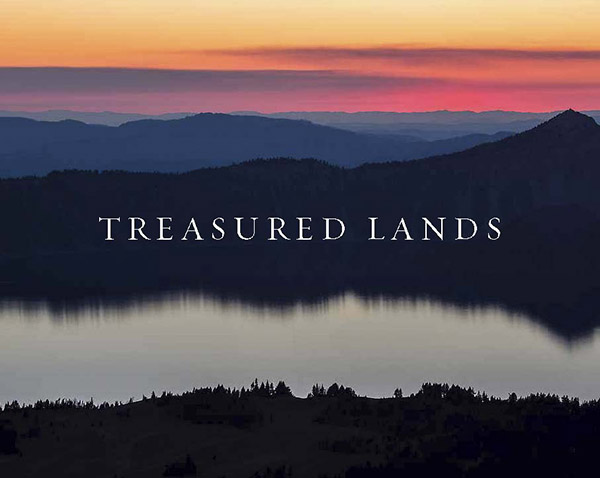

Treasured Lands Book Introduction

No Comments

This is the full text of the introduction to my upcoming book

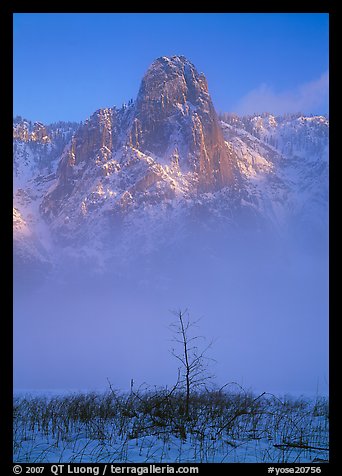

In February 1993, I visited Yosemite for the first time. It was love at first sight. That visit marks the start of my 20-year affair with the National Parks.

Growing up in France, mountaineering had provided me with my only experiences of wilderness. My time on the mountain was exhilarating and compelled me to adopt photography as a means to share with those who couldn’t see for themselves the beauty of the high peaks of the Alps. Eventually, I came to the United States for what was to be a short academic stay. I did not know much about the geography of this country, but I chose the University of California at Berkeley because I had heard from other climbers that nearby Yosemite had tall cliffs. At that time, I was not aware of the significance of the national parks, nor did I anticipate that they would change the course of my life.

Shortly after I arrived, the mountains beckoned and I headed to Alaska to climb Denali. The sheer scale and pristine beauty of the north far exceeded anything I had witnessed in the mountains of Europe. Later, I toured Death Valley. After standing on the highest point of North America, I was now looking at its lowest. I had never seen such wide-open spaces and deserts before, and the geological surprises concealed within this arid land mesmerized me. I realized how much diversity the national parks encompass—they present every ecosystem a vast continent has to offer, and it was all new to me.

Exactly a century ago, in National Park Portfolio (1916), the first-ever photography book about the national parks, Stephen Mather wrote: “Each park will be found to be highly individual. The whole will be a revelation.” Those few words summarize perfectly what fascinated me so much about the parks and motivated me to visit more of them. Each park represents a unique environment, yet collectively they are all are interrelated, interconnected like a giant jigsaw puzzle.

Not far from where I lived on the West Coast, Ansel Adams and others had established a rich tradition of American landscape photography. Wanting to approach my craft from the level of the prints I had admired in local museums and galleries, I learned to use a large-format camera in the summer of 1993. After I returned from Death Valley and inspected one of my first 5×7-inch transparencies on a light table, I was astonished to see more details than I noticed when I was standing at the scene. I realized that a viewer could have a close look at the landscape through the visually complex, detail-laden images, which would enable them to vicariously stand where I stood when I took the photo.

This notion inspired me to embark on a project that I thought was both original and compelling: photograph each of America’s national parks with a large-format camera, because only large-format photography would do justice to the grandeur of the parks. To pursue this, I settled in the San Francisco Bay Area and eventually left my career as a computer scientist to become a full-time photographer. By the summer of 2002, I had photographed the then 58 national parks. Each national park, even the ones close to one another, provided a unique experience, not only because of the diversity of their environments but also because of the ways in which one must explore them. While my outdoor proficiency was rooted in mountaineering, I had to learn the skills dictated by each park’s terrain, from scuba diving to kayaking to canyoneering. In order to find new ways of photographing the landscape, such as shooting the starry sky at night, I also added one of the first full-frame digital cameras to my kit. It entirely replaced the 35mm film camera that I carried to capture images unsuitable for large-format photography, but did not change my commitment to truthfulness and clarity. My quest to visit each national park was a twenty-year odyssey filled with the excitement commensurate with venturing—often alone—into the wilderness.

Traveling to many corners of the world has only increased my appreciation for our national parks and confirmed that they are the greatest treasures of the nation. One may think that their status guarantees that they will be preserved and protected for future generations, but that’s not a given. Even as the National Park Service celebrates its centennial this year, the agency faces a staggering budget deficit. Its mission can be successful only as long as citizens care about the land, which is often brought about by a personal connection attained through a visit that raises awareness. Exploring the national parks has brought me much joy, and the act of photography was an extension of that love, a desire to share with others in a tangible way the elation that comes with being in such special places. I measure its success by how much these photographs inspire viewers to visit the places for themselves, for the happiness they will bring through a deep connection with nature, and because the experience is likely to transform them into advocates for conservation. Most photographers understand that there is nothing more important than respecting the environment we seek to capture so that future generations will find it as beautiful as we did.

The Organic Act of 1916, which created the National Park Service, set forth two goals: to conserve the natural scenery and to provide for the enjoyment of these lands for future generations. The agency has done an outstanding job at meeting both of these objectives, although they can be contradictory. I am eternally grateful to those who set these treasured lands apart and to the men and women who protect them while making them approachable. During my long journey, I felt privileged to be able to experience such accessible yet untouched wilderness, a truly rare combination. If my photographs inspire viewers to visit these areas, the National Park Service has made it possible.

My hope is that this book will not only inspire you to go out and discover new places but also provide you with enough information for you to stand at the places where the photographs originated. You will see that even in the most crowded locations, even Yellowstone’s Old Faithful, it is possible to have an uncommon and solitary experience. Iconic attractions deserve a visit, but the parks are full of surprises as well—especially if you are willing to venture off the beaten path. This book pays as much attention to the lesser-known gems, such as California’s Lassen Volcanic National Park, as it does to the well-known parks, and within each park, it covers many corners, some quite obscure.

Also included are notes on photography for those who like to capture the moment or simply want to understand how the photographs were made. Photography has the power to help you connect with nature and with yourself. The pursuit of photography can give you the motivation to immerse yourself in the national parks and lead you to experiences that you may not have had otherwise. This could mean venturing northward to the Arctic Circle in winter to see the northern lights or venturing out of the lodge on a rainy day, where the luminosity of the forest in rainfall will astound you. While looking for a terrestrial shape to frame the Milky Way, you may enjoy the quiet solitude of the park trail at night, normally bustling by day. Even if you are a night owl like me, the anticipation of a sunrise might persuade you to get out of bed at 4 AM and hike to an overlook. And when the cosmic event eventually unfolds, you will be lost in the moment, subject to an intense concentration, free from the distractions of everyday life. Few activities, save for perhaps technical climbing, have brought me the same sense of focus and flow. In that state of heightened awareness, the world reveals more of its wonders to you—the more you look, the more you will see. While the natural beauty of the national parks is unmistakable, photographing it enables you make observations you may have otherwise missed.

My odyssey through the national parks has been ostensibly driven by the desire to make photographs, but my primary motivation was to explore and engage with the earth. The journey is the destination, but the photograph you take away from that destination has the power to inspire others to embark on their own journey. I hope that this book will do that for you.

To enter a drawing to win a free signed copy, visit treasuredlandsbook.com