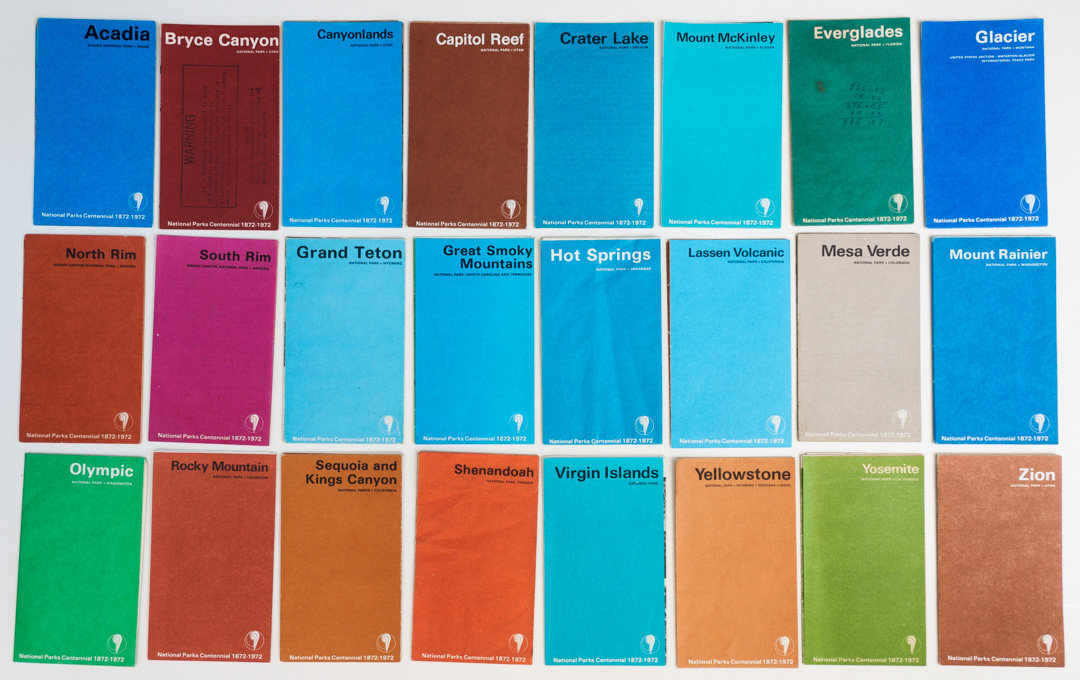

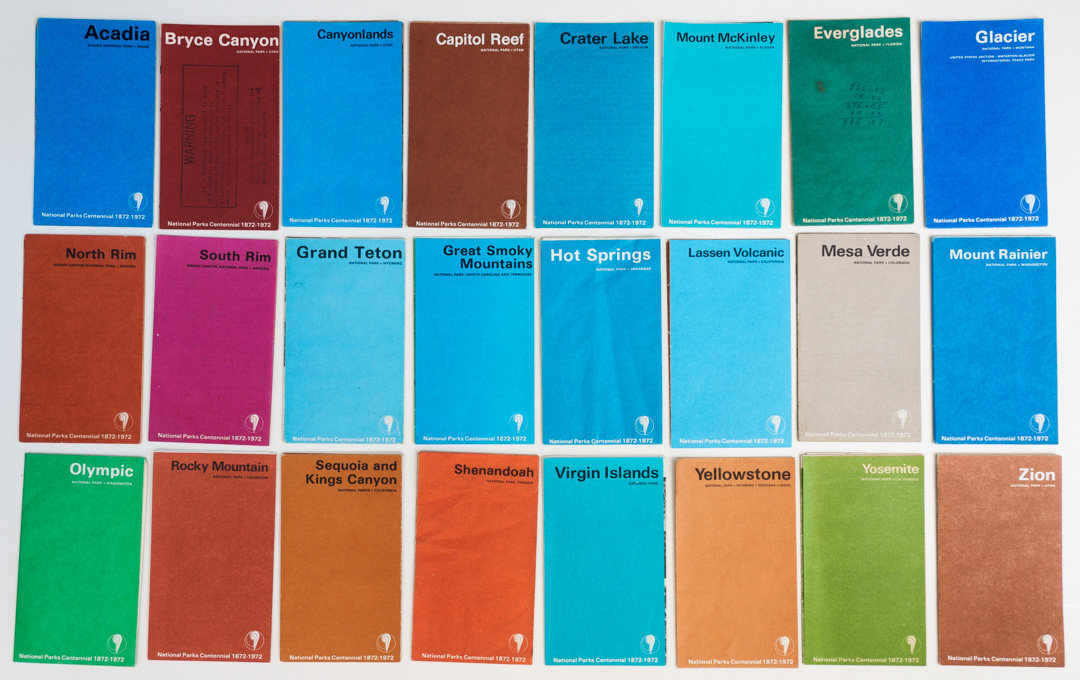

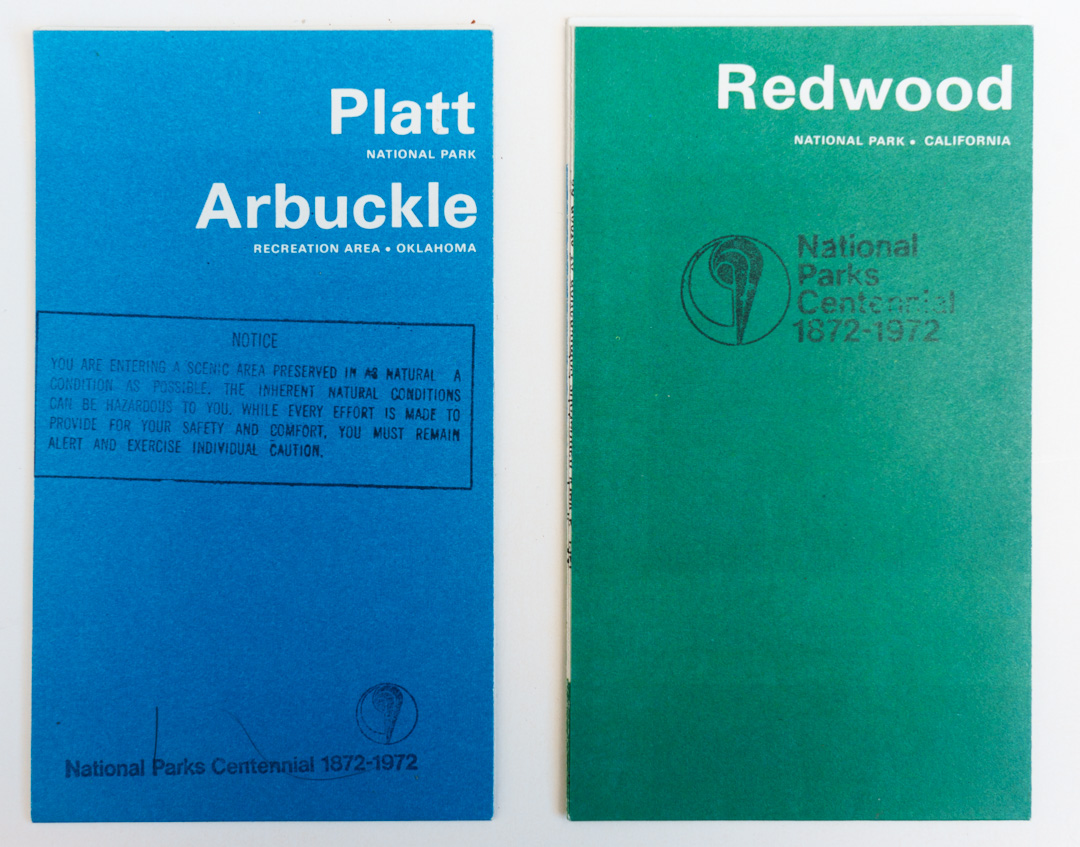

National park pocket guides with the centennial logo and inscription printed.

Of the 39 national parks then in existence, 36 used the pocket-guide format; 28 featured the centennial logo and text prominently at the bottom of the plain panel.

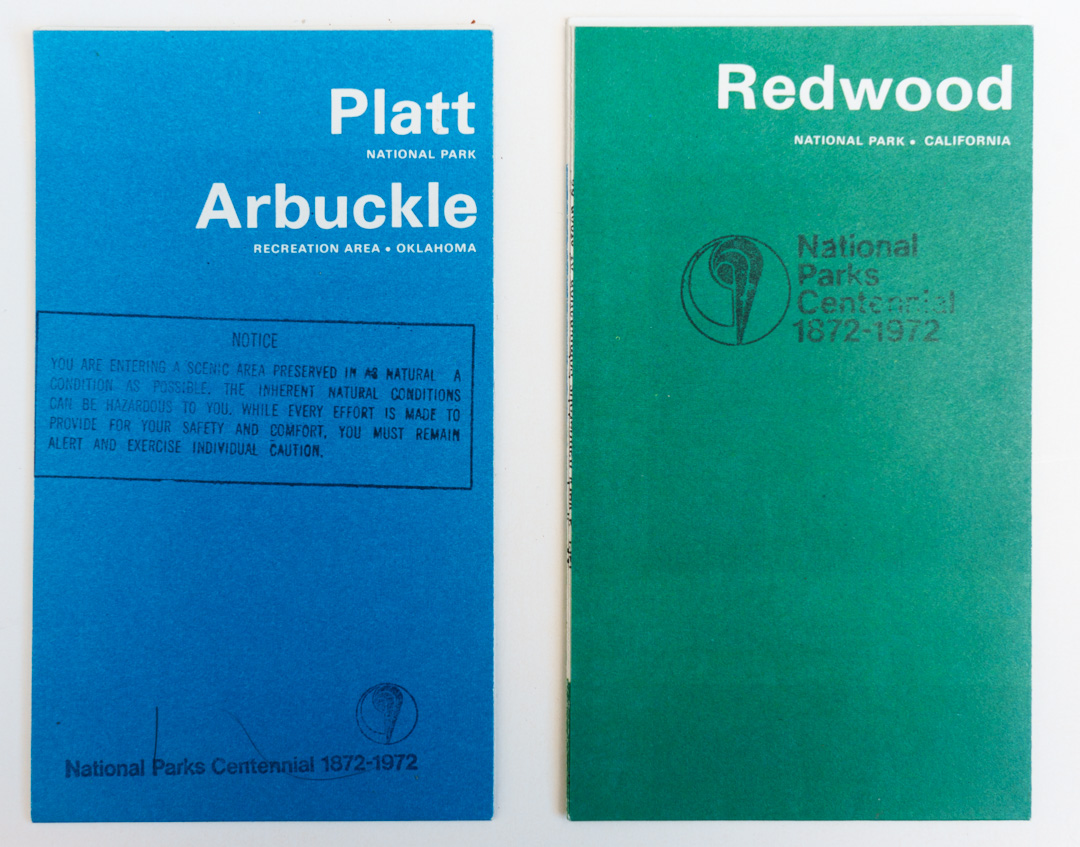

As far as I know, two park brochures were printed without those markings, but had them added through a stamp. By the way, if you haven’t heard of Platt National Park, it was the black sheep of the national parks. In 1976, the NPS eventually managed to merge it with Arbuckle Recreation Area into the more appropriately named Chickasaw National Recreation Area.

Two national park pocket guides with the centennial logo and inscription added afterward by stamp – with words on a single line or four left-aligned lines

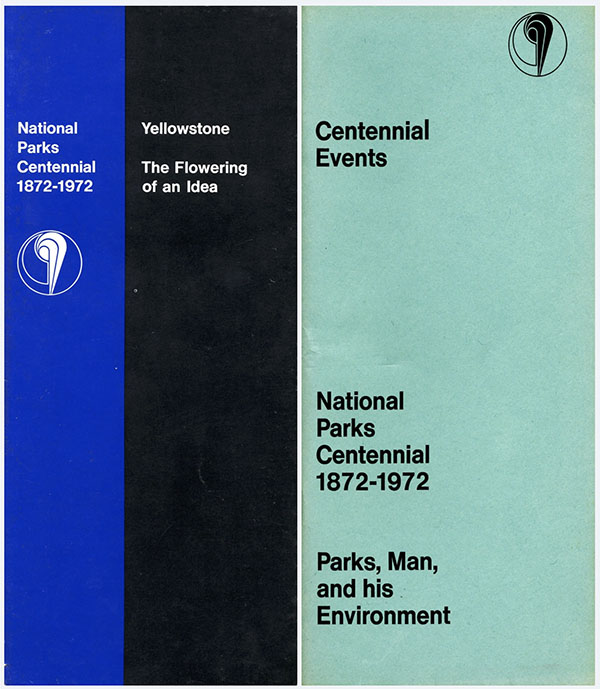

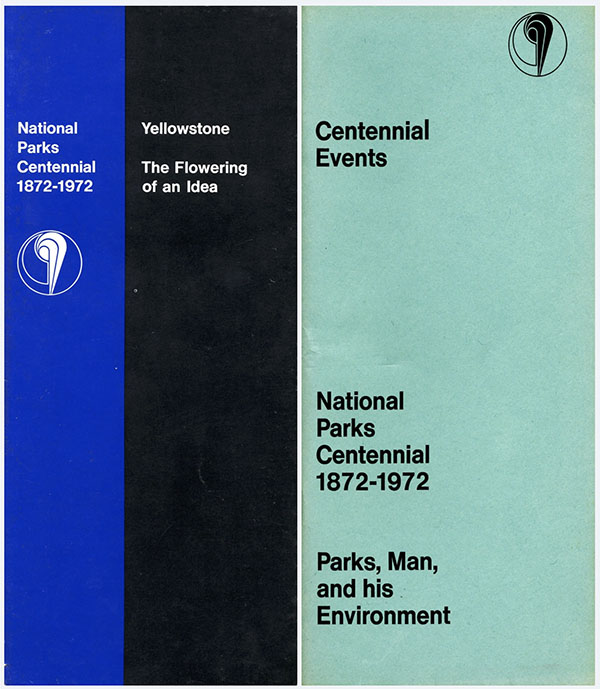

Only seven lacked it entirely. Three of those seven — Hawai‘i Volcanoes, Haleakalā, and the newly redesignated Arches — used non-pocket-guide 4×9″ formats whose photo-illustrated covers were not conducive to the mark; the others (Isle Royale, Big Bend, Carlsbad Caverns, Mammoth Cave, Wind Cave) used pocket guides but, for reasons unclear, did not receive the markings. The centennial logo and tagline was also similarly featured in the pocket guides for other park units across the entire system. Besides the visitor guides, two special 4×9″ brochures were issued. Yellowstone The Flowering of an Idea focusses on the history of establishing Yellowstone National Park in 1872. Centennial Events, with its 116 pages, reflects the magnitude of the celebration, listing events state by state, as well as other memorabilia and publications, including the USPS stamp set.

Two special NPS brochures issued for the centennial. Photos and information courtesy of Craig Bailey from NPTC.

Unlike the 1966 commemoration that consisted of a single stamp, the USPS released a series of four stamps plus a quartet, each dedicated to a different park site: Yellowstone and Denali National Parks, and three other national park units: Cape Hatteras National Seashore (the first unit with such a designation), City of Refuge National Historical Park (standing for all 170 historic sites; now Pu’uhonua o Honaunau National Historical Park), and the oddball Wolf Trap Farm Park for the Performing Arts (a new dimension in the NPS, centered around an outdoor amphitheater; now Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts). This approach mirrored the NPS strategy that year: the Yellowstone centennial was not just a local milestone but a system-wide moment, emphasizing the breadth of the national park idea.

1972 National Parks Centennial First Day Covers. The phrase ‘Parks, Man and His Environment’ reframed Yellowstone’s anniversary as a forward-looking charge: parks were no longer only about scenic preservation, but about the intertwined future of people and nature. Text in the back of the envelopes says of Yellowstone:

As the first national park it is symbolic of the entire national park movement which has resulted in the creation of national parks in more than 100 nations

In the National Parks Centennial the nation celebrates the 100th anniversary of a uniquely American idea, which has taken root around the world to the lasting benefit of mankind. Now in an era increasingly concerned with the thoughtless squandering of our natural birthright, National Parks can help us to renew our precious contacts with the natural world that gives and sustains life. One hundred years ago a group of Americans worked hard to assure that this nation would preserve its heritage of natural beauty and wonder. The National Parks Centennial seeks both to honor and to perpetuate the results of their vision and courage.

Mount Rainier @ 100 (1999), Rocky Mountain @ 100 (2015), Hawai‘i Volcanoes @ 100 (2016), Grand Canyon @ 100 (2019)

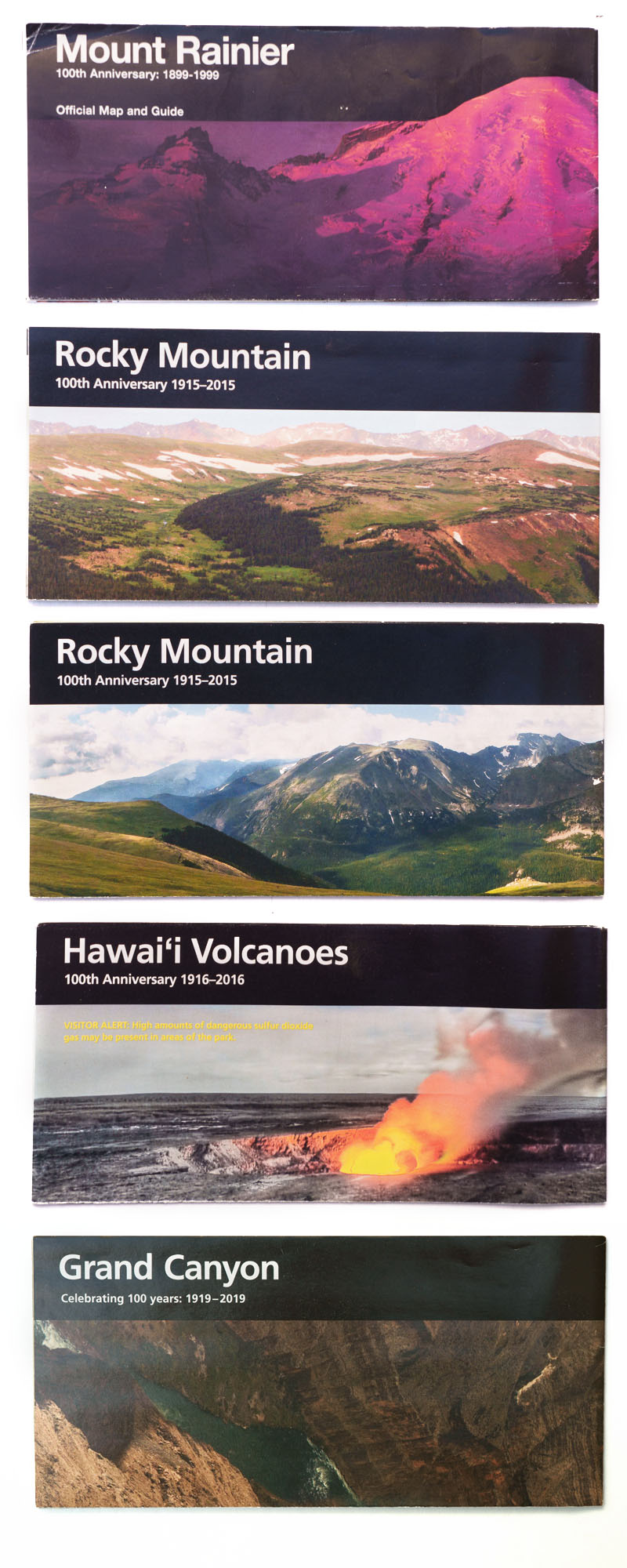

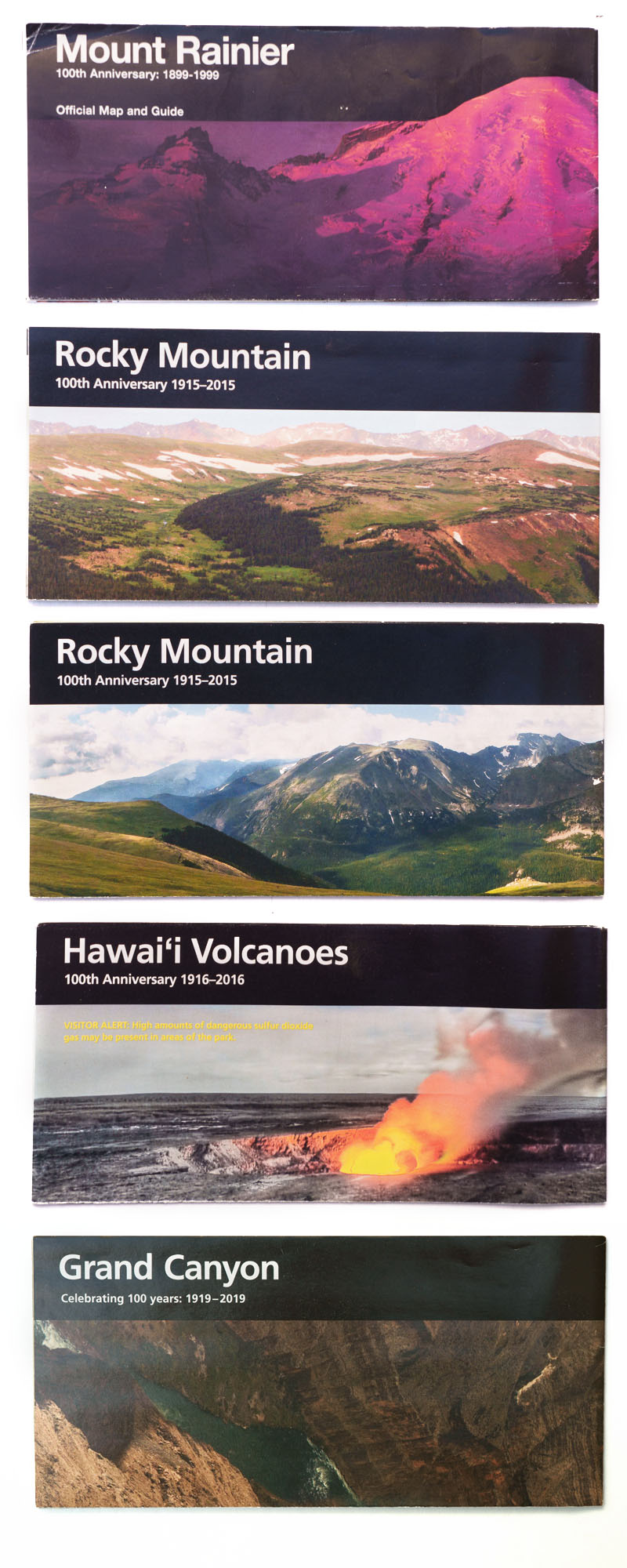

Mount Rainier’s centennial in 1999 marked 100 years since its establishment as the first national park in the Pacific Northwest. While not as significant as Yellowstone’s anniversary, it reflected a growing trend of treating individual park milestones as branding opportunities. In Rainier’s case, the NPS allowed a small centennial tagline on its Unigrid brochure — consistent with standards that generally avoid adding agency or partner logos to maintain the design uniformity sustained since Massimo Vignelli’s Unigrid system was adopted in 1977. Like several other parks (

see examples), Rocky Mountain NP had a widely used official centennial logo in 2015, but it did not appear on its Unigrid; the same was true for Hawai‘i Volcanoes in 2016 and Grand Canyon in 2019. Other national parks celebrated their centennial but did not feature a centennial tagline on their unigrids. Unlike visitor guides from the early days of the NPS that changed each year, the unigrid designs spanned multiple years. Whether a park added a centennial tagline to its Unigrid typically depended on local choice, reprint timing, and budget.

Unigrid brochures with a Centennial tagline (Rocky Mountain National Park issued one for the year 2014 and another for the year 2015).

NPS @ 100 (2016)

By 2016, the NPS had become a national cultural brand managing more than 400 units. The centennial campaign was a fully professional, multi-platform effort aimed at engaging the next generation of visitors and stewards. Its flagship initiative,

Find Your Park, sought to broaden inclusion through media partnerships, special events, and targeted outreach. More so than in 1972, an extensive range of private entities released commemorative products, showcasing their enthusiasm for the national parks and the NPS. Wanting to add my modest part to the celebration, I timed the publication of

Treasured Lands for 2016, as The New York Times noted:

this year the centennial of the National Park Service has been the occasion

of exhibits, documentaries, presidential proclamations and many books. The most

glorious of these is TREASURED LANDS

2016 Centennial logo.

The centennial logo’s main element was the number 2016, where “0” was replaced with a light-green arrowhead outline whose full version was the NPS emblem, accompanied by matching green lettering for the word “centennial”. It was flown in space in celebration of the National Park Service Centennial. The arrowhead outline was also part of National Park Foundation and National Park Service logos, the former becoming the only partner logo featured on Unigrid visitor guides.

Dual National Park Service and National Park Foundation logos

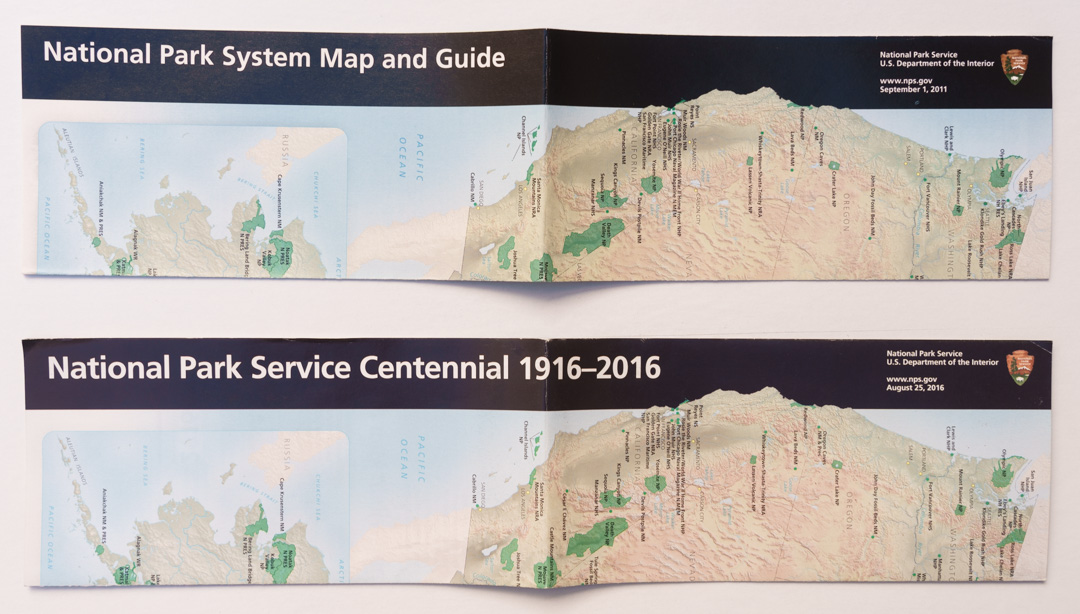

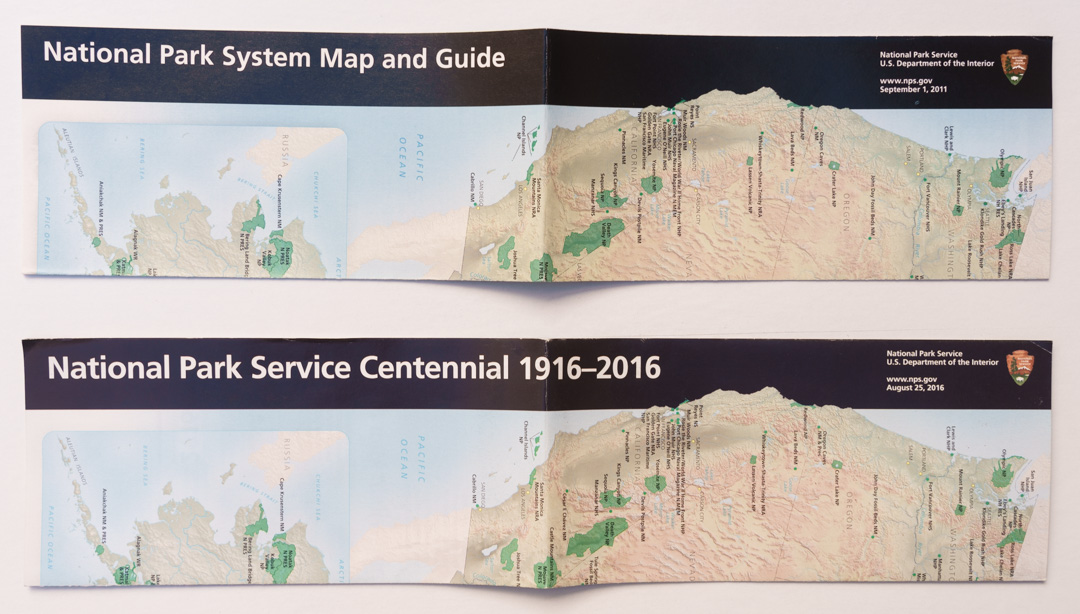

While rather bland, the three new designs were meant to provide a fresh new look as the NPS tried to connect with new audiences. Their simplicity made them versatile, as they could stay legible while used small in various media. However, one medium was the centennial logo did not appear were the individual park Unigrid brochures. The only enduring document where I could find it is the system-wide map and guide. Although the logo is included, it would have been easy to miss, as it did not appear on the front page, but rather on the back page, in a discreet position. That’s nowhere near the level of prominence the 1972 geyser logo had on most pocket guides, where it often sat bold at the bottom of the cover.

Top: 2011 National Park System Map cover, unlike individual unit unigrids, the date of issue is printed on the cover. Middle: 2016 National Park System Map cover, date of issue is the NPS centennial day. Bottom: Verso of the 2016 National Park System map, note the Centennial logo on the bottom right corner

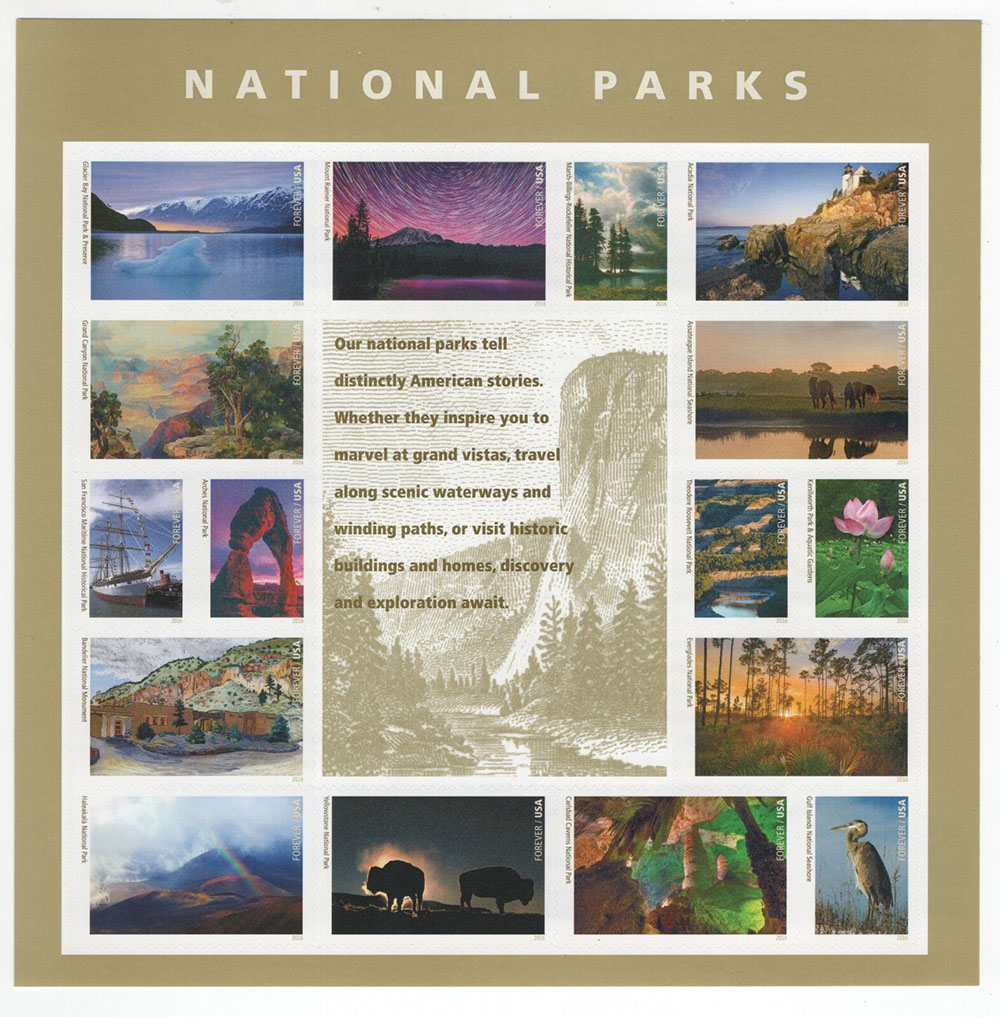

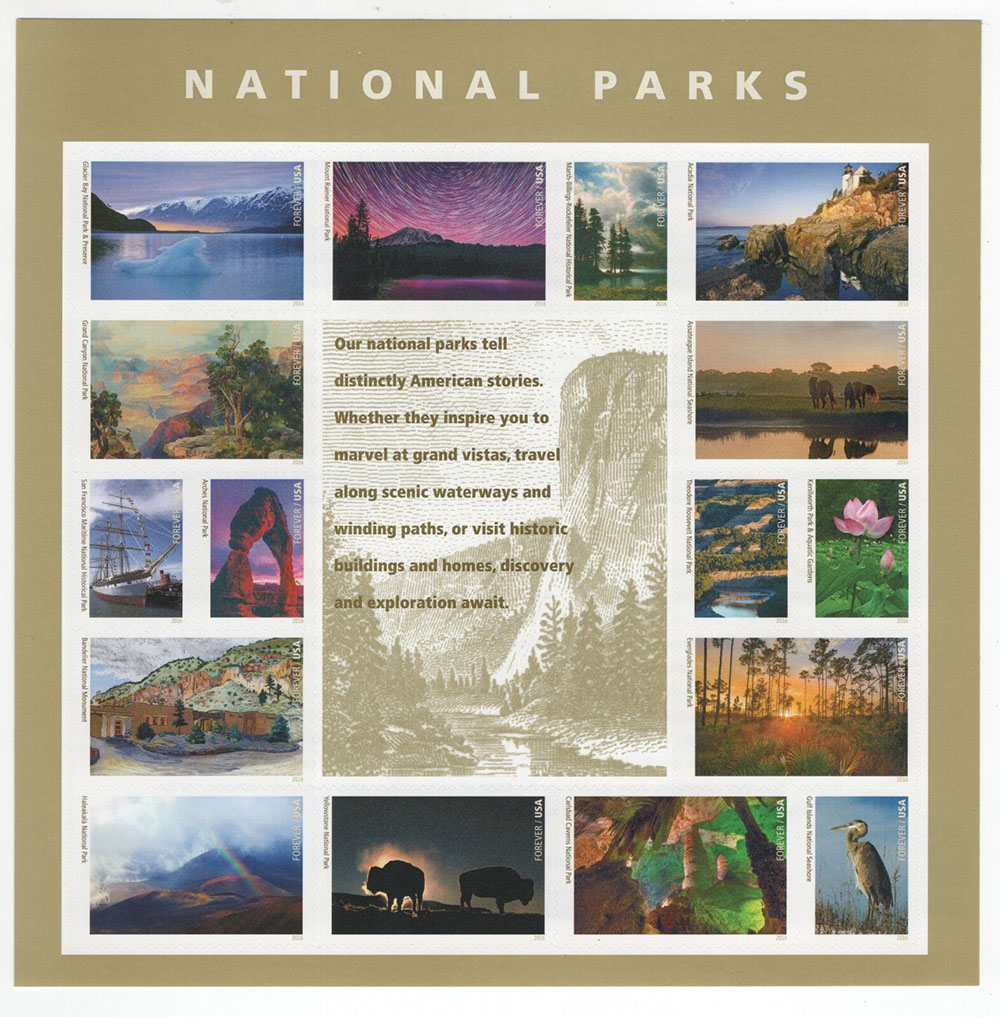

The USPS issued 16 stamps: 10 national parks and 6 other national park units. This number was double from 1972, however, none of them mentioned anything about the centennial. Even the pane featured just the title ““National Parks”; neither the centennial logo nor even the words “Centennial” or “1916–2016” appear anywhere. So while 1966 and 1972 stamps functioned as explicit commemoratives, the 2016 issue was positioned more as a celebration of parks in general rather than a formal centennial mark. It was consistent with the NPS’s broader approach that year, where the centennial logo wasn’t used much on Unigrids.

Instead, it was featured in posters, banners, rack cards, and especially in digital media — reflecting a marketing-driven era, where the centennial was celebrated through outreach and engagement rather than through enduring, printed symbols.

USPS 2016 national parks stamp panel.

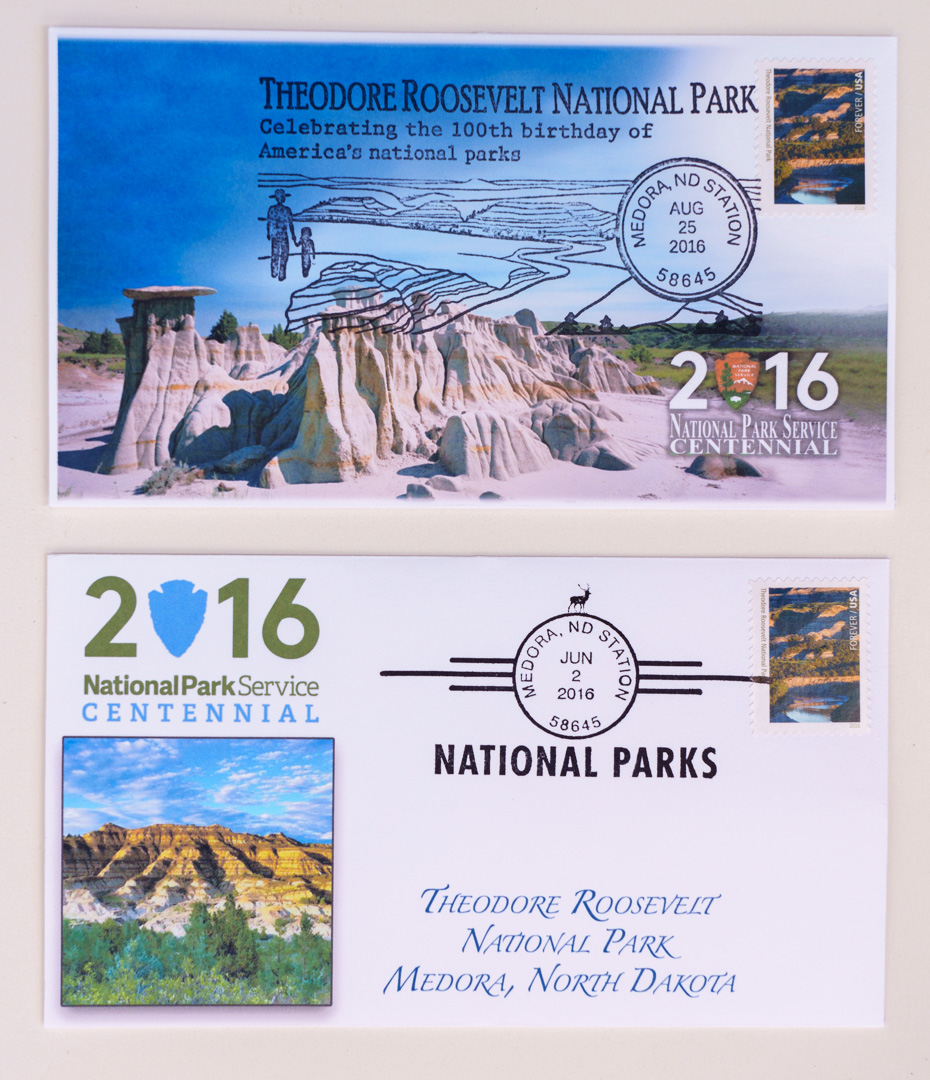

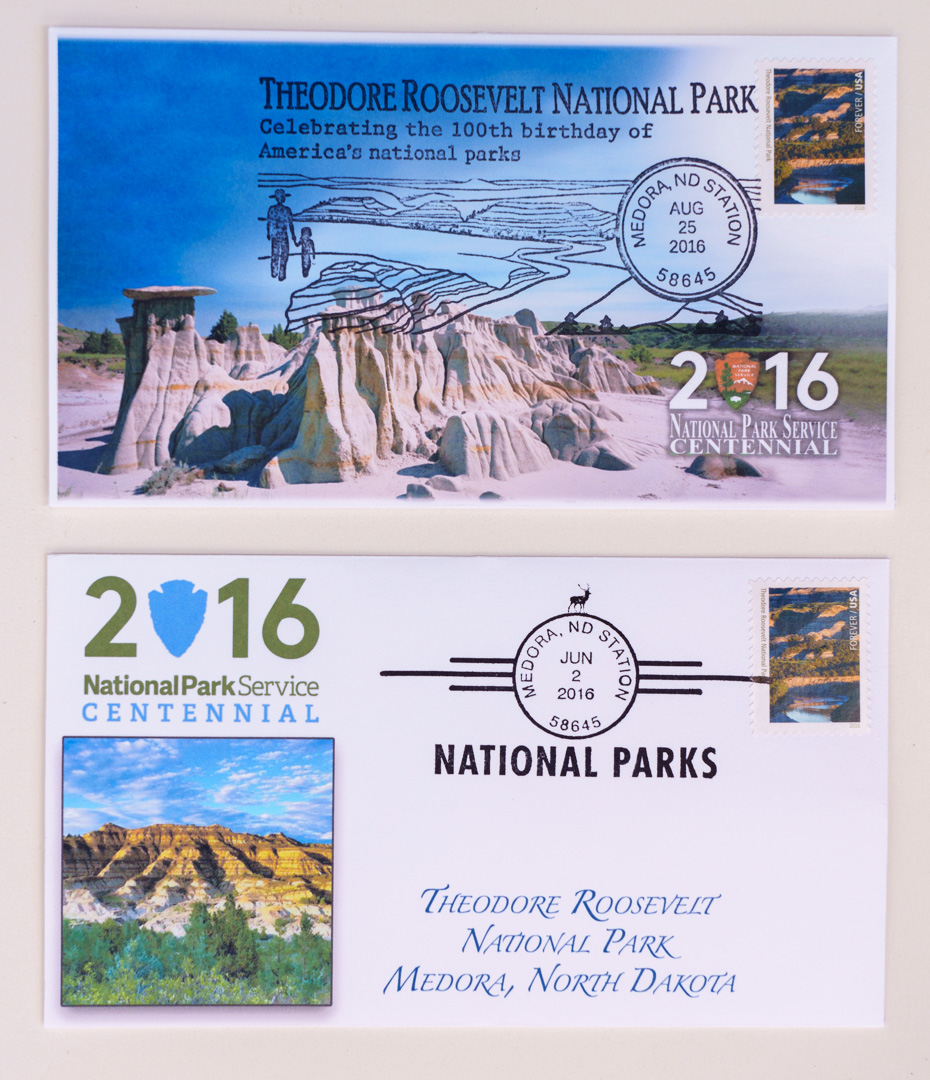

2016 Theodore Roosevelt National Park First Day Covers

featuring QT Luong’s photograph. Note the deviations from the official centennial logo (which features a light green empty arrowhead). While stamps are issued by the USPS, those envelopes were not official.

For some park visitors, the word “stamp” has a different meaning. In National Park Service visitor centers, you’ll find cancellation stamps available for free use at an information desk or stamp station. These are rubber ink stamps (similar to passport stamps) designed for the Passport to Your National Parks program, but anyone can use them in notebooks, guidebooks, or other printed materials – I like to stamp my unigrids.

The Passport to Your National Parks® program, launched in 1986 by Eastern National (a nonprofit partner of the NPS; now America’s National Parks), is a popular collectible activity that encourages exploration of the entire park system. Visitors can purchase a small “passport book,” divided into regions of the country, and then collect cancellation stamps at each park they visit. Many travelers treat it like a travel log, filling its pages with dated impressions and sometimes supplementing them with stickers or notes.

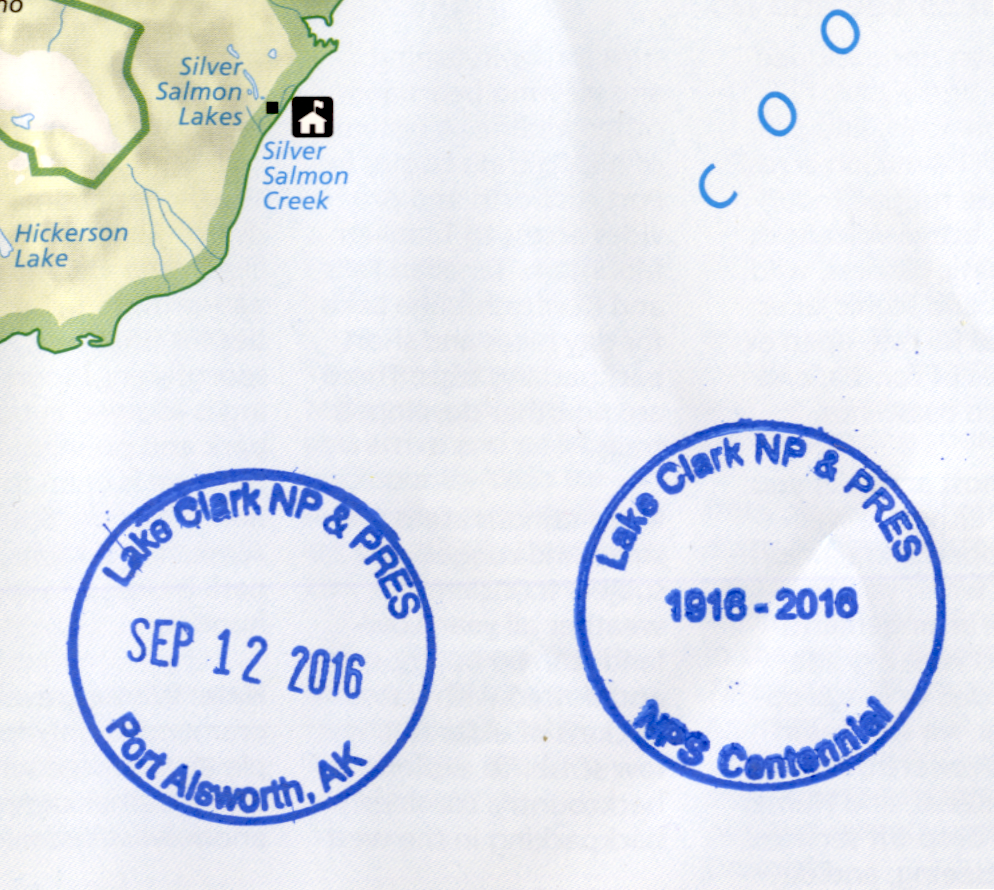

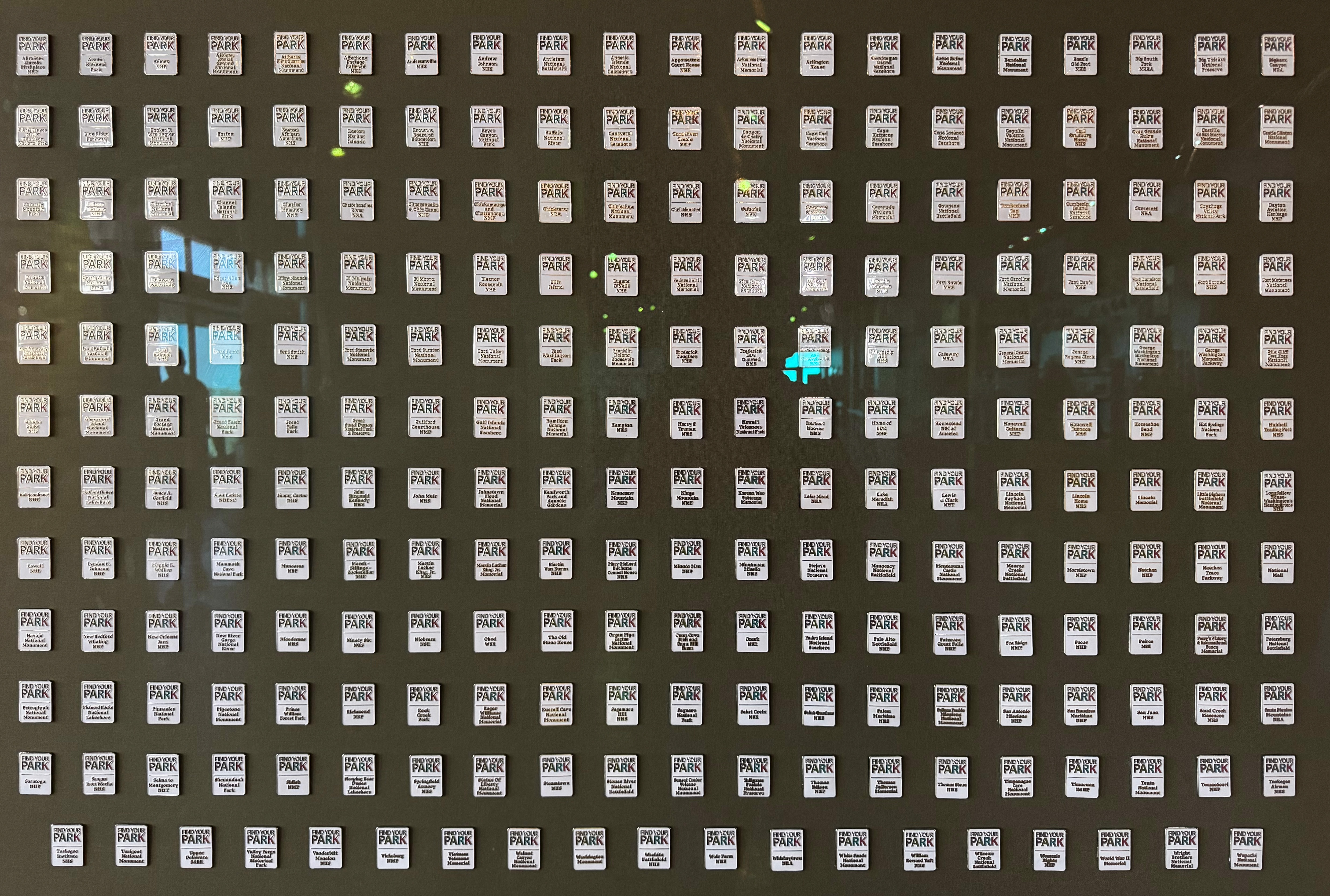

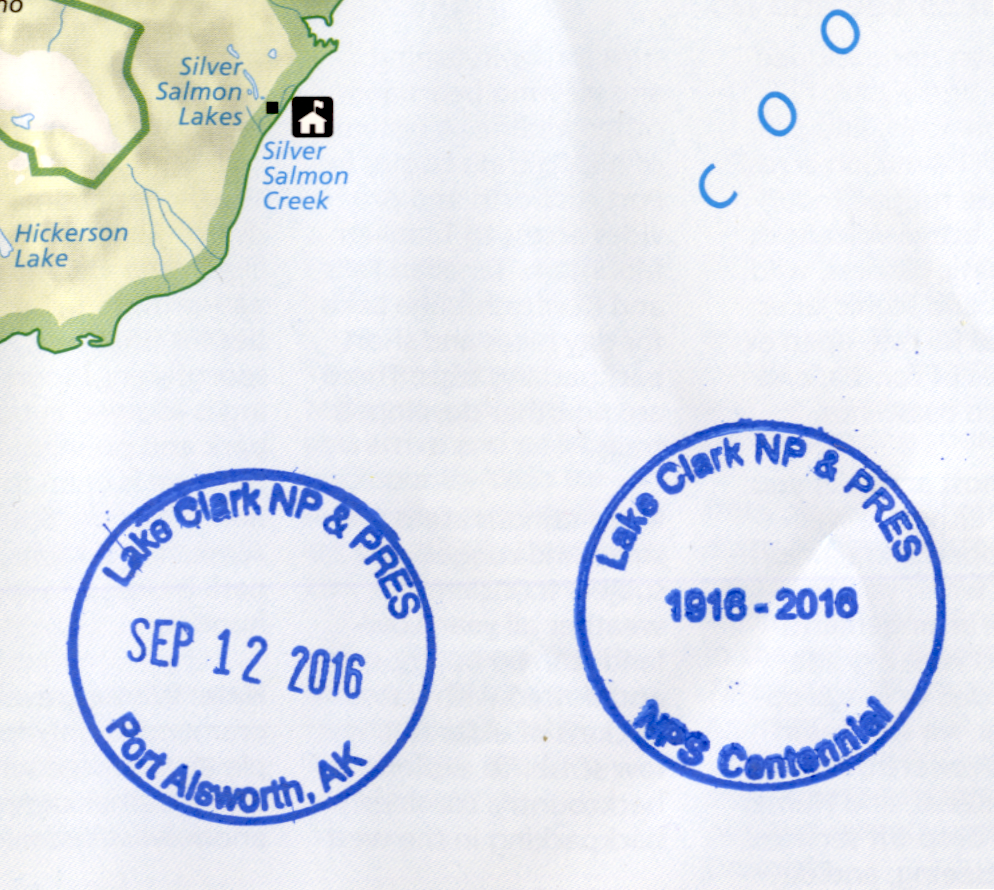

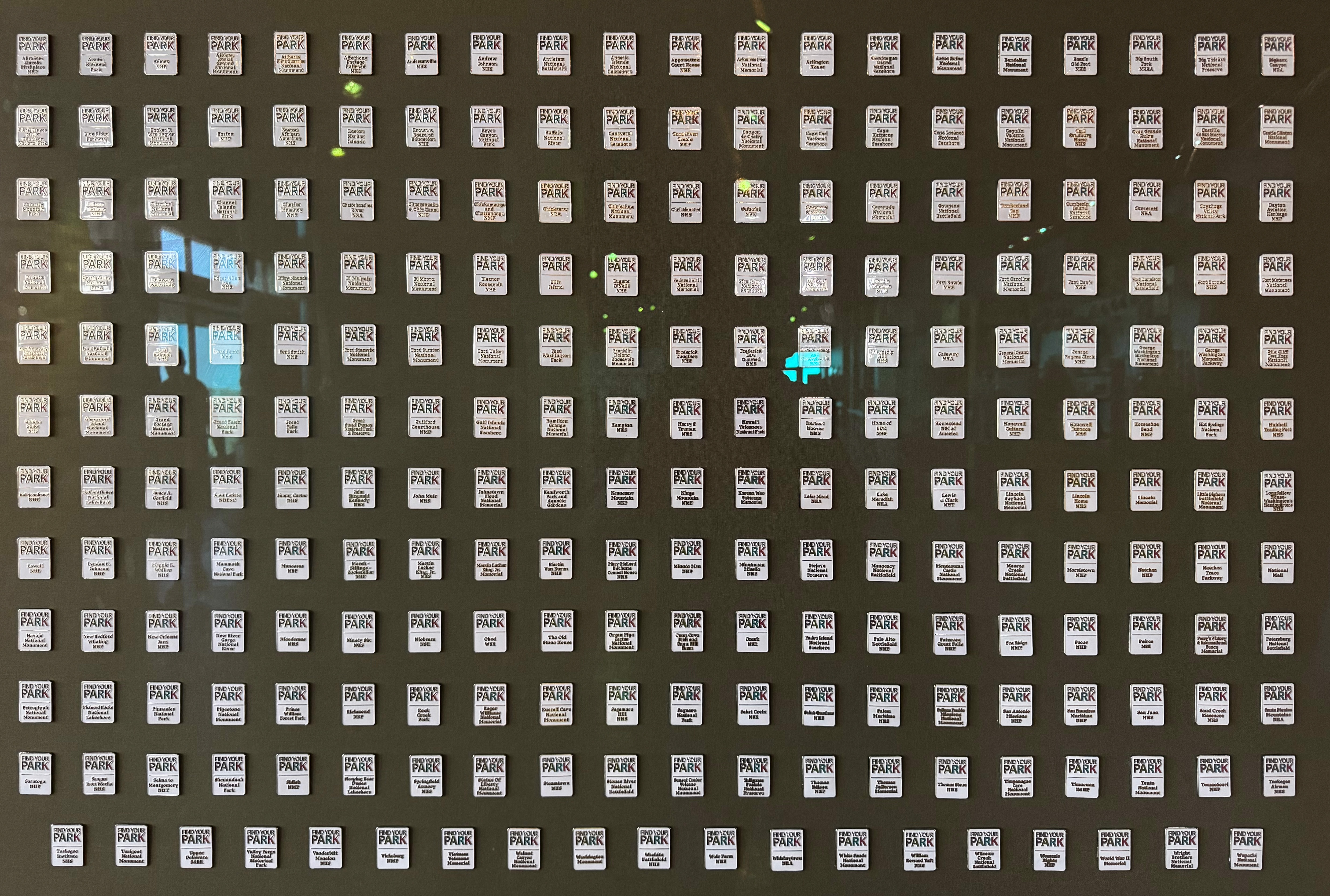

Each cancellation stamp is site-specific: it shows the park’s name, location of the stamp (large parks have more than one visitor center each with own stamp), and date of visit in a circular design. These do not have anything to do with mailing. They are purely commemorative, meant to provide a tangible record of your visit. The National Parks Travelers Club (NPTC) is a group with a considerable collective knowledge about about all aspects of visiting various national park units. Many members are so dedicated to collecting those stamps that the club URL is parkstamps.org. Many park units offer special stamps to commemorate their anniversaries. During the year 2016, all the park units offered a special centennial stamp where the date of the visit was replaced by “1916-2016” and the location of the stamp replaced by “NPS Centennial”. NPTC member David Kroese managed to personally collect 432 of them during an epic trip chronicled in his book The Centennial. Those commemorative stamps supplement rather than replace the regular stamps, marking the milestone in small cultural artifacts that visitors carry home. Other souvenirs included rectangular lapel pins featuring the Centennial and Find Your Park logos on top and the name of the issuing park unit. Kroese visited all the 248 park stores carrying those in 2015-2016, and framed a complete set of them. The display was circulated in many park units, and I happened to see it at Carslbad Caverns National Park in May 2025.

Map detail with regular and 2016 NPS Centennial cancelation stamps for Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Read an

account of the brief visit during which I collected them.

Complete collection of 248 (each) Centennial and Find Your Park lapel pins assembled by David Kroese. (Click to enlarge)

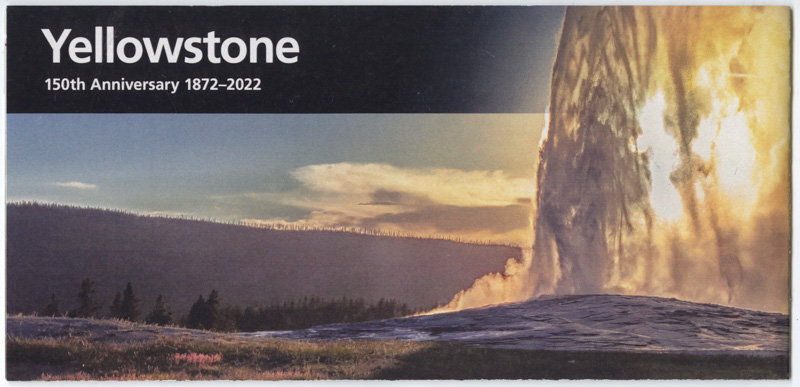

Yellowstone @ 150 (2022)

While the 100th anniversary of Yellowstone National Park was positioned as a proxy for all national parks, leading to national celebrations, its 150th anniversary was treated as a regional event. The context was also different: the 150th took place in the wake of the 2016 NPS Centennial, which had already absorbed national attention, and the U.S. was still in a period of pandemic recovery. The event was branded as “Yellowstone 150”, not tied to the NPS as a whole. Instead, emphasis was on tribal sovereignty, inclusion, and ecological stewardship of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, reflecting contemporary values rather than mass tourism. The NPS marked it like some of the other individual park 100th anniversaries (and Yellowstone 125th anniversary) issuing again just a commemorative unigrid with a tagline – bringing this article to a full circle.

1997 and 2022 Yellowstone National Park unigrid brochures.

These anniversary emblems remind us that national parks are as much cultural constructs as natural landscapes, a perspective that increasingly guides some of my photographic work — and one that underscores the inseparability of people and nature.

PS: I am still trying to complete my collection and I have numerous duplicates, so if you’d be interested in donating, trading, selling, or buying vintage brochures for any NPS units that are currently national parks, please let me know.

Part 5 of an on-going series: 1 |

2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | to be continued

.